Date and place

- February 8, 1807 at Preußisch Eylau [now Bagrationovsk, Russia], 30 km southeast of Königsberg [Kaliningrad].

Involved forces

- French army (46,000 then 65,000 men), under the command of Emperor Napoleon 1st.

- Russian-Prussian coalition (75,000 then 84,000 men) commanded by Russian general Levin August von Bennigsen.

Casualties and losses

- French army: between 5,800 and 25,000 men, depending on the source, including a dozen generals.

- Russian-Prussian coalition: 20,000 to 30,000 men

The Battle of Eylau is often cited as one of the deadliest of the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon himself was affected by it. Moreover, this "butchery", marked by a monumental cavalry charge, perhaps the greatest in history, did not even prove decisive, to the point that each side claimed victory.

General situation

In autumn 1806, the Prussian army was so quickly defeated at Jena and Auerstaedt that its Russian allies had no time to come to its aid. The 60,000-strong corps sent by Tsar Alexander I under the command of Leonty Leontyevich Bennigsen (Levin August Gottlieb Theophil von Bennigsen - Леонтий Леонтьевич Беннигсен), had to wait for reinforcements to take on the Grande Armée.

These reinforcements arrived in December in the form of two contingents of 50,000 and 30,000 men respectively. The first was under the command of General Fyodor Fyodorovich Buksgevden (Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden - Фёдор Фёдорович Буксгевден) , while the second was made up of members of the Russian Imperial Guard.

Now in numerical superiority, the Russians went on the offensive in January 1807. The initial battles were unfavorable, however, allowing Napoleon to regain the initiative and undertake a maneuver designed to drive the enemy into the Baltic Sea .

Unfortunately for the French Emperor, his plans fell into the hands of the retreating enemy. To force Bennigsen into battle, Napoleon marched on Koenigsberg [Kaliningrad - Калининград], the key Russian position.

After several partial engagements, Bennigsen tried to stop him at Preußisch Eylau [Bagrationovsk - Багратионовск] [54.3867, 20.64070].

Preliminaries

Bennigsen arrived on the morning of February 7, 1807, and positioned his rearguard − some 15,000 men commanded by Pyotr Ivanovich Bagration (Пётр Иванович Багратионv) − to the southwest of the village, towards the Ziegelhof ponds . The French soon arrived. Napoleon set up camp on a hill to the east of the hamlet, from where he watched Jean-de-Dieu Soult's IV Corps attack well into the evening.

At 10 p.m., the Marshal himself captured the Preußisch Eylau cemetery. This would not be the last time the cemetery would be bitterly contested. The Russians, also battling Joachim Murat's cavalry and Charles Augereau's infantry, slowly retreated along the village streets , before finally being driven out.

In the hours that followed, in the middle of the night, they attempted a counter-attack. It was repulsed. All that remained was for them to set up camp on the plain north of Eylau, with a view to resuming the battle the following day.

Preparations

The Russian position

Bennigsen had around 75,000 men at his disposal, excluding Anton Wilhelm von L'Estocq's 9,000-strong Prussian corps, which would not arrive until the course of the battle. With his considerable numerical superiority, the Russian general-in-chief intended to fight on the wide open plain where he had bivouacked his troops, north of Preußisch Eylau.

The terrain there was favorable to cavalry action, as the following chapter would show, and also had the advantage, from his point of view, of providing easy communications with Königsberg, as well as a ready-made line of retreat in the direction of the river Pregel [Pregolya - Преголя] , should the need arise.

His army was arranged in two lines, close to each other. The left, to the southeast, stretched as far as Serpallen [Kaschtanowka - Каштановка − a village that no longer exists] , under generals Karl Fyodorovich Baggovut (Karl Gustav von Baggehufwudt - Карл Фёдорович Багговут) and Mikhail Bogdanovich Barclay de Tolly (Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly - Михаи́л Богда́нович Баркла́й-де-То́лли).

In the center were the Alexander Ivanovich Ostermann-Tolstoy (Александр Иванович Остерман-Толсто́й) , Fabian Wilhelmovich Osten-Sacken (Fabian Gottlieb von der Osten-Sacken - Фабиа́н Вильге́льмович О́стен-Са́кен) , Ivan Nikolaevich Essen (Magnus Gustav von Essen - Иван Николаевич Эссен) and Nikolay Alexeyevich Tuchkov (Никола́й Алексе́евич Тучко́в) divisions. The right, commanded by Yevgeni Ivanovich Markov (Евге́ний Ива́нович Ма́рков) , touched down at Schloditten, three kilometers north of Eylau, leaving a fairly large gap between it and Tuchkov, a gap occupied by Cossacks.

The reserve, made up of three divisions − Andrey Andreievich Somov (Андрей Андреевич Сомовы), Dmitry Sergeyevich Dokhturov (Дмитрий Сергеевич Дохтуров) and Nikolay Mikhailovich Kamensky (Никола́й Миха́йлович Каме́нский) − reinforced the center. Behind the latter, a reserve of 28 cavalry squadrons, commanded by Prince Dmitry Vladimirovich Golitsyn (Дми́трий Влади́мирович Голи́цын) , was piled up, while the rest of the cavalry, under Matvey Ivanovich Pahlen (Carl Magnus von der Pahlen - Матве́й Ива́нович Па́лен) , was ranged behind the Ostermann division, not far from Klein-Sausgarten [Bolschoje-Osjornoje - Большое Озёрное] [54.38383, 20.68844].

Finally, the artillery, numbering around 400 cannons and howitzers, was distributed along the entire front line, with its reserve also a little to the rear. The general-in-chief and his headquarters were located at Auklappen [Maloje Osjornoje - Малое Озёрное] [54.39737, 20.67093] , two and a half kilometers northeast of Preußisch Eylau (the name of this hamlet is sometimes incorrectly spelled Anklappen):

The French system

On the morning of the battle, the French position was not fully in place. Napoleon was waiting for Michel Ney, who had been ordered to rally as soon as possible, as the Emperor had initially had no intention of committing himself until he arrived. In the meantime, Soult and Augereau, the latter ill and unable to ride his horse, occupied the field.

Louis Vincent Le Blond de Saint-Hilaire was on the right (to the south-east) near Rothenen [a village that no longer exists, in Polish territory, a few hectometres from the border with the Kaliningrad oblast]; Claude-Juste-Alexandre Legrand hid this village; Jean François Leval was on the left, with the exception of one of his brigades guarding the cemetery. The space between this and the Saint-Hilaire division was occupied by Marshal Augereau's two divisions, reduced to around 10,000 men by the vicissitudes of the campaign.

Louis-Nicolas Davout, arriving via the Heilsberg [Lidzbark Warmiński] road, was on the march towards Serpallen but had not yet reached his position. In reserve, the Guard stood by the cemetery. Napoleon was nearby, on the low hill at the top of which sat the village church [54.38316, 20.64274] .

The cavalry spread out on both wings, on the left towards Althof [Orechowo - Орехово] (sometimes spelled Althoff) [54.42053, 20.60953], on the right behind the Saint-Hilaire division. A formidable reserve under Murat, with generals Emmanuel de Grouchy, Dominique-Louis-Antoine Klein and Jean Joseph Ange d'Hautpoul around him, was massed behind Augereau.

Including Davout and Ney, who were not yet on site, Napoleon had 65,000 men and 200 cannons.

The Russian plan

Bennigsen wanted to cut the French army in two, at Preußisch Eylau itself. To achieve this, he planned first to use his artillery and then to bring the efforts of his right wing to bear on the village. To accomplish uits mission, the right wing would be reinforced by L'Estocq's Prussian corps, expected to arrive via Althof.

The French plan

Napoleon, for his part, intended to begin by pinning down the enemy and wearing them down. Soult's corps and artillery would take charge. Davout, on the right, would then open up on the Russians' flank, while Augereau would force a passage between their center and left. Ney, on his arrival, would support the left wing, whose position would be a little adventurous until then.

The battle

First fights

The fighting began between 6 and 9 a.m. − witnesses disagree on this point. Initially, there was an exchange of artillery fire. The Russians pounded Rothenen, the cemetery and the village of Eylau, which was quickly set on fire. Although the cannonade was appalling, it was not totally effective. Many projectiles hit walls, or only troops in thin lines. Napoleon retaliated by using all his guns. The more deadly French fire, however, was met stoically by the Russian troops, who were oblivious to the havoc it wreaked on their lines.

Around nine o'clock, it seems, Bennigsen took the offensive. A brigade from Tuchkov's corps, on the Russian right wing, attacked the "Butte du Moulin". It was a failure. And while the French left retreated to Eylau, a counter-attack developed on the other wing. Augereau and Saint-Hilaire advanced on the enemy, bypassing the village. They headed for Serpallen. But as Davout had still not shown up, Napoleon did not insist.

Davout's arrival

The victor of Auerstaedt, however, was not long in coming. At around 10 a.m., his vanguard, commanded by Louis Friant , captured Serpallen before marching on Klein-Sausgarten, where Baggowut had retreated. Although caught by the Ostermann division and Russian cavalry, and then bombarded by artillery, Friant nevertheless continued his movement, while the Charles Antoine Morand division, behind him, moved into Serpallen.

Bennigsen's reserves moved towards Davout, who received support from Saint-Hilaire, while Augereau and his VII Corps were ordered to attack the enemy center. It was around noon.

Augereau's attack

Augereau's corps was made up of the two divisions of generals Jacques Desjardin (right) and Étienne Heudelet de Bierre (left). Saint-Hilaire, tasked with closing the gap between Augereau and Davout, extended their line and advanced in the same movement.

But, misled by a sudden snowstorm, the French troops, instead of making the intended slight left to approach the enemy line, exaggerated their change of direction and found themselves marching in front of the Russian front.

The Russians immediately seized the opportunity. A 72-gun battery crushed the VII Corps under its machine-gun fire. Decimated and totally disoriented, the latter left a gap between itself and Saint-Hilaire. The Russian cavalry took advantage of this to further overwhelm it. The survivors strayed into the enemy center before retrograding towards the Preußisch Eylau cemetery, on the way to which they had the misfortune of being cannoned by French batteries blinded by snow squalls.

In a quarter of an hour, Augereau lost half his strength: 5,000 men, killed or wounded, including the marshal himself and his two divisionnaires. We even saw an entire regiment, the 14th Line, destroyed on the butte [54.38702, 20.64871] where it had sought refuge, practically under the eyes of the Emperor, who sent several of his aides-de-camp to urge him to fall back, to no avail.

The disaster of the VII Corps left a large gap between the Morand and Saint-Hilaire divisions, which the Russians naturally tried to exploit. Bennigsen's infantry marched towards the cemetery where Napoleon was standing, accompanied only by a few battalions of his Guard. These were ordered to charge with bayonets, without firing.

A titanic white-knuckle fight ensued. For a moment, the threat to the Emperor's position seemed serious enough to some of the marshals that there was talk of evacuating him.

But Napoleon, who had been the first to realize that the enemy offensive would run out of steam before it reached him, was content to sit back and appreciate the audacity of the Russian troops (Imperial Guard, cavalry and Somov's division). Then, once their momentum had effectively run out in the face of the ardor of the grenadiers of Jean Marie Pierre Dorsenne and the chasseurs of Nicolas Dahlmann , he called Murat to him and ordered him to counter-attack.

The great cavalry charge

Murat's cavalry reserve was stationed behind the Eylau church, in the direction of the frozen, snow-covered ponds . A total of 58 squadrons. The Guard cavalry, which was also about to charge, was not formally under his orders, but those of Jean-Baptiste Bessières. That's ten more squadrons.

Murat ordered the troops in five lines: Grouchy's dragoons, Hautpoul's cuirassiers, Klein's dragoons, Jean-Baptiste Milhaud's dragoons, chasseurs and grenadiers de la Garde. The charge started from the right wing, near the present site of the L'Estocq monument [54.37937, 20.65156] .

Two initial charges were led by the two brigades of the Grouchy division. They failed to make a serious dent in the Russian line.

Murat then decided to bring all his forces to bear simultaneously. This time, the first Russian line was broken; the second was tumbled and fled behind the Auklappen wood, unmasking the third, which included Somov's infantry and artillery; the Russian artillerymen opened fire without bothering to distinguish friend from foe (it was during this cannonade that general d'Hautpoul was mortally wounded). Meanwhile, the remnants of the Russian front line gradually re-formed, firing on the French cavalry.

At this point, the Guard grenadiers arrived, crossing the line in their turn and, carried too far by their momentum, almost got caught. Finally, the chasseurs de la Garde crossed the first two enemy ranks, only to be attacked by Russian cavalry who pushed them back, killed their leader, general Dahlmann, and pursued them to the French lines.

The charge saved the French army by disrupting the Russian center, but the lack of infantry troops prevented Napoleon from making the most of it. The decision would have to be made elsewhere.

The III Corps attack

During the charge, the divisions of the III Corps continued to advance. At around 1 p.m., General Friant, having flushed out Ostermann from the village of Klein-Sausgarten, advanced towards the woods south of Kutschitten [Snamenskoje - Знаменское] and the hamlet of Auklappen , which lay in the Russians' rear.

Morand and Charles Étienne Gudin, who had arrived in the meantime, deployed on his left. The III Corps now formed a south-north line, almost at right angles to the rest of the French army, with the Saint-Hilaire division linking up with it.

With his position in place, Davout resumed the offensive. Friant seized the woods and plateau of Kutschitten , then occupied Lampasch [Nadeschdino - Надеждино] [54.40216, 20.70633]:

Gudin took Auklappen. Bennigsen's reaction, sending in the Ostermann and Kamenski divisions to counter this move, was a failure. By 3 p.m., the French right wing had pushed back the Russian left wing and gained the enemy army's rear.

Now in a bad position, Bennigsen persisted. The imminent arrival of L'Estocq gave him hope. Napoleon, for his part, did not have the troops to deliver the coup. He, too, was awaiting reinforcements from Ney's IV Corps.

The arrivals of L'Estocq and Ney

L'Estocq was ordered to Hussehnen on the evening of February 7, but the state of his troops delayed his departure. Ney was ordered to Landsberg at 2 p.m. on the 8th. Both are on the march, and both are heading for Althof, northwest of the battlefield. Their vanguards collide towards Wackern. Ney tried to cut off his opponent's route to Althof, but the latter thwarted his plans, overtook him and reached the village first, via Graventhien [Awgustowka - Августовка].

By 4 p.m., L'Estocq was in Schmoditten [Rjabinowka - Рябиновка] , from where Bennigsen dispatched him without delay to Kutschitten .

L'Estocq had 7,000 men at his disposal, having left around 2,000 behind: 600 at Althof, the rest to guard the crossing points on the Frisching [Prochladnaja - Прохладная] . His arrival turned the tide of local fighting for a time. He recaptured the woods south of Kutschitten and the village of Auklappen. But Davout was quick to react and stabilize the situation. As night fell, the fighting ceased.

Around 7 or 8pm, Ney arrived in his turn. He immediately attacked the villages of Schmoditten and Schloditten, which he captured and held despite Russian efforts to retake them.

The Russian retreat

Bennigsen realized that the situation no longer gave him much hope of a favorable outcome. His left wing was under pressure from Davout, while his right was beginning to feel Ney's pressure. Short of ammunition and reserves, he decided to withdraw, against the advice of some of his lieutenants and L'Estocq. He nevertheless sang victory to the Tsar.

During the night, the Russian-Prussian army withdrew to Koenigsberg via the Mulhausen road and to Wehlau via the Domnau road .

Napoleon bivouacked that evening on a hill near Ziegelhof, not far from the Landsberg road. The next day, he scoured the battlefield and settled in Preußisch Eylau itself [54.38575, 20.63796], where he remained until February 17, claiming victory all the more firmly as it was less indisputable, even though he had retained control of the terrain.

The aftermath of the battle

Napoleon was well aware that the considerable losses suffered by both sides were more prejudicial to him than to his adversary. As a result, he was particularly cautious in his dispositions, ensuring first and foremost the safety of his army and its communications.

It was only on February 10 that Murat was sent in pursuit of Bennigsen, whom he pushed back beyond the Frisching. But the Emperor was determined not to prolong operations any further and to take up his winter quarters on the Passarge River [Pasłęka]. On the 16th, he gave the order to withdraw.

The fate of the Polish campaign was not yet decided.

A particularly deadly battle (the term "butchery" is used by almost all historians today), the Emperor was deeply affected by his losses, in particular that of seven generals, including his aide-de-camp Claude Corbineau, who was killed by a cannonball.

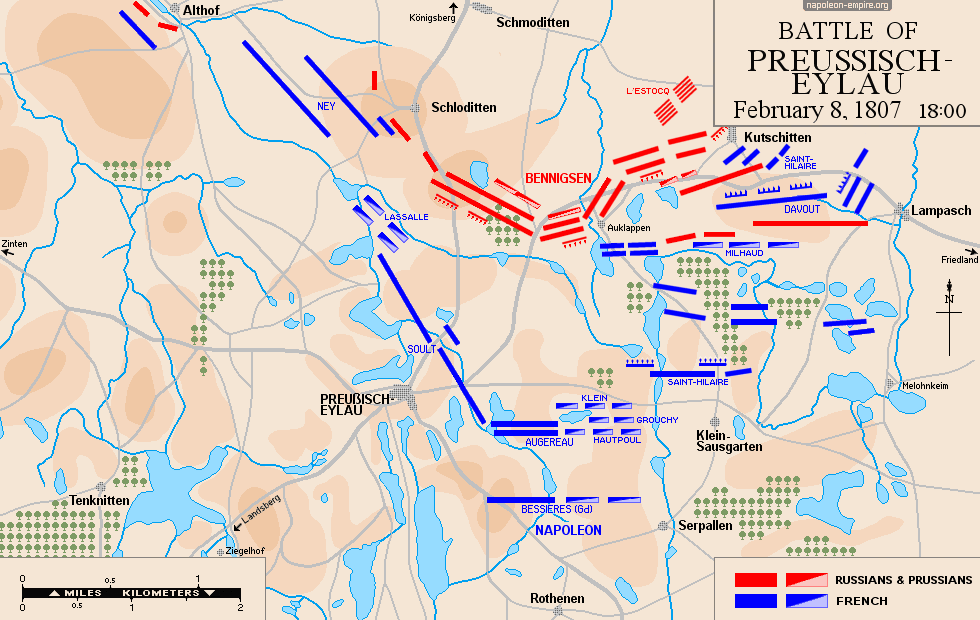

Map of the battle of Eylau

Picture - "Napoleon on the battlefield of Preussisch-Eylau, February 9th, 1807". Painted 1808 by Antoine-Jean Gros.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.