Date and place

- April 22nd, 1809 at Eckmühl [now Eggmühl], fifty kilometers north of Munich, Bavaria and 26 kilometers south-southeast of Regensburg.

Involved forces

- French army of around 35,000 men under Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout, then 100,000 under Emperor Napoleon I.

- Austrian army (80,000 men) under Archduke Charles of Austria, Duke of Teschen.

Casualties and losses

- French army: between 3,500 and 8,000 men dead or wounded, depending on the source.

- Austrian army: 6,000 to 12,000 men out of action, plus 4,000 prisoners.

Aerial panorama of the battlefield of Eckmuehl

The Battle of Eckmühl was the culmination of a series of maneuvers led by Napoleon that resulted in this major victory over Archduke Charles of Austria, who had already been defeated several times in the preceding days in partial engagements. After this new failure, the Austrian commander-in-chief moved to the left bank of the Danube, leaving the road to Vienna open. However, the Austrian army was not destroyed and the Austrian campaign would continue until July.

The general situation

Since Napoleon took command of the campaign on April 18, 1809, the French had racked up successes at Tengen (April 19), Abensberg (April 20) and Landshut (April 21). Nevertheless, the Emperor failed to cut the Austrian army in two, and he had no idea where the bulk of its forces lay. But Archduke Charles' attempt to block the road to Vienna [Wien] by taking Regensburg revealed his position.

From Landshut, Napoleon decided to march north and seek a decisive battle. To prepare for this, Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout was ordered to take the offensive on the 21st, in order to pin the Archduke down in his chosen position.

This move frightened the Austrian commanders, who, fearing that they were already facing Napoleon in person, remained cautiously expectant that day, contrary to their plans. By evening, the Austrians, spurred on by the French, had more or less regained the camp they had left in the morning with offensive intentions.

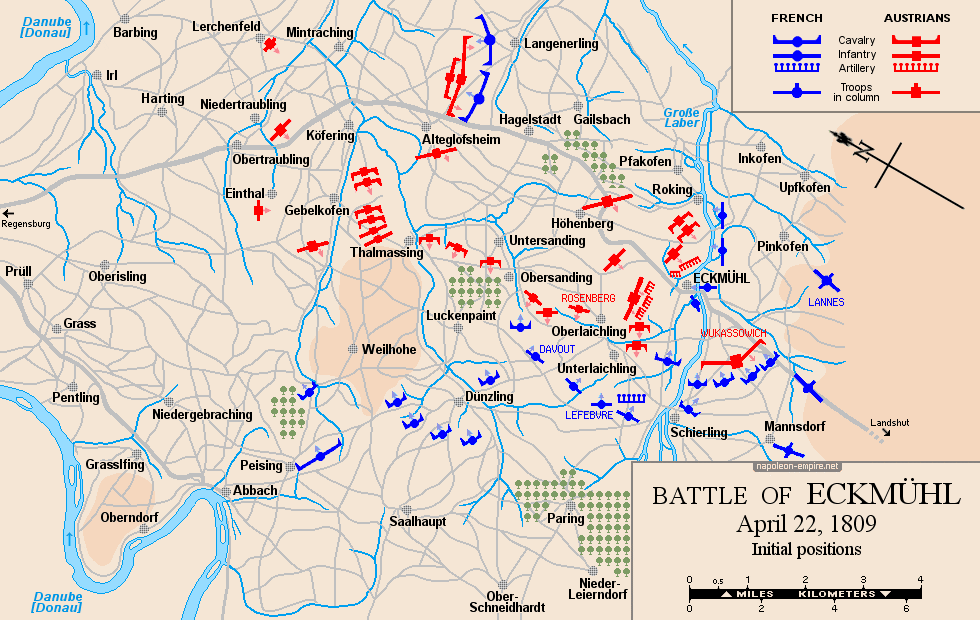

Army positions

The Austrian position was advantageous. Its army, some eighty thousand strong, stretched behind the river Gross Laber , from beyond Eglofsheim [Alteglofsheim] on the right (north) to Leierndorf [Niederleierndorf] on the left (south).

The Austrian line was thus covered by the marshes formed by the river. Various units were also established in villages and on a succession of fairly high hills, densely wooded and difficult to access.

Davout's troops were positioned almost parallel, a little to the west:

- On the left, Louis Friant 's division extended towards Eglofsheim ;

- In the center, Louis Charles Vincent Le Blond de Saint-Hilaire 's division took up positions opposite Unter-Leuchling [Unterlaichling] and Ober-Leuchling [Oberlaichling];

- Marshal François Joseph Lefebvre and his Bavarians, along with the cavalry, were on the right, not far from Schierling .

All in all, the French numbered no more than 30,000 soldiers.

Two sides determined to do battle

Napoleon, like Charles of Austria, took offensive action on April 22.

The Emperor marched on Eckmühl from Landshut, threatening the Austrian left flank. He brought with him the almost complete corps of Jean Lannes and André Masséna, the Württembergers of Dominique-Joseph Vandammme and the cuirassiers of Étienne Marie Antoine Champion de Nansouty . And he sent Marshal Davout the order to attack and break through the enemy center as soon as he saw the divisions of Charles-Étienne Gudin and Charles Antoine Morand approaching, forming the vanguard of the imperial army. In this way, the enemy's left, should it resist, would be enveloped.

For his part, Archduke Charles spent the night of 21st to 22nd preparing an offensive movement. He moved his right wing in front of Regensburg so that his troops formed a line between the Danube and the Große Laber river , stretching from the villages of Abbach [Bad-Abbach] and Peising to Eckmühl . A simple movement of his right wing, falling back on the sparse French troops, could enable him to break through Davout's rear and cut his line of communication.

His planned attack was to be carried out in three columns:

- The first one, of 24,000 men, under the command of Johann Karl von Kollowrat-Krakowsky , would advance from Burg-Weimting towards Abbach.

- The second column, of 12,000 men, commanded by Prince Johann of Liechtenstein , but with the Archduke at its head, was to march on Peising via Weilhohe .

- The third one, comprising the corps of Franz Seraph von Orsini-Rosenberg and Friedrich Franz Xaver von Hohenzollern-Hechingen , reinforced by reserve grenadiers and cuirassiers, was content to defend the road from Landshut to Regensburg.

Its 40,000 men were on the defensive. They were deployed on the slopes of the heights bordering the Große Laber behind the villages of Oberlaichling and Unterlaichling:

The Austrians of this third column thus blocked the Eckmühl causeway, whose castle [48.84401, 12.18357] they occupied, and guarded the entrance to the Regensburg plain towards Egglofsheim. All were ordered to stay put.

At dawn, once the morning fog had cleared, the French observers noticed a great deal of activity in the Austrian camp, foreshadowing an imminent movement. But Charles, aware that his army was the Austrian monarchy's only resource, was reluctant to embark on a venture that might be too bold in the face of an adversary like Napoleon.

Finally, the Archduke decided to wait until the afternoon to attack, to give Kollowrath's corps time to rally at Abbach. He thus let his opportunity slip away. Not a shot was fired before noon.

The fighting

While Charles was dithering, Napoleon advanced. Between noon and one o'clock, his vanguard appeared on the battlefield, arriving from Landshut via Buchhausen . The battle began. The Württembergers, led by Vandamme, seized Lindach [48.82785, 12.16402] and linked up with Lefebvre's Bavarians.

The Gudin and Morand divisions infiltrated between Deckenbach and Zaitzkofen , opposite Eckmühl and Roking [Rogging] .

Davout immediately set about diverting the enemy's attention with a series of false attacks, while the only real one, led by the 10th light infantry regiment, quickly and almost without a blow resulted in the capture of Unter-Leuchling.

The attack on Ober-Leuchling [48.86120, 12.16226] was more deadly, as the attackers were exposed to fire from both the troops occupying the houses and those positioned in the woods above . The village fell, however, and over 1,500 Austrians were taken prisoner. The rest retreated hastily into the surrounding woods .

The French followed them and the battle intensified. The slopes were steep, the paths narrow, and for a while the enemy stubbornly defended themselves. Finally, at the cost of considerable losses, including that of almost all its senior officers, the 10th reached the main road.

But the Austrians had no intention of giving up this strategic point without further effort. They sent a corps of 8,000 men to assault the French. Exhausted and unable to resist such a display of force, the French were relieved to see two regiments of fresh troops arrive and repel the attack.

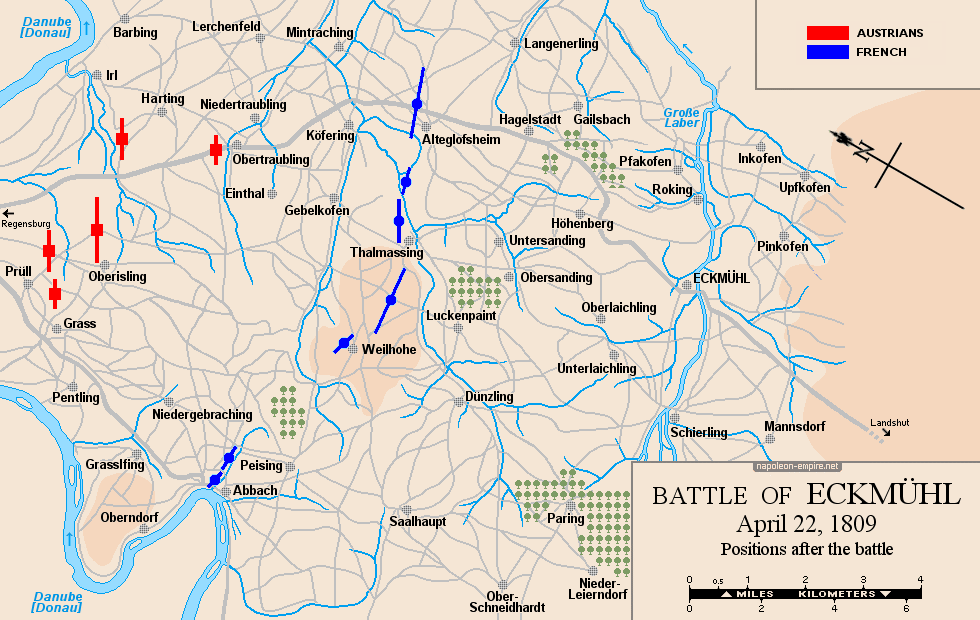

Soon, Rosenberg's entire corps was pushed back towards the Eckmülh causeway.

At the same time, to the south, Lannes, who had crossed the Gross-Laaber at Stanglmühle , above Schierling, flanked the Austrian left wing, which was already under frontal attack from the Württembergers.

The latter advanced along the main road towards Eckmühl, whose castle held out for a while. Although the Austrians tried to rally further back, and their cavalry held off their opponents for a moment until the cuirassiers could intervene, the French advance was so rapid and struck so quickly, its right at Roking , Pfakofen and Gailsbach , its left at Sanding, that it broke all initiative. Overturned in every side, the Austrian left wing was soon in the greatest disarray.

In the north, things were not going so well for Napoleon's soldiers. There, Charles of Austria had attacked the Friant division towards Luckenpoint [Luckenpaint] with such considerably superior forces that he was on the point of overwhelming it, when the setbacks of his left wing forced him to divert his attention and efforts towards it.

The Archduke's efforts will be in vain. Not even his presence could reverse the course of the battle. Soon the Ratisbonne causeway was in French hands. Gudin began to advance across the plain towards Gailsbach. At nine o'clock Charles decided to withdraw.

The bulk of Rosenberg and Hohenzollern's troops retreated to the shelter offered by the mass of Austrian cuirassiers regrouped near Egglofsheim. The French cavalry of Nansouty and Saint-Sulpice, flanked by the Friant and Saint-Hilaire divisions on the left and Gudin on the right, pursued them. The confrontation between the two masses of heavy cavalry, one seeking to cover the retreat of its own, the other one to complete the victory of its camp, turned to the advantage of the French, who forced their opponents to fall back at a gallop from Egglofsheim to Köfering .

However, a new charge by Archduke Charles, who had returned with Johann von Liechtenstein's cavalry reserve to flank the French, combined with the darkness, fatigue and exhaustion of the horses, forced Napoleon to order a halt to the pursuit.

The Austrians retreated as far as the walls of Regensburg. As night fell, Charles had a bridge of boats built across the Danube to enable him to continue his retreat as quickly and discreetly as possible.

Results and aftermath of the battle

Depending on the source, the French army lost between 3,500 and 8,000 men, including the dead and wounded. The Austrians, for their part, left between 6,000 and 12,000 men on the field, plus 4,000 prisoners.

Napoleon, however, had not fully achieved his objective. The Austrians were defeated but not annihilated, and could continue the campaign in Bohemia after crossing the left bank of the Danube.

Map of the battle of Eckmühl - Positions before the battle

Map of the battle of Eckmühl - Positions after the battle

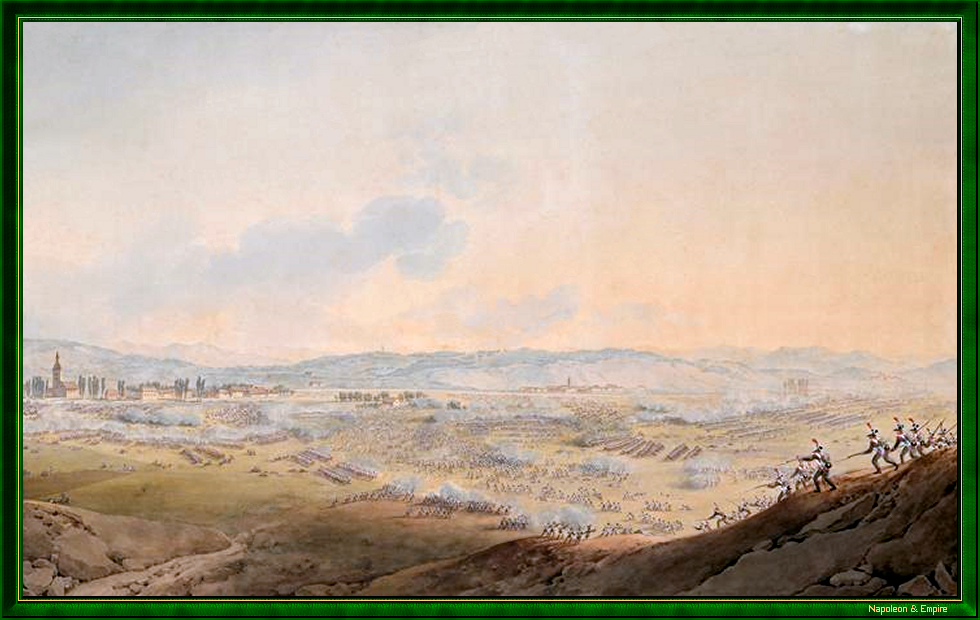

Picture - "Battle of Eckmühl, April 22nd, 1809 at 06:00 PM". Watercolor painting by Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti.

Marshal Davout was made Prince of Eckmühl in recognition of the battle.

General Jean-Baptiste Cervoni , Marshal Lannes' Chief of Staff, was decapitated by a cannonball during the battle, while standing at Napoleon's side. In 1909, a mound was erected on this very spot [48.83774, 12.18351], topped by a monument commemorating the battle.

His grave , meanwhile, is just a few hectometers away [48.83756, 12.18678], in Unterdeggenbach.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.