Date and place

- October 14th, 1806 northwest of Jena, between Weimar and Leipzig (nowadays Thuringia, Germany).

Involved forces

- French army (54,000 men) under Emperor Napoleon I.

- Prussian army (55,000 men) under General Friedrich Ludwig Fürst zu Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen.

Casualties and losses

- French army: between 4,000 and 7,500 soldier killed or injured.

- Prussian army: 12,000 dead or wounded, 15,000 prisoners, 30 to 40 flags, all the artillery.

Aerial panorama of Jena battlefield

The victory at Jena, combined with that of Auerstaedt, obtained the same day by Marshal Davout, resulted in the near destruction of the Prussian army and the collapse of all resistance in the country. This unexpected catastrophe would be paid for, when peace returned, by a drastic reduction in the area of the Kingdom of Prussia.

Overall situation

Pushed by the violent anti-French party which was dominating the Prussian court under the impulse of Queen Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, King Frederick William III transmitted to France, October 1, 1806 (Napoleon will only get to know about it on the 7th), an ultimatum enjoining him to withdraw his troops from the right bank of the Rhine before the 8th.

The response was immediate and rapid. Napoleon, who was then in Bamberg, opened the hostilities on October 8 and took the road to the Frankenwald with the Grande Armée, of about 180,000 men. The army went north through Thuringia, heading towards Leipzig in three parallel columns, ready to response in any direction, depending on where the danger is coming from.

On October 10, in Saalfeld, a first engagement saw the victory of Jean Lannes against the Prussian vanguard commanded by Prince Louis-Ferdinand of Prussia , who died on the battlefield.

The speed of the maneuver totally surprised the Prussians while en route to the Rhine. Their army, about 130,000 strong, was still living in the memory of its past glory, the illusion of its superiority and the contempt of its future adversary. It was however commanded by a man who has already experienced defeat against the French, the defeated in Valmy Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (known in France under the name of "Duke of Brunswick") .

Once the enemy’s left got overwhelmed, Napoleon tried to exploit this advantage by sending the bodies of Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte and Louis-Nicolas Davout toward the west, in the hope of cutting the enemy from his capital, Berlin. With the rest of his troops, the Emperor marched on Jena:

Realizing the danger, the Prussian command changed its plans and the direction of its troops. Brunswick, with about 70,000 men, headed northeast, leaving Prince Friedrich Ludwig zu Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen to protect his retirement with 50,000 soldiers.

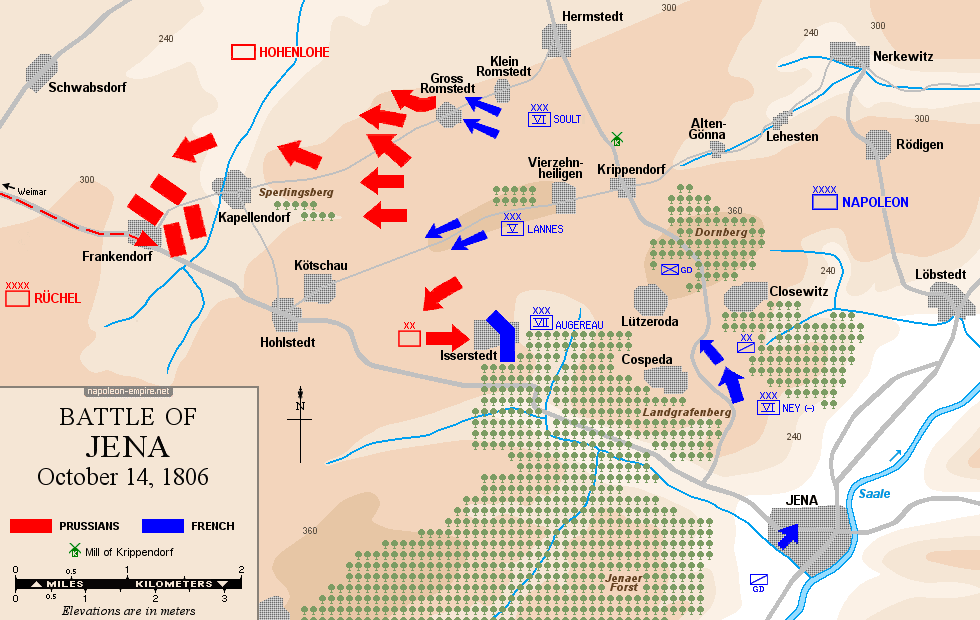

Position of the troops

Prussians

On the night of October 13th to 14th, the various detachments under Hohenlohe's orders were organized as follows:

- Bogislav Friedrich Emanuel von Tauentzien was occupying the Lützeroda-Closewitz line.

- Ernst Friedrich Wilhelm Philipp von Rüchel was west of Weimar, about twenty kilometers away from the future battlefield.

- Julius von Grawert was camping not far from Kapellendorf, oriented towards the south.

- The Saxon brigade of Ludwig Ferdinand von Dyherrn (and not Rudolf Gottlieb von Dyherrn, often quoted, who died in July 1806) was on his left, that of Heinrich von Cerrini di Monte Varchi near Kötschau

- The Saxon division of Niesemeuschel was stationned south of Isserstedt.

- The Prussian cavalry was standing near Grossromstedt.

- Friedrich Jacob von Holtzendorff, with 4 to 5,000 men, was guarding both the Dornburg and Camburg bridges.

The whole represented about 55,000 men, equipped with 120 guns.

French

All the forces at the disposal of the Emperor were totaling about 65,000 men, armed with 173 guns, but a good part of them were not going to be available during all or some part of the battle. The different French corps were placed as follow:

- Jean Lannes on the eastern part of Landgrafenberg, where the enemy could not see him.

- The foot guard, under the command of François-Joseph Lefebvre, was behind him.

- Charles Augereau was stationed south-west of Jena, towards Lichtenahain.

- Jean-de-Dieu Soult had a division at Jena, the other two were en route and were going to reach the battlefield the next day around noon.

- Michel Ney and his vanguard (Auguste François-Marie de Colbert-Chabanais 's cavalry, two elite battalions and six guns) were also in Jena.

- Heavy cavalry (Dominique-Louis-Antoine Klein , Jean-Joseph Ange d'Hautpoul, Etienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty ) were going to arrive only in the course of the day of the 14th.

The rest of the army was not going to take part in the fighting.

Prelude to the battle.

On October 13th, various information confirmed to Napoleon that the Prussian army was in retreat towards Weimar, before turning to Berlin. His own troops were following a north-northeast line at that time, he made them slightly deviate on their left in order to attack the flank of the enemy.

His plan called for a main battle on October 16th because he did not know that Brunswick, in withdrawing, left Hohenlohe behind him in Jena . By clashing with the latter, it was therefore with the whole Prussian army that the Emperor thought he was dealing with.

On the night from the 13th to the 14th, Napoleon made the 20,000 men in Lannes corps climb the slopes of the Landgrafenberg , which the Prussians deemed to be impracticable and left unguarded for this reason.

The V corps then advanced on the Windknollen plateau and its windmill. Behind him came the artillery and the 5,000 men of the Imperial Guard. The latter settled around the headquarters, built on the heights, in a place known today as the Napoleonstein [50.94512, 11.57144].

On the morning of the 14th, Napoleon did not intend to make a decisive blow to his opponents. The orders he gave then were only intended to deploy his troops in the plain, waiting to make the appropriate decisions according to how the enemy would react.

The narrowness of the space in which his soldiers were then confined exposed them to complete destruction if an attack was meant to surprise them. The limited commitment initially envisaged, however, was going to gradually evolve into a pitched battle.

The fights

First hours: the fight against Tauentzien

The heavy fog that was drowning the site delayed the start of operations until six in the morning. At this moment, in spite of the darkness which was still reigning, the Emperor gave the order to advance.

Lannes took the the lead. His V Corps took the direction of Closewitz : first the various brigades of the division of Louis-Gabriel Suchet - that of Michel Marie Claparède in two lines separated by two guns, followed by that of Honoré Charles Reille , finally that of Dominique Honoré Antoine Vedel which served as a reserve - then, on the left and slightly behind, the division of Honoré Théodore Maxime Gazan .

Unable to distinguish their targets, the troops relied on the slope to advance and arrived without realizing it on the enemy outposts established at the edge of the wood of Closewitz. A sustained shooting ensued for more than an hour before Suchet managed to seize the wood once the fog was up. The Prussians retreated to the village, of which they were soon also chased from.

Around eight o'clock, Suchet, who was then marching towards Krippendorf , suffered an attack on his left flank by the Saxon grenadiers of the Cerrini brigade. Supported by troops from Gazan's division, he threw them back beyond Lützeroda and the Krippendorf ravine, taking their twenty-two guns.

General Tauentzien, having somewhat neglected the defense of the villages of Closewitz and Lützeroda, was determined to defend the Dornberg . But, while concentrating his troops there, an order from Hohenlohe commanded him to retreat to Kleinromstedt (four kilometers to the northwest).

He then withdrew from his position – which fell immediately to the hands of Lannes – and settled north of Vierzehnheiligen, with the exception of some detachments left in the village and the mill of Krippendorf [50.98035, 11.54725]. Four battalions of Saxons who had just joined him and a battery were positioned by his care on the slopes to the south of this village. It was about 9:30.

The French battle line strengthened

Meanwhile, the rest of the French lines started moving. As soon as Lannes' offensive left him the opportunity, Ney, accompanied only by his vanguard, crossed the Landgrafenberg to tumble between Krippendorf and the wood of Isserstedt at around 9:15 am. Ney was then along Lannes’ left side and soon saw Augereau coming to his and to part of his VII Corps.

At about 10 o'clock, after leaving their bivouacs at Lichtenhain with the sound of the cannon, it was difficult to cross the crowded Mühlthal and cross the Cospedaer Grund – or bypass it when the roads were too difficult – the divisions of Jacques Desjardin then that of Étienne Heudelet de Bierre , and finally the cavalry of Antoine Jean Auguste Durosnel were going to begin settling their lines facing the Wood of Isserstedt .

Soult chased Holtzendorff

Soult, with the available troops from the IV corps, the division of Louis Vincent the Blond of Saint-Hilaire and the two brigades of light cavalry of Etienne Guyot and Pierre Margaron , had just started attacking the extreme left of Tauentzien. Bypassing the Landgrafenberg from the east, he pushed back to Krippendorf the Saxons settled in the woods of Zwätzen and Closewitz and then took up a position on a height in front of Lehesten .

There, he clashed with General Holtzendorff, who had left Naumburg at the sound of the cannon and was preparing to repel the French, whom he suddenly saw ahead of him, around Rödigen . The Prussian general succeeded at first but then underwent the assault on Saint-Hilaire which forced him to retrograde.

Holtzendorff's cavalry, supposed to cover this retreat, surrendered way too quickly to the charges of Guyot's hussars and Margaron's hunters, and disbanded. His disorderly flight led to confusion in the Prussian infantry. Holtzendorff got reduced to hastily retreat to Nerkewitz - where Soult stopped pursuing him - and then to Stobra and Apolda when he saw Bernadotte's vanguard emerging before him.

The IV corps, for its part, having the order to always stand at the right of the army, left to to Altengönna .

The front changed his direction.

At that time, and without any order commanding it, the orientation of the front swung from north to west - and thus the French left - in favor of the pursuit of Tauentzien's troops. In this new position, the imperial army was facing the village and mill of Krippendorf to its right, Vierzehnheiligen in front of his center, the wood of Isserstedt and the village of the same name in front of his left and extreme left.

Once again, the Suchet division took the first offensive. Claparède quickly seized the mill and the village of Krippendorf and began climbed the plateau behind it.

Napoleon, who had just been brought to the front line, sent the artillery of the Guards and one of the regiments of the Reille Brigade to the assault on Vierzehnheiligen . The four Saxon battalions, initially repressed, clanged valiantly to the village itself and managed to repel the assault. Tauentzien took the opportunity to counterattack and take over Krippendorf and his mill.

As he was lacking information on the fighting that was happening in his back, Soult against Holtzendorff, a fight from which he only heard the sound of the gun without knowing if the marshal had the upper hand, Napoleon took the decision to stop Lannes who was preparing an assault on Vierzehnheiligen.

He also sent the Vedel Brigade into observation in the direction of Lehesten and ordered the Desjardins Division, of the 7th Corps, to accelerate its movement. It was approximately 10 :30.

Hohenlohe’s intervention

Shortly before, Hohenlohe, the Prussian general-in-chief, perfectly inert since the beginning of the fighting despite the rumbling of the artillery fire which reached him in his Kapellendorf headquarters and the requests for orders of his generals, had finally decided to take action.

Long convinced that the day would not see any major fight, to the point of suspending the movements ordered by his subordinates, he ended up going against this by listening to the report of General Grawert. He then wrote to General Rüchel, who was encamped near Weimar, to ask him for reinforcements, ordered Tauentzien to retreat to Kleinromstedt, and advanced himself to Vierzehnheiligen.

He arrived within range of the gun at the very moment when Napoleon interrupted his offensive while awaiting news of Soult. Hohenlohe, likewise, stopped. As Tauentzien, seeing his chief arriving, evacuated the village as he had been ordered, the village is suddenly empty.

In a rather incomprehensible way, Hohenlohe neglected to occupy it and preferred to frame it with two large masses of cavalry, one of them equipped with light artillery. For a few moments, the battle was reduced to exchanges of shots and bullets around Vierzehnheiligen.

An inspiration from Ney was going to revive it. It was beyond Lützeroda. Although he still had only two elite battalions with him and the light cavalry of Colbert-Chabanais, he decided on his own initiative to occupy the land between Vierzehnheiligen and the little wood of Holschen .

He clashed violently with the masses of cavalry brought by Hohenlohe. Prussian dragons and cuirassiers cut the French hussars into pieces and pushed them back to the elite battalions. But the firm countenance of these, formed in squares, dissuaded the enemy from confronting them.

On the contrary, Ney attempted a second attack to prevent any offensive return from the enemy. This new movement, carried out without the order of the Emperor, probably irritated this one, who thought it had to support him. The cavalry brigade of Anne-François-Charles Treilhard , of the V Corps, got sent to Ney’s rescue while two regiments of Divisions Suchet and Gazan were launched to attack Vierzehnheiligen.

Hohenlohe's inertia, which kept his troops several hundred meters behind the objectives of this offensive, offered, at first, easy success to the French. Ney, supported by the regiments of the 5th Corps, seized Vierzehnheiligen without a fight, then mastered the surrounding woods , crossed the Isserstedt and set up a detachment in the village of the same name.

Prussian counter-attack

The Prussian general-in-chief then decided to take back what he had done nothing to protect. He advanced, with 22 battalions of infantry and 38 squadrons of cavalry, on a front stretching from Vierzehnheiligen on the left to Isserstedt on the right. The progress was made with the regularity and coolness that made the reputation of the Prussian infantry in the previous century. Isserstedt got taken again, then the woods.

The Prussian right overflew Vierzehnheiligen in the north while the center approached the village. The Prussian command began to dream of victory but failed to emancipate itself from its old habits.

Instead of suddenly throwing all its forces, infantrymen and cavalrymen, at a specific point of the enemy apparatus and thus to make a decisive blow to it, he stopped his battalions within a rifle distance of the village and made them methodically execute a platoon fire that the reinforcement of a gun battery made noisier but hardly more effective.

The French skirmishers, well hidden behind the hedges and fences, suffered without great losses the shots of an enemy who, on the contrary, exposed himself to their fire. The artillery, which the Emperor had brought from the Dornberg, aggravated the ordeal of the Prussian troops. The losses were such that one of their regiments, forgetting the discipline, abandonned its position and had to be brought back by force by its officers.

While the Prussian infantry was exposed to gunshots, the French troops continued to arrive on the battlefield, without the slightest suspicion from the enemy command.

A new attempt by Lannes north of Vierzehnheiligen was repulsed by their cavalry, Hohenlohe and his staff, who only saw Frenchmen in retreat or, for those entrenched in the village, beginning to slow down the rate of their shots, already believing themselves victorious. But, again, the lack of audacity of the German generals hampered their movements. A bayonet charged on Vierzehnheiligen, which was a strategy considered for a moment, got judged by their leader, General Grawert, too demanding for troops that a long station under enemy fire had demoralized and weakened.

Contrary to the recommendations of his chief of staff Christian Karl August Ludwig von Massenbach, Hohenlohe agreed and decided to wait for the arrival of Rüchel's men to launch a larger attack.

Napoleon, too, was waiting. He had only about thirty thousand operational men (the V Lannes corps, the brigades of Pierre Belon Lapisse and Nicolas Conroux of the VII, the elite battalions of Ney, and the Guard on foot) and still thought he had the bulk of the Prussian army in front of him. Moreover, he knew that the concentration of his troops was in progress. The time had not yet come to fully engage.

Therefore, until early afternoon, the two opponents only engaged their first lines in the battle, while delaying the decisive commitment while waiting for their backings.

French offensive

But those of the French were much closer. About an hour and a quarter, Soult, after having repulsed Holtzendorff's corps beyond Nerkewitz, came to the north of Krippendorf, in the prolongation of the right of the imperial army. His arrival provoked a general and spontaneous movement towards the front of the whole first French line, from Krippendorf to Isserstedt.

Napoleon, who had also just got informed of the arrival of the division of Jean Gabriel Marchand and Gaspard Amédée Gardanne of the IV Corps, the Heudelet division of the VII, the heavy cavalry of Klein (dragoons) and Hautpoul (cuirassiers), commanded the charge. Joachim Murat took command of the riders. The infantry columns set out, supported by the artillery and light cavalry of the different corps.

The Prussian line, somewhat discouraged by almost two hours of exposure to the French fire, surrendered. The Desjardins Division and the Vedel Brigade took Isserstedt and pushed the Saxon-Prussian troops opposite to the northwest and west.

Hohenlohe tried to resist Lannes around Vierzehnheiligen but some of his troops flanked. Cut off from his right, threatened to be overwhelmed on his left by Soult, he managed to retreat in good order on Kleinromstedt where Tauentzien was collecting the remains of his army corps.

Once there, the Prussian general-in-chief also encountered the Cerrini brigade and tried, with all these forces together, to hold this new position. But his troops were no longer able to suffer the simultaneous attacks of Lannes, a division of Soult, and the cavalry of Murat.

The Grawert division was the first to flex and then to disband. His escape was initially protected by the resistance of Cerrini and Tauentzien but they yielded in turn and the Prussian army was soon a crowd of fugitives who were hurrying towards Obensdorf and Grossromstedt:

Ruchel arrival and rout

The French troops hunted them without encountering resistance beyond Grossromstedt, in the valley of Kapellendorf, where they collided, on the Sperlingsberg , with a new Prussian contingent which had not yet been engaged in battle.

This was the Rüchel Corps who finally arrived to the rescue. However, the latter, with its 26 battalions and 28 squadrons (about 15,000 men) opted for the offensive rather than taking a defensive position and offer the remains of his army a shelter behind which to rally.

He left a quarter of his force in reserve and, at about 14 hours, walked forward with the remainder, the infantry in the center, the cavalry on both wings. The maneuver seemed at first successful.

The Prussian infantry, advancing in perfect order, repulsed the tirailleurs of Lannes beyond Grossromstedt and even took some guns; the cavalry, on the left wing, obtained the same success against the imperial cavalry (reserve dragons, hussars and chasseurs Soult) before colliding with the division Saint-Hilaire who managed to break his impulse.

But Rüchel's corps then found itself facing all the French forces. Lannes and a part of Ney's body were facing him; Soult was on his right, reinforced by a brigade of Klein's dragons; on his left stood the rest of Ney's forces, those of Augereau, and Murat commanding all the cavalry (light cavalry of the corps of Lannes, Ney and Augereau, 2nd brigade of the Klein dragons, and cuirassiers of Hautpoul).

The fight went down the line. Half an hour later, the Prussian resistance was finally broken and the fugitives were rejected in the ravine of Kapellendorf.

Exploitation

The unrelenting pursuit was conducted by the Saint-Hilaire, Marchand, Desjardins, Heudelet and Vedel Brigades divisions, supported by light cavalry, Klein's dragoons and Hautpoul's cuirassiers, and five artillery pieces on horseback from Lannes corps.

Of all the Prussian army, only the Saxon corps commanded by Hans Gottlob von Zezschwitz, strong of 10,000 men, was still able to fight. Positioned in the morning on a hill at the exit of Muhlthal, at a place called Schnecke, it had not moved since. Circumstances had kept Zezschwitz out of the fighting and no order to retreat had come down to him. He was therefore cut off from the Prussians.

Napoleon, on learning of his existence, sent against him the divisions Marchand and Heudelet, not wishing to let a troop in such good condition, free, behind his left wing. The attack occured around 15 hours. Overwhelmed by the number of their adversaries, assaulted on all sides, the Saxons, after a good resistance, disbanded and joined the great wave of fugitives that was flowing to the Ilm.

Arrived near Weimar, Prince Hohenlohe rallied a few thousand men with whom he hoped to protect the retreat from the rest. But this thin cordon of troops only resisted for a moment the charge of the French. The prince was wounded, and his men were running in the streets of the city. At 4 p.m., the battle was over.

In the evening , Lannes was in Umpferstedt, Soult a little further north, Ulrichshalben, Murat and Ney in Weimar, Augereau beyond this city.

The French lost between 4,000 and 7,500 men, the Prussians 12,000, including General Rüchel wounded and fleeing, plus 15,000 prisoners, 30 to 40 flags and almost all their artillery.

Consequences of the battle

The consequences of the battle cannot be dissociated from those of the battle of Auerstaedt, which took place on the same day, and which saw the corps of Davout destroy that of Brunswick, and by the same the rest of the Prussian army.

These two defeats combined caused total discouragement of what remained of Prussian troops.

In the following days we saw fortresses being taken by a regiment of hussars. On October 27, three weeks after the start of the campaign, Napoleon entered Berlin through the Brandenburg Gate [Brandenburger Tor] . On the 28th, Hohenlohe and the survivors of his army met the Marshal Murat. On November 7, Blücher's capitulation offered Lübeck to the French. On the 8th, Ney obtained that of the Magdeburg garrison (which was going to evacuate the city only on the 11th), recovering 20,000 prisoners and several hundred guns.

An armistice was signed on November 30, which did not end the war. King Frederick William III, who then hoped for his salvation from the intervention of the Russians, was going to have to wait for their own defeat to know the consequences of his own. It was going to be the loss of half of its territory, 5 million inhabitants and almost all of its strongholds, with the payment of compensation of 120 million francs, colossal for the time. All conditions that he was going to be forced to accept by treaty to Tilsit, July 9, 1807.

In the longer term, the shock of this terrible defeat was going to be one of the distant causes of German unification. The humiliation felt, triggered both a wave of nationalism and the awareness of the need to unify and reform the country to prevent it from being renewed.

Map

Picture - "Napoleon reviewing his Imperial Guard at Jena". Painted 1836 by Emile Jean Horace Vernet.

The Emperor wrote the following official proclamation to announce in France the brilliant results of the campaign:

"One of the first military powers in Europe, who once dared to offer us a shameful capitulation, is annihilated."

"The forests, the defiles of Franconia, the Saale, the Elbe, we have passed through them in seven days, and in the meantime have fought four battles and a great battle; we have made sixty thousand prisoners, taken sixty-five flags among which those of the guards of the King of Prussia, six hundred pieces of cannon, three fortresses, more than twenty generals: but more than half of you regret not having drawn a gun shot. All the provinces of the Prussian monarchy up to the Oder are in our power."

For his part, the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), then Privat-docent at the University of Jena, far from sharing the anti-French fanaticism of some, wrote this as the Emperor entered his city: "Jena. Monday, October 13, 1806, the day when Jena was occupied by the French and where the Emperor Napoleon entered its walls. " "[...] I saw the Emperor - this soul of the world - come out of the city to go in gratitude; it is indeed a wonderful feeling to see such an individual who, concentrated here on one point, seated on a horse, spreads over the world and dominates [...] All this progress was only possible thanks to this extraordinary man, whom it is impossible not to admire [...] As I already did earlier, all wish good luck to the French army. "

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.