Duke of Auerstaedt, Prince of Eckmühl

Pronunciation:

Louis-Nicolas d'Avoust (also spelled Davout) was born on May 10, 1770 in Annoux, into one of the most illustrious families in Burgundy. As such, he entered the Ecole militaire de Paris (Military College of Paris) in 1785 as a gentleman-cadet. This was the same institution from which Napoleon Bonaparte had just graduated.

In 1788, he became a Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal-Champagne cavalry regiment where his father, uncle and grandfather had previously served. From the beginning of the Revolution, Davout was a fervent proponent of republican ideals. However, his superiors did not share his enthusiasm. Instead, they convicted the over-zealous patriot and sent him to prison for inciting mutiny among the soldiers in his regiment. Released soon after, Davout resigned from the French Army in order to join a regiment of volunteers from Yonne (a French department) who elected him Lieutenant Colonel a week after arriving (September 22, 1791).

From 1792 to 1793, Davout fought in the North and in Belgium under Charles-François Dumouriez. At Neerwinden on March 18, 1793, he tried in vain to stop his superior from defecting to the enemy by ordering the men in his battalion to fire on the traitor. His career continued in the Vendée (a French department). In July, at the age of 23, he was successively promoted to Brigadier General and then to général de division (Major General). According to some, he refused this promotion and resigned due to a decree that barred officers of noble birth from the army. According to others, he was relieved from his duties by the same decree, though it could also have been due to the correspondence between his mother and members of the exiled nobility.

After 9 Thermidor and the fall of Maximilien Robespierre (July 27, 1794 in the French Republican Calendar), Louis-Nicolas Davout was able to rejoin the army and was sent to the Army of the Rhine as a Brigadier General. He soon became friends with his commander, Louis Desaix.

In September 1795, Davout captured Mannheim; though he was forced to capitulate two months later and was taken prisoner on November 22. After being quickly exchanged, he continued to fight along the Rhine in the two years that followed. He fought at Haslach (July 14, 1796) and at the crossing of the Rhine (April 18, 1797). On April 21, he seized a coach belonging to Baron Klinglin, the head of the Prince of Condé's secret service, containing the correspondence between General Pichegru and several exiled French aristocrats.

On Desaix's recommendation, Napoleon Bonaparte agreed to send Davout to Egypt, although he had initially been put off by the Brigadier General's unfriendly personality. In Egypt, Louis-Nicolas commanded a cavalry brigade that he led into numerous battles during the campaign (the Pyramids, Luxor, Abukir). He left Egypt with Desaix on March 3, 1800 following the Convention of Al-Arish.

He arrived in Toulon on May 6, after having been held by the English for a month in Livorno, and was promoted to général de division (Major General) on July 3 at the head of the cavalry in the Army of Italy.

On November 12, 1801, Louis-Nicolas Davout married Louise Leclerc, the sister of General Charles Leclerc who was brother-in-law to the First Consul. This alliance allowed him to enter the family circle of Napoleon Bonaparte. Having forgotten his unfavourable first impression, Napoleon named Davout Commander of the Grenadiers of the Consular Guard in 1802 and Marshal on May 19, 1804 as well as Colonel General of the Grenadiers in the service of the Imperial Guard.

The following year, Davout commanded the right flank of the French Army at Austerlitz contributing to a decisive French victory.

In 1806, Davout won the Battle of Auerstaedt with three divisions against a much larger Prussian Army leading to another French victory at Jena. On October 25, he entered Berlin two days before the Emperor and continued to win battles in Poland, Czarnowo and Golymin. He commanded the right flank for a second time at Eylau. He was rewarded for these successes as Governor General of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw (July 15, 1807) and with the title of Duc d'Auerstaedt (Duke of Auerstaedt) on March 28, 1808.

Davout left Warsaw on September 6, 1808 after nearly a year of conflict with the semblance of a Polish government established by the Treaty of Tilsit, though he benefited from the people's sympathy. He moved the Third Corps that he had commanded since 1805 to Silesia. After the dissolution of the Grande Armée on October 12, 1808, of which his Corps had been a part, he took command of the Rhine Army that brought together all French forces stationed in Germany.

He participated in the Second German Campaign in command of the Third Corps of the Grande Armée. On April 22, 1809, he distinguished himself at Eckmühl. On May 22, the destruction of the bridge across the Danube prevented him from joining the Battle of Aspern-Essling and on July 6 he decided the outcome of the Battle of Wagram. Marshal Davout became the Prince d'Eckmühl on August 15 following these exploits.

On July 1, 1810, Napoleon I named him Commander in Chief of the Army of Germany. In this role, Davout was specifically tasked with securing the North of the country and its major ports against trade with England as ordered by the Emperor. The Marshal executed his instructions with singular determination. He also rigorously prepared for the invasion of Russia.

At midnight on June 23, 1812, Davout launched the offensive by crossing the Neman River. Commanding the First Corps of the new Grande Armée, Davout had at his disposal five infantry divisions and two cavalry brigades totaling 67 000 men. Living up to his reputation, he enforced a strict adherence to military discipline and order.

However, the Russian Campaign spelled trouble and humiliation for Davout. Napoleon I began to rely less and less on his advice leading to the indecisive outcome of the Battle of Borodino (where Davout was injured) and presaging the disastrous French retreat. In the arguments that opposed the Marshal with his colleagues, the Emperor repeatedly sided against Davout especially in the case of Joachim Murat who the Prince d'Eckmühl despised. (On several occasions, Davout refused to support the King of Naples' troupes accusing the King of shameless self-promotion in battle. A dual between the two men was only avoided by the intervention of Napoleon I). Depressed and embittered after the particularly difficult retreat from Russia, Davout wrote to his wife, I most likely walked four fifths of the way back from Moscow.

Nonetheless, he defended Dresden with valour from March 9 to 19, 1813 after which he took command of the 32nd Military Division, including the Hanseatic departments in Germany which he had previously governed in 1810. Having received particularly harsh orders from Napoleon with regard to Hamburg, Davout implemented them without mercy, though this only antagonized the population. When hostilities resumed in August, he held the city until May 27, 1814, more than a month after the abdication of Napoleon I. He remained a French General under the direct orders of Louis XVIII.

When he returned to Paris, the new War Minister, Pierre Dupont de l'Etang, received Davout. Dupont de l'Etang informed the Marshal that the King had barred him from remaining in Paris and asked him to justify his conduct during the siege of Hamburg. Davout had to defend himself against three charges: firing on his besiegers in April 1814 even though they were flying the white flag of the Kings of France, looting the gold from the Bank of Hamburg, and committing arbitrary acts of violence (including numerous executions) to the disgrace of the French nation. His written report ignored, Davout convinced first Nicolas-Charles Oudinot and then Jean-de-Dieu Soult to intervene on his behalf, though neither were received by the King. The Marshal left the capital and took refuge in his estates, the Castle of Savigny .

He returned with Napoleon. The day the Emperor entered to Paris (March 20, 1815), Davout was already in the Tuileries Palace. After having first refused the post of Minister of War citing his character flaws, Davout allowed himself to be convinced by Napoleon and undertook to rebuild France's much-weakened war machine. (I believe [...] I am acting in concert with my father-in-law, the Emperor of Austria... in reality, he is finished and I am alone against Europe. You see my situation. Would you abandon me?

) During the Hundred Days he showed himself to be a tireless supporter and an excellent organizer.

The Emperor rejoined his army on June 12, leaving Louis-Nicolas Davout as Commander in Chief of the forces stationed around Paris. After Waterloo, the Minister of War sought first to persuade a distraught Napoleon I to continue fighting. All the same, after the abdication it fell to Davout to ask Napoleon to leave the capital though he had tried to avoid this task. Following a stormy meeting, the two men parted ways without emotion.

After the signing of the Saint-Cloud Military Convention on July 3, Davout resigned from the cabinet (July 6) and returned with his army to the Loire region as required by the treaty. Three weeks later, he passed command of his troupes to Etienne Macdonald who was ordered by the King to dismiss them. Davout once again sought refuge in Savigny.

Called as a witness during the trail of Marshal Ney, he declared that while he was a signatory of the Convention of July 3, 1815 governing the details of the capitulation, he would never have signed the document if he had not felt the need to conceal in his heart all those who had taken part in the Hundred Days. Louis XVIII was so displeased by this speech that he stripped Davout of his titles and placed him under house arrest in Louviers. The Prince of Eckmühl was left destitute since he could not access his assets held in countries no longer controlled by France. The sanctions against him were finally lifted after 18 months. His marshalate was restored on August 27, 1817 and he entered the Chamber of Peers on March 5, 1819.

He died in Paris of consumption on June 1, 1823. He is buried in the 28th division of the Père Lachaise Cemetery .

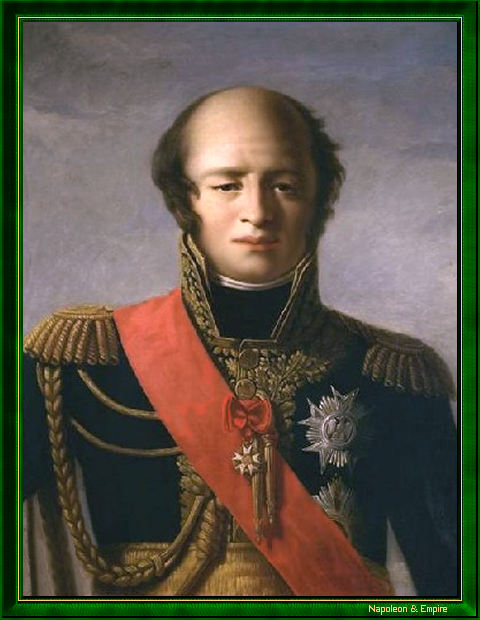

"Marshal Davout, Duke of Auerstaedt, Prince of Eckmühl" by Tito Marzocchi de Belluci (Florence 1800 - Paris 1871), after Pierre-Claude Gautherot (aka Claude Gautherot, Paris 1769 - Paris 1825).

Davout was Napoleon's only unbeaten Marshal.

At the time, Napoleon did not realize the importance of the Battle of Auerstaedt. When Davout's aide-de-camp announced the enemy's losses, the Emperor ironically responded, Your myopic Marshal

[Davout had very bad sight and wore glasses] was seeing double yesterday.

The fifth bulletin of the Grand Armée dated October 15 (after the two battles) failed to mention Auerstaedt.

Marshal Davout's difficult personality is reflected in the unflattering portrait of him painted by his colleagues in their memoirs. It seems he did everything in his power to make enemies out of his subordinates. According to them, he was distrustful, hard to please, and authoritarian. He organized a system of espionage that included his entire staff. He was often brutal and offensive in his remarks and routinely formed spiteful opinions of those around him that he refused to alter. Though even his most scathing critics had to recognize his complete integrity in financial matters, his great concern for the troupes and his almost fanatical sense of duty. At the same time, he was a devoted husband and father: To the end, he was above all paternal to the soldiers, fair to the non-commissioned officers, [...] but severe to his own officers.

The name "Davoust" can be found on the 13rd column (east side) of the Arc de Triomphe .

Acknowledgements

Other portraits

Enlarge

"Marshal Davout, Duke of Auerstaedt, Prince of Eckmühl" by Pierre Gautherot (1769-1825).

Enlarge

"Marshal Davout". Nineteenth century engraving.

Enlarge

"Louis-Nicolas Davout in 1792" by Alexis Nicolas Pérignon the younger (1785-1864).

Enlarge

"Marshal Davout, Duke of Auerstaedt, Prince of Eckmühl" by Tito Marzocchi de Belluchi (1800-1871).

Enlarge

"Marshal Davout", engraving by Amédée Maulet (1810-1835).