Date and place

- May 21-22, 1809, north of the Lobau, a marshy area on the Danube near Vienna, Austria.

Involved forces

- French army (35,000 men on May 21; 60,000 on May 22) under the command of Emperor Napoleon I.

- Austrian army (around 100,000 men) under Archduke Charles Louis of Austria, Duke of Teschen.

Casualties and losses

- French army: around 6,000 killed, including Marshal Jean Lannes, 20,000 wounded and prisoners.

- Austrian army: more than 24,000 men out of action (dead, wounded, prisoners).

At Essling, Napoleon suffered his first personal setback. Defeat was avoided thanks to Masséna's mastery, but the French had to abandon the field. The losses were enormous. Marshal Lannes, mortally wounded, was the most illustrious victim of the day.

Pre-campaign situation

At the start of the campaign, Napoleon drove back Archduke Charles of Austria to the north bank of the Danube [Die Donau] and quickly captured Vienna [Wien]. But Austria, which still had sufficient forces to continue the struggle, refused to sign the peace treaty.

The French Emperor knew that time was not on his side. His situation would become difficult if the campaign continued. Archduke John of Austria, who had been driven out of Italy by Prince Eugène de Beauharnais and Marshal Étienne Macdonald, could join forces with his brother Charles at any moment, bringing with him a reinforcement of 40,000 to 50,000 men.

To achieve a decisive victory as quickly as possible, Napoleon decided to cross the Danube and attack the Austrian army, positioned five kilometers northeast of the capital, near Bisamberg . Convinced that the Austrian army was about to withdraw, he planned to throw himself on its line of retreat, and did not for a moment consider the possibility of a counter-attack.

The bridges having been destroyed by Archduke Charles, the Emperor, after a first attempt north of Vienna, at Nüssdorf, finally chose to cross not far from Kaiser-Ebersdorf (just east of the capital), relying on the island of Lobau [48.18698, 16.51967]. This island, which divided the Danube into several arms, had the advantage of being both large enough to accommodate the army and wooded enough to conceal it from enemy view.

In addition, the widest branch (seven hundred meters) lay to the south, on the side of the river held by the French, and the two small islands of Schneidergrund and Lobgrund facilitated passage, while the northern branch (one hundred and fifty meters) was situated in such a way that a bridge could be built there under artillery protection.

On May 18, the division of Gabriel Molitor seized the island of Lobau, where it was transported by boat.

The actual building work began on the 19th, under the supervision of Napoleon himself, and all the men, including the officers, took part in the construction. As the main thing was to hurry, to catch the enemy off guard, makeshift solutions were favored, which sometimes proved insufficient.

Everyone was aware, however, that keeping these bridges in good condition was a strategic necessity, and demanded unfailing attention. The alarm raised on May 20, when a ship struck the bridges, causing long delays in the transfer of troops, further underlined the dangers of the situation. Yet Napoleon chose to underestimate the power of the river and the risks it represented. He took a gamble, and lost.

May 21st

During the night of May 19 to 20, 1809, divisions of Marshal André Masséna's IV Corps and Jean Baptiste Bessières' cavalry passed through the island of Lobau, and the following night began to move to the left bank via a bridge built in three hours over the small arm of the river. Damage to the bridges prevented Jean Lannes' IIe Corps and half the Guard cavalry from crossing the same day. Louis-Nicolas Davout's IIIe Corps was one march behind Vienne.

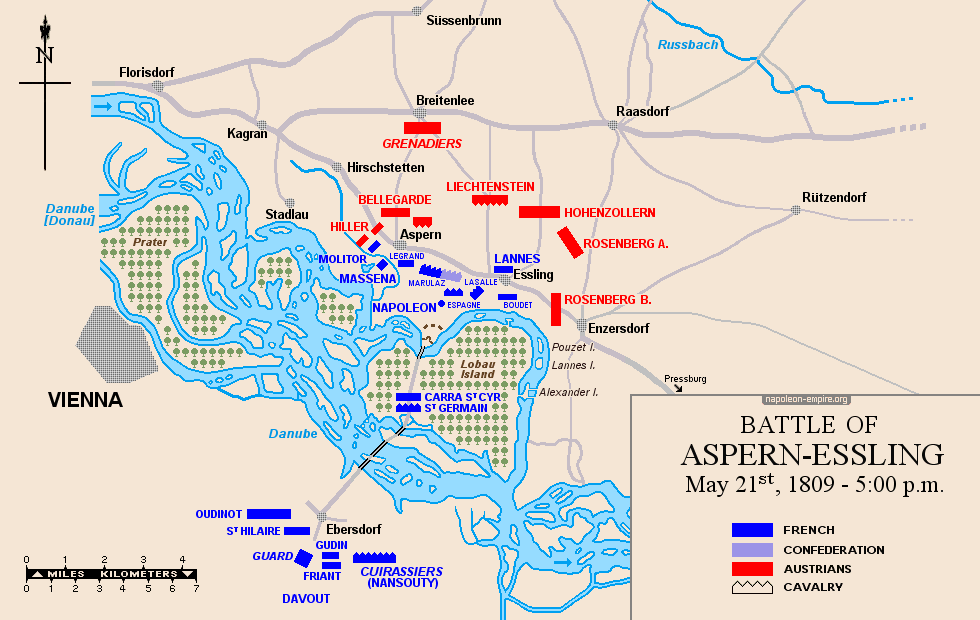

On the morning of the 21st, while the divisions of Claude-Juste-Alexandre Legrand and Claude Carra Saint-Cyr remained in reserve, the Molitor division occupied Aspern (a village of around 100 houses to the west), the Boudet division held Essling (with around 50 houses to the east) and the cavalrymen of Charles Louis de Lasalle and Bessières covered the countryside between the two villages, which formed two bastions.

Tasked with reconnoitring the terrain, but constrained by orders not to come into too much contact with the enemy to avoid an offensive comeback, Lassalle failed to realize the size of the Austrian forces facing the French. Believing they had secured their bridgehead, the French continued their crossing.

Archduke Charles let them. He was waiting for the moment when the French would be numerous enough to merit an attack, but too few to resist.

During the morning and early afternoon, the rest of the IV Corps and the cuirassier division of General Jean Louis Brigitte Espagne successively crossed to the left (north) bank of the Danube. By this time, less than 40,000 French troops had gained a foothold south of the vast Marchfeld plain , stretching from Bisamberg in the west to Pressburg [Bratislava] in the east and the Carpathian Mountains.

The Austrian main army, over 90,000 strong, launched its counter-attack in the middle of the day. From west of Wagram , where it was concentrated, five columns set off simultaneously:

- the first three (under Johann von Hiller , Heinrich von Bellegarde and Friedrich Franz Xaver von Hohenzollern-Hechingen ) were to follow the north bank of the Danube towards Aspern

- the fourth column (under Franz Seraph von Orsini-Rosenberg) headed for Essling

- the fifth (under Ludwig Aloysius von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Bartenstein ) east of Essling, to Gross-Enzersdorf .

These colums were to capture these villages, then converge on the bridge outlets and cut the French off from their base. Isolated and surrounded on the north bank, the French could only succumb under the weight of the immense Austrian numerical superiority.

In accordance with Archduke Charles' plan, the Austrians converged their columns on Aspern and crushed the position with 90 and then 130 cannon fire. By 2.30 p.m., the village was in flames, but two hours later, the Molitor division, led by Masséna, was still holding out. It took the intervention of the Archduke himself for the Austrians to finally take the village.

Faced with the danger posed by this loss, Masséna added the Legrand division to the remnants of the Molitor division, who, expelled at nightfall by forces outnumbering them five to one, immediately reoccupied part of the village, including the cemetery , around which the fighting had been fierce throughout the day.

On the Eßling side, the Boudet division alone, under the command of Marshal Lannes, whose troops had not yet arrived, lost the Enzersdorf outpost at 4 p.m., but managed to hold the rest of its position against considerably more numerous attackers. By evening, the Duke of Montebello was still holding out in a village torched by shells and crushed by bombs.

To relieve the pressure on the infantry in these villages, Napoleon ordered several cavalry charges on the Austrian infantry and artillery during the day. Lassalle and Jacob François Marulaz in the center, Espagne around Essling, led these actions, which proved costly in terms of men, but bought time while new troops crossed the river.

During the fighting, the crossing continued. A steady stream of French soldiers crossed the increasingly precarious bridges now that the river is in flood. The water rose and the current accelerated. The objects thrown into the Danube by the Austrians hit the French structures with redoubled force, causing ruptures that had to be repaired several times, at the cost of colossal efforts.

Night of May 21-22

In control of his bridgehead, Napoleon decided to see Archduke Charles' attack as an opportunity to achieve the all-out battle the Emperor had been hoping for. He therefore took advantage of the night to bring through Marshal Lannes' II Corps, the Guard and the cuirassiers of Raymond Gaspard de Bonardi de Saint-Sulpice and Étienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty, thus reducing his numerical inferiority.

May 22nd

Hostilities began at dawn, around 4am. The mouth of the bridge remained the nerve center of the fighting. To remain in control, the French had to retake Aspern , which they did at seven o'clock when they finally occupied the cemetery, after the village had changed hands four times. To seize it, the Austrians attacked Essling three times and controlled the lower part of the village around the same time, seeking to overrun from the south to reach the bridge. Lasalle and the cuirassiers repelled this threat.

Napoleon, who now had 55-60,000 men at his disposal, resumed the offensive in the center. According to his plan, Lannes' II Corps and the cavalry reserve under Bessières, reinforced during the day by Davout's III Corps and ever-increasing artillery support, were to break through the middle of an enemy position concentrated on its wings, then fall back on them and annihilate them.

At first, the event conformed to the imperial plan. The Austrian center broke between Rosenberg and Hohenzollern; Charles' headquarters at Breitenlee was even threatened. Victory was within reach when the offensive was interrupted by another rupture: the definitive break in the bridges over the first two arms of the Danube. The Austrians had thrown firebombs and other stone-laden boats at them, combined with the lack of protection and the exceptional violence of the current. Davout and his III Corps, the rest of the reserves, ammunition and supplies - everything was blocked on the right bank, for one or two days at least.

The battle could no longer be won; on the contrary, the situation was now desperate. Napoleon gave the order to halt the attack and withdraw in orderly fashion to the bridgehead. The Archduke made the most of the suddenly favorable circumstances. An intensive bombardment preceded a general attack at eleven o'clock.

Charles committed his reserve and personally led the assault, standard in hand. Around midday, the Austrians managed to turn Aspern towards Stadlau, but Masséna, at the head of a Molitor division reduced to the size of a brigade, stopped their movement. As on the previous day, the battle focused on the two villages, which were repeatedly taken and retaken.

Seeing himself unable to break the wings of the French, Charles in turn tried to break through their center. Hohenzollern, reinforced by twelve grenadier battalions and Austrian cavalry, marched on the front held by Lannes. But without success. The Archduke put himself at the head of the attackers, without further success. He then changed his plan again, and moved on Essling, which he took.

Napoleon sent General Mouton and his guard to retake this position, the loss of which could make retreat impossible. Here, as at Aspern, battles broke out in the cemetery and even in the attics . The Austrian grenadiers were finally dislodged.

Unable to advance, the Austrians bombarded the French, who had no choice but to suffer enemy fire. An immediate retreat could quickly turn into a disaster. French army had to wait for nightfall and hold out until then, contenting itself with slowly retreating to the bridge and loosening the grip from time to time with a few cavalry charges.

This decision may well have saved the army, but it cost Marshal Lannes his life when, at around 6 p.m., he was hit by a cannonball that crushed his thigh. He died ten days later as a result of this wound.

At nightfall, under Masséna's leadership, the wounded, equipment and horses were brought back to the island of Lobau . The Marshal was one of the last to cross, at around five in the morning, having the bridge destroyed behind him. The survivors were stranded on the island until the 25th, lacking everything.

After two days of fierce fighting, Archduke Charles was content with this half-success, judging that his army was too exhausted to push on. Pursuing Napoleon to his island, or crossing to the right bank to block him there, seemed too risky an option.

Results

The losses were enormous. On the French side, Marshal Lannes, three generals (Louis Charles Vincent Le Blond de Saint-Hilaire, Jean Louis Brigitte Espagne and Pierre Charles Pouzet) and almost 6,000 men were killed, 20,000 wounded or taken prisoner, representing a total of around 45% of the troops involved.

On the Austrian side, Archduke Charles counted 4,000 dead and 16,000 wounded, probably understating the reality. The intensity of the artillery bombardment and the numerous hand-to-hand street battles that took place in the villages explain this carnage. By the evening of May 21st, the Molitor division had been halved.

The scale of the losses signaled the start of a new, more deadly phase in the Napoleonic wars, in which the growing number of troops involved, the increasingly intensive use of artillery and the reorganization of enemy armies along lines better suited to the new realities made success more difficult and more costly.

Consequences

The consequences were mainly political, as the military situation at the end of the two days was hardly any different from before the battle. But Austrian propaganda, by seizing on what was undoubtedly a failure and presenting it as Napoleon's first defeat, undermined the myth of Napoleonic invincibility. All the Emperor's enemies in Europe were strengthened politically and morally.

On a more strictly tactical level, the Emperor failed to achieve the goal he had set himself, and had to resign himself to prolonging the campaign. What's more, during the course of this battle, he was obliged, contrary to his custom, to leave most of the initiative to the opposing side, regaining it only on the morning of the 22nd, between the resumption of hostilities and the breaking of the bridge. On the other hand, what other army, placed in such a situation, could have avoided a complete disaster?

It would take another month and stronger bridges before a new battle, that of Wagram, would definitively decide the fate of the arms, almost on the same ground.

Map of the battle of Aspern-Essling

Picture - "Napoleon returning to Lobau Island after the Battle of Essling". Painted 1812 by Charles Meynier.

Although some historians consider the battle of Essling-Aspern to be Napoleon I's first defeat and the beginning of the decline of his hitherto invincible army, it is worth noting that it features on the list of victories inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile , and that its name was used to illustrate one of the Empire's most famous marshals, André Masséna.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.