Date and place

- June 18th, 1815 at Mont-Saint-Jean, south of Waterloo, twenty kilometers from Brussels [Bruxelles], Belgium.

Involved forces

- French army, under Emperor Napoleon the First.

- Prussian-English coalition, with additional troops from Netherlands, Hanover, Nassau and Brunswick, under Field Marshals Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher and Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 24,000 to 26,000 soldiers (killed, injured or prisoners).

- Allied army: 29,500 men killed, injured or prisoners.

Aerial panoramic of the battlefield of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was the final and most decisive battle fought by Napoleon. It ended his epic. The fierce resistance of Wellington, desperately clinging to the ground, the decisive arrival of Blücher's Prussians, overcame the colossal efforts deployed by the French throughout a day that marked the history of the world.

Overview

The Sixth Coalition of 1814 was still gathered in congress in the Ballhausplatz palace in Vienna [Wien] when Napoléon came back to power in Paris on the 20th of March 1815. The coalition straight decided to reject the situation and, without taking into account the pacific intensions of the French Emperor and still considering him as a criminal, immediately began to resume hostility.

It still needed the time, however, to gather its demobilized troups. Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, head of the Prussian troops, and Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, were commanding a coalition of British, Dutch and German troops, were the first ones to reach and gather in Belgium (which was, at that time, part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, created on the 15th of March 1815). Prussians were located in the eastern region, English on the Westside. Russians and Austrians on the other side, only started moving their troops in June.

Napoleon chose to take advantage of this extra time. While he managed to put together an army of 120,000 men, he launched his offensive and crossed the Sambre in Charleroi during the night between the 14th and the 15th of June. This move, being very sudden and unexpected - battle was not expected to start before July - allowed him to slip in between his two opponents. He then intended to successively take care of each of them, his troops being superior in number to those of his opponents.

However, the fights of the next day had a pretty lukewarm outcome for the imperial troops. If Napoleon himself was successful against Bluecher and his Prussian troops in Ligny , 15 kilometers away from Charleroi, his victory wasn’t crucial. His opponents were able to escape.

Furthermore, the same day and despite all its efforts, Marshal Michel Ney could not manage to dislodge Wellington from the crossroads of Quatre Bras , 13 kilometers south of Waterloo. Quatre Bras was a highly central and strategic position at the crossroad of the roads from Brussels to Charleroi and Nivelles to Namur. The conquest of this crossroads could have allowed Ney to reach the back of Blücher’s troops and to destroy them.

However, on the French side, the victory of Ligny got overestimated. When the first reports on the battle were received by the military staff, they were implying that the Prussian army would be heading back towards its operational base in the Meuse. The Emperor then deducted that the main objectives of the start of his campaign (i.e. separating the opponent’s army) were reached.

He could now expect a crucial victory against the English while the new Marshal Emmanuel de Grouchy, at the head of the Cavalry Reserve, III Corps and IV Corps ((Dominique-Joseph-René Vandamme and Étienne Maurice Gérard) would be in charge of preventing the Prussians to come-back to the battle.

However, the Prussian troops were not in such a bad shape. They managed to save most of their artillery, their mood was still bright and Friedrich Wilhelm von Bülow's Corps, who was not in Ligny, was intact. Even better: the outstanding Chief of Staff, General August Neidhardt von Gneisenau, was able to preserve the link with Wellington by organizing the retreat on according to the plan made with his British ally in case of failure.

The next day, on the 17th of June, while Napoleon commanded Grouchy to go after Blücher (even though he would never be able to catch up on his lateness), Wellington, informed of the Prussian defeat, crossed the Dyle and organized his retreat in a safe place south of the Soignes forest and Waterloo, on the plateau of Mont-Saint-Jean, a bit ahead of the village and the farm of the same name [50.68583, 4.40956].

Both allied generals had previously agreed to meet there and Wellington, trusting Blücher to come early with all his army (communications between English and Prussian armies had not been cut), felt ready to accept the idea of a battle happening there.

At first, the French did not notice the move and only noticed it in the afternoon. Napoleon, after reaching Drouet d'Erlon and Ney around the Quatre-Bras, went chasing the Allies. Commanding the vanguard, he chased the British rear-guard and inflicted some casualties.

Then, at around 6 p.m., when arriving around Belle-Alliance [50.66842, 4.41350], and seeing that the allies had taken position, and lacking of sufficient troops to engage the fight, he decided to bivouac the army opposite to the opponents, on a plateau whose centre was in the village of Plancenoit . He himself set up his headquarters at the Caillou Farm [50.64608, 4.42070]. He did not believe, then, in the probability of a battle taking place the next day and he believed until pretty late that Wellington would retreat during the night or at dawn.

Due to this belief, he did not command any systematic recognition of the place. Napoleon was exhausted and did not even react to a note from Grouchy, written in Gembloux, telling him that the Prussians chose to retreat towards Wavre. Such a move was nevertheless a sign of a great threat coming from the two enemy armies. But the Emperor did not believe in the reality of this threat, not that early after the battle like the Ligny one.

The night passed and happened to be awful for soldiers on both sides. The rain kept pouring and a frozen wind kept blowing from the East. The British and Dutch only had makeshift shelters and limited supplies. It was even worse on the French side as they arrived too late in the night to be able to light a fire or build a shelter. They had to sleep on the muddy floor, among wet wheat ears.

Prelude

Wellington’s strategy

The Duke's strategy was pretty simple: hold everything together and wait for Blücher’s arrival. He had no other choice as his retreat line was not guaranteed. Behind him, he only had a procession that would turn any retreat into a disaster.

Blücher, on his side, tried to keep up with his commitment:

- Early in the morning he sent his IV corps, of Friedrich Wilhelm Bülow von Dennewitz , towards Chapelle Saint-Lambert, through Wavre , in order to attack the French army from the side if the battle had already started when he was going to arrive.

- The II Corps, of Georg Dubislav Ludwig von Pirch , was closely following it.

- The I Corps, of Hans Ernst Karl von Zieten , received command to march a bit more North in order to reach the left side of Wellington’s army.

- The III Corps, of Johann von Thielmann , had to keep Grouchy at bay in order to give the three other corps the freedom they needed to take action.

Napoleon’s strategy

On the morning of the 18th of June, it became obvious that Wellington had not started to retreat during the night. This information had been confirmed by the Belgium deserters. Napoleon was happy about it. He was even fearing that the bad weather would prevent him from benefiting from the belligerent apparatus of its enemy.

He was willing to attack as early as possible, around 9 a.m., but the weather conditions were too bad, the soil was so wet, that he had to wait. After the artillerymen confirmed that the soil was dry enough for them to be able to manoeuver properly, Napoleon climbed the Rossomme knoll in order to observe the place. From this point, he could see the Hougoumont Forest and the Haie-Sainte, but not the position taken by the Allies for their defense. Furthermore, he received General François Nicolas Benoît Haxo’s report, who was just coming back from a reconnaissance, and that did not mention (wrongly) any fortifications.

Finally answering to Grouchy’s letter that he had received during the night, he commanded him to move towards Wavre in order to « link communications ». Then, around 11 a.m., he dictated his order of battle.

Once the army will be ready for the battle, at around 1 p.m., and when the Emperor will command Marshall Levy, the battle will start in order to seize the village of Mont-Saint-Jean where there is the crossroads. In this regard, the battery 12 from the II and the VI Corps will come together with the I Corps. These 24 pieces of artillery will fire the Mont-Saint-Jean troops and D’Erlon will start attacking by putting forward his left division which will be supported, if needed, by the divisions of the I Corps.

The II Corps will step forward in order to keep d’Erlon’s height. The companies of sappers from the I Corps will be ready to shield itself at Mont-Saint-Jean.

Napoleon’s strategy was to attack the weakest point of the enemy: its left side. Therefore, the effort had to be concentrated on the East side and the centre (Haye Sainte farm ) to try taking the Brussels road which was the only line of retreat for the Allies.

A large artillery support was planned and deployed in front of the I corps. It would include not 24 but 80 cannons. This would be known as the "Grand Battery".

Finally, in order to force Wellington to strengthen his right side at the expense of its left side, the division of Jerome Bonaparte, II Corps (commanded by General Honoré Charles Reille ), would conduct a fake attack on the Hougoumont Farm.

The Allied troops layout

Wellington had a multinational army with around 68 to 71,000 men: 25,000 British, 17,000 Dutch (including Belgium, who were at that time subject of the Dutch Kingdom), 10,000 from Hanover, 7,000 from Brunswick, 6,000 men from the King's German Legion, 3,000 from Nassau, and a few French royalists. His artillery counted 184 guns.

Troops were ready to fight on the Plateau Mont-Saint-Jean, south of the village of the same name, astride the road from Charleroi to Brussels.

As they were deployed most of the time against the slope, to better protect them and hide their movements, they were facing south and had three points of support ahead of their front that they had fortified and well provided with defenders. These are, from east to west:

- the Papelotte Farm [50.68010, 4.43363] (near the hamlet of La Haie);

- the Haye-Sainte Farm [50.67801, 4.41228];

- the castle-farm of Hougoumont [50.67060, 4.39465].

The left side (east side) was protected by a steep gully heading towards the village of Ohain. The reserve was in Mont-Saint-Jean and even the cavalry, organized on three lines, was staying backward the army.

The front was about 4,000 meters long. Two detachments, the first one in Tubise, the second in Clabbeck and Braîne-le-Château were watching over the road to Mons.

The position of French troops

Napoleon had about 73,000 men, that number gave him a very slight numerical superiority over Wellington. As far as the artillery was concerned, his advantage was much greater since he had 266 cannons, that is to say 82 more than his opponent.

The army got ready for the battle about 1 kilometer away from the Plateau.

The right side (east) was formed of the I Corps commanded by Drouet d'Erlon (composed of 20,000 men), the 2,700 cavalrymen from the cavalry corps commanded by Jean-Baptiste Milhaud and the division of cavalry of the Garde commanded by Charles Lefèbvre-Desnouettes (2,000 cavalrymen). It was going from the road to Brussels until right in front of the Papelotte farm.

The left side (west) was formed of II Corps commanded by Reille with 20,000 men as well, followed by 3,400 cavalrymen from the cavalry corps commanded by François-Etienne Kellermann and the division of cavalry of the Guard commanded by Claude Étienne Guyot (2,100 cavalrymen). It was going from the left side of the road to Brussels until the Hougoumont forest which was also covered by Jerome on the extreme left side of the apparatus.

The two sides were on the front. Further backwards, there was the VI Corps commanded by Georges Mouton, Count of Lobau, with 10,000 men only, the division of cavalry commanded by Jean-Siméon Domon and Jacques-Gervais Subervie (more than 1,200 cavalrymen each) and three infantry divisions of the Guard (9,000 men in total). Its exact position varies according to the different Napoleonic reporting (bulletin, dictation of 1818, dictation of 1820) but which seems to have been placed, in fact, according to most witnesses and as reported by the bulletin published immediately after the facts, behind the right side of the I Corps.

Finally, many guns were concentrated to the right side of the road, on a ridge, in front of the Belle-Alliance:

The battle

The diversionary attack on Hougoumont

Around 11 or 11:30 a.m., the attack on Hougoumont hit the three shots of the battle. But Napoleon's orders were misinterpreted. While he had ordered a simple demonstration on the hamlet and its surroundings, in order to keep the enemy there, his brother Jerome persisted during the whole day to try to seize the farm and the castle, whose buildings, fortified, were held by several companies of English Guards and troops just like the surrounding wood.

The first assault was launched thirty steps away from the farmhouse by a heavy gunshots coming from the wall. At noon, despite the advice of his chief of military the General Armand Charles Guilleminot , who just wanted to settle for the woods, Jerome triggered a new attack. This time he had artillery support and their joint effort helped pushing the English soldiers towards the buildings. The south gate stopped them, not the north which got open with axes. The French infantry penetrated for a moment in the gardens. After very heavy fighting and heavy losses (only a young drum will survive from the attack), the army could not keep up.

From 2 p.m., the French howitzers came into action and pounded the farm. Several hundred defenders died in the fire caused by the bombing. However, what remained of troops outside was holding on and kept control of the place.

Then, the Maximilien Sébastien Foy 's division got involved. Finally, three entire divisions were going to be wasted in this useless fight. 8,000 men got mobilized to face 2,000, against the intentions of Napoleon. The whole, at the cost of considerable losses, that ended up obtaining no appreciable result.

Prussians’ first appearance

While the I Corps main attack was being planned, and while the big battery was about to take action, at around 1 p.m., a movement of troops was spotted just out of the Chapelle-Saint-Lambert woods, about 8 kilometers east of the battlefield.

Pretty soon, French scouts said it was Prussians. An intercepted letter on a Prussian hussar NCO soon confirmed that it was the vanguard of the Bülow’s IV Corps with 30,000 men arriving through Lasne and the wood of Paris where there was no French detachment to stop him.

The French army was running the risk to see the Prussians troops appearing on its right side, or even worse, from behind.

Napoleon ordered the writing of a letter to Grouchy asking him to hurry up to join the battlefield and to stop getting distracted by the Prussians’ strategy. It seemed that this command, given by Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult to a single messenger – Sir, Berthier would have sent a hundred

would later tell him the Emperor when learning it – got lost or arrived way too late. Grouchy, without this letter and despite the objurgating of his subordinate to go join, would never make it.

Being forced to protect his right side and his rear, Napoleon sent two divisions of light cavalry (division Domon and division Subervie), beyond Plancenoit. Their mission was to observe the enemy, to contain him and to join Grouchy’s columns as soon as they would appear. Finally, the VI Corps command made it possible to stop 30,000 men with only 10,000.

This strategy involved nearly 13,000 that would, thus, not be able to take part into the offensive on Mont-Saint-Jean.

I Corps attack

It started around 12:30 or 1 p.m. with half an hour of very intense artillery preparation, led by the great battery of 80 guns which was long enough to cover 1,400 meters facing the Anglo-Dutch center. But this cannonade did not end up having the expected result. The enemy was hidden behind the ridge of the plateau and the shooting could be nothing but approximate.

Moreover, the balls were not ricocheting on the muddy ground, the shells were only exploding and projecting harmless cataracts of muddy soil.

Around 1.30 p.m., 17,000 infantrymen from the I Corps commanded by Drouet d’Erlon attacked on a line that went from the Haie-Sainte farm to the Papelotte one. They were arranged according to an unusual set up, which was going to be catastrophic. The battalions were lined up one behind another in compact masses, 180 men wide by 24. They were both extremely vulnerable to enemy cannons and difficult to manoeuvre, especially in the event of a cavalry attack.

Without having to seize both the farms, the French infantry still managed to take the plateau when Wellington launched a counter attack. The unfortunate disposition of the troops then revealed its harmfulness. After having already multiplied the losses during the assault, the disposition then paralyzed the movements of the troops when they had to deploy. The compact mass of French soldiers stomped, unable to manoeuvre.

The enemy took advantage of the situation. While the enemy troops had undergone the cannonade lying in the rye, they lead a bayonet charge on the sides of the French column. The Scottish infantry of General Sir Thomas Picton (who got killed in the action) rushed on the opponent who was completely confused. Upon Wellington’s command, Lord Uxbridge (Henry William Paget, 2nd Earl of Uxbridge) had Lord Robert Somerset ’s heavy cavalry regiments and Sir William Ponsomby 's Union Brigade sent.

The French flew back, completely confused, among English cavalrymen. The reflux movement carried off all the assailants of Haye-Sainte. Those of Papelotte found themselves unprotected and loaded by the English dragons but nevertheless managed to maintain order in their retreat.

Carried away by their success, the two brigades of British cavalrymen continued to charge until the big battery. But there, disorganised, stunted by their tired horses, they underwent the simultaneous counter-attack of two brigades of cuirassiers commanded by General Milhaud and the 4th regiment of imperial lancers who both annihilated them. Wellington had no more cavalry.

The I Corps attack was, nonetheless, a complete failure. Its 2nd and 3rd divisions were totally disorganized. The 1st and the 4th one would only intervene in skirmishes against the English line, on Haye-Sainte or on the hamlet of Smohain. The English centre was still holding on.

Marshal Ney's charges

Napoleon had no other choice than leading a second attack. In-between 3 and 4 p.m., while the I Corps reorganized, the big battery made a new preparation shot. The attack on Haye-Sainte failed again, however, Wellington had made his centre troops move slightly in order to re-align them and put them in a safer place, away from the cannonade. Ney saw in this movement the sign of a retreat and decided to take advantage of it. It was about 4 p.m.

Taking this decision by himself, Napoleon, sick and having temporarily left the battlefield, Ney sent the cuirassiers of Jean-Baptiste Milhaud and Jacques-Antoine-Adrien Delort as well as the hunters and lancers of Lefebvre-Desnouettes on the centre-right of the enemy line, which was still intact, between Haye-Sainte and Hougoumont. The Emperor, who was then at the Decoster house [50.66410, 4.41377], must have seen the movement. He did not intervene.

When Napoleon returned to the battlefield, the two first loads had already failed. The Emperor was disapproving of Ney’s initiative but, reluctantly and pushed by his staff, still decided to support it. At 5pm, the carabineer and cuirassiers of Kellermann’s corps, as well as the mounted grenadiers and the dragoons of the guards from the Guyot’s division were sent to reinforce Ney, gathering under his command 10,000 horses. All the French cavalry was engaged, but they neglected to have it backed up by the artillery!

French cavalry collided with the British infantry that was formed into a square shape, the best shape to resist them. They were not going to succeed to push into them. Loads were lacking power and energy on the heavy and steep ground. In addition, the enemy artillery took a heavy toll on the attackers. However, they were going to neglect to put in or take away the enemy cannons that their crews, after striking the assailants, abandoned to be able to seek shelter in the squares. After that, they would return to their intact pieces when the French would pull out and then replay the same strategy on the next attempt.

Ney persisted into this suicidal back and forth for two hours. The British troops, despite their heavy losses, remained stoic and disciplined in front of the attacks. The Marshal attacked again and again twelve times. Three of the horses he was riding got killed but nothing would stop him. At around 5.30 p.m., the French cavalry was almost destroyed. Napoleon had 800 carabineers remaining. After making the mistake of launching the attacks without the support of infantry, Ney ended up asking Napoleon for it. But the Emperor had no more infantry supply. The intervention of the Prussians had already ended them.

Prussians’ intervention

Around 5 p.m., the Prussian IV Corps commanded by Bülow attacked Plancenoit, from where he would threaten the right side of the French troops and even cut their line of retreat. Indeed, the French VI Corps which was facing them was outnumbered (1 man against 3) and started pulling out to the point that the bullets and the Prussian fire guns began to fire the Belle-Alliance and the roadway, where the Guard was standing.

Napoleon had no other choice but to send to Lobau two divisions from the Young Guard under the command of Guillaume Philibert Duhesme , then two regiments of grenadiers and foot-hunters from the old guard under the command of Charles Antoine Louis Alexis Morand and Jean-Jacques Germain Pelet-Clozeau so that their joint efforts would make it possible to take over the village and contain Bülow. The extremely violent fights continued until 8 p.m.

At the same time, on the extreme right of the French apparatus, General Pierre François Joseph Durutte and his division were trying to prevent any connection between the Prussians and the left side of Wellington’s troops. At this end, they seized the hamlet of Smohain.

All these forces that were consumed against the Prussians helped stabilizing the right side of the imperial army but also relieved the pressure against Wellington’s troops.

The last attack of the Imperial Guard

And that was exactly what the Duke of Wellington needed. At that point, he was going through the most critical time of the fight.

Around 6 p.m., the French finally seized Haye-Sainte. The leader of its defenders, Major Konrad Ludwig Georg Baring of the King's German Legion, had only 42 with him when he decided to abandon the farm. These 42 men were the only survivors of the nine forces!

Ney had a few cannons put into the battery, the fire of which destroyed the allied line. An infantry back up would had make it possible to exploit this success and perhaps to finally make it through the line.

But Napoleon only had a few battalions of the Guard and he was hesitating to engage them while the Prussians were still threatening his back to Plancenoit. Around 7:30 p.m., however, once the situation was restored on this point, he took the decision to launch one last attack gathering all the men that were still valid and with which the Guard would be the spearhead, under the command of Marshal Ney. It was necessary to pierce the lines before the arrival of the main Prussians troops, arrival that was becoming more and more imminent.

Indeed, the vanguard of the Prussian I Corps of Ziethen had been reported to be heading in the direction of Ohain at around 7 p.m.

Napoleon, to avoid the mood of his troops to go down, spread the rumour that it was in fact Grouchy even though he knew that it was not. He also knew that he had to take a decision while it was still time. At 7:30 p.m., Ziethen, despite some hesitation, had already reached Smohain and Papelotte, allowing Wellington to tighten the ranks of his centre by weakening his left, where the Prussians would compensate for it.

So that when the Imperial Guard climbed the foothills of the plateau, at a place that was not well chosen because it was not the weakest of the enemy apparatus, it had been greeted by the most terrible fire of artillery and musketry. The riflemen of General Peregrine Maitland , lying in the wheat, waited until the Guard was only a few steps away to suddenly rise before it and hit it, like red devils. At the same time, the Dutch of General David Hendrik Chassé , attacked its flanks with canisters.

Completely outnumbered (nine battalions, not more than 6,000 men in all) and without the support of neither the cavalry nor the artillery, the Grognards had no alternative but to retreat for the first time in their history.

The French meltdown

Witnessing this and noting that Blücher (and not Grouchy as promised to them) whose troops had pierced near the hamlet of La Haie, flooding the battlefield with their cavalry, was arriving, the French unites started to disband. At Plancenoit, von Bülow received back up from the II Prussian Corps and started increasing his pressure and directly threatening the rear of the French troops.

Wellington then moved his army down the plateau, taking the French between him and the Prussians. The Allies separated the I Corps of D'Erlon from the battalions of the Guard who were retreating towards the Belle-Alliance. All organized resistance ceased. The I Corps disintegrated, soon followed by the II, the VI and the cavalry.

Only the two battalions of the 1st regiment of Grenadiers, formed in squares, managed to contain the enemy for a short while. However, overwhelmed on all sides, their position soon became untenable and Napoleon himself commanded their withdrawal. They conducted it in good order, collecting on their ways whatever was left from the troops.

The Emperor himself, Marshals Soult and Ney, Generals Henri-Gatien Bertrand , Antoine Drouot and Charles de La Bédoyère seeked shelter among them.

It was during these pathetic moments that French General Pierre Cambronne, from the middle of the square of hunters of the Old Guard that he commanded, would have responded to the surrender offers of English general Charles Colville with this famous phrase: La Garde meurt mais ne se rend pas

("The Guard dies but does not surrender"). The British's insistence then led him to condense his response. His resounding Merde!

("Shit!"), which he would always deny having uttered, has since become the Cambronne word

.

At 9 p.m., the battle was over.

A little later, the two winners met at Belle-Alliance and agreed to let the Prussians in charge of the pursuit.

The energy Blücher was going to put into this pursuit, as usual, would be turning defeat into an irreparable disaster.

The remains of the French army had reached Genappe by the road to Charleroi . This is where the defeat turned into a rout. Crossing the bridge over the Dyle caused new disorders. The fugitives fought against each other to flee more quickly, and the French, who thought they would spend the night there, were driven out by the Prussians who arrived there at eleven o'clock at night.

Napoleon himself, who was attempting to rally a rear-guard corps, almost gor caught there and had to abandon his sedan, with everything in it, to the hands of the enemy. Around 1 a.m., he reached Quatre Bras.

The fugitives from the I and II Corps, passed the Sambre River in Marchiennes but crossed Quatre-Bras and Gosselies without anyone stopping them to reorganize them. The Guard, the remains of the VI Corps and the cavalry retreated to Charleroi, just like the Emperor.

Meanwhile, Wellington went back to his headquarter , wrote his report and named the battle after the name of the village he was at: Waterloo.

Outcome of the battle and consequences

Although considered as the winners, the Allies suffered in Waterloo losses equivalent to those of the French. On 18 June they deplored the loss of 29,500 men, including 8,300 Britons, 9,500 Dutch, Belgians and Hanoverians and 8,300 Prussians. But, without even counting Russians and Austrians, who were marching towards the French border, they had back-ups which Napoleon did not have.

The Emperor had in fact lost most of his maneuvering mass. Only the Corps of Grouchy and the garrisons of the strongholds were left to fight. The great victory that would be able to bring the Allies to the negotiating table would never be his.

As the political situation in Paris would soon get out of his hands, he headed to Paris even though he was not willing to but pushed by his generals (that is what has been reported by french captain and memorialist Jean-Roch Coignet). Four days later, despite the crowd gathered in front of the Elysee Palace to shout: Long live the Emperor

, he abdicated. The 1st Empire was finally over. The legend was about to start.

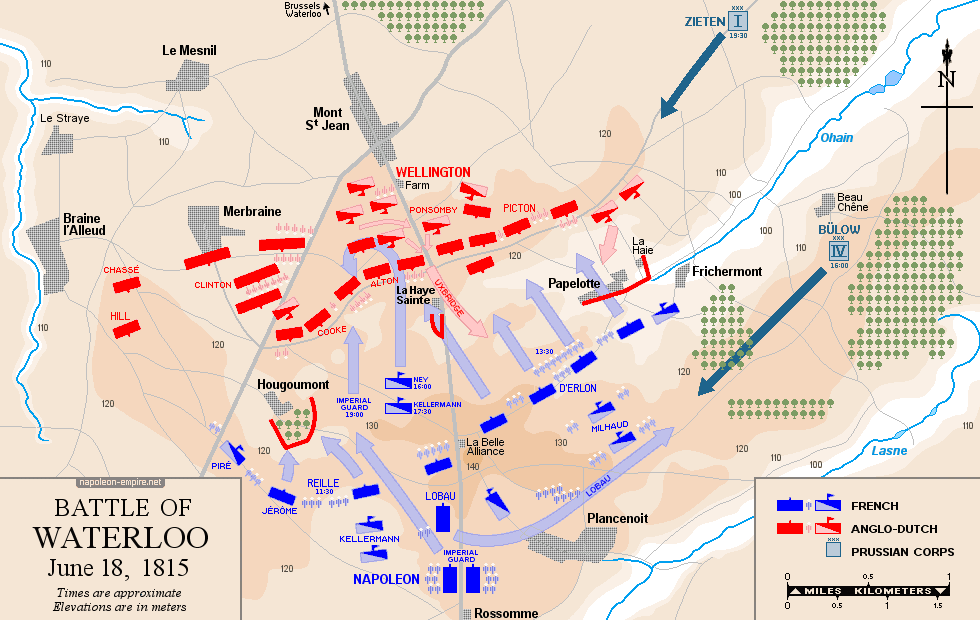

Map of the battle of Waterloo

Picture - "The Battle of Waterloo". Painted 1874 by Henri-Felix-Emmanuel Philippoteaux.

According to some military theorists, the Battle of Waterloo opened a new area in military tactics, linked to the power increase of the artillery, during which the defence will take precedence over the attack. The situation would change again only with the Second World War.

A bronze statue of the Emperor , the work of the sculptor Luigi di Quintana Bellini Trinchi, was erected in 2002 near the Caillou farm (nowadays a Napoleonic museum).

A 43-meter-high mound , surmounted by a cast-iron lion looking towards France, was erected by the Netherlands ten years after the battle, at the place where the Prince of Orange got wounded during the battle.

The legend has it that Marshal Grouchy, marching on Wavre according to the orders of the Emperor, took the time to lunch succulent strawberries at the Marette farm in Walhain, while his deputy General Maurice Etienne Gérard urged to walk "to the sound of the cannon" towards Mont-Saint-Jean, which he did not do.

Testimony

To Earl Bathurst.

Waterloo, 19th June' 1815.

MY LORD,

Buonaparte, having collected the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 6th corps of the French army, and the Imperial Guards, and nearly all the cavalry, on the Sambre, and between that river and the Meuse, between the 10th and 14th of the month, advanced on the 15th and attacked the Prussian posts at Thuin and Lobbes, on the Sambre, at day-light in the morning.

I did not hear of these events till in the evening of the 15th; and I immediately ordered the troops to prepare to march, and, afterwards to march to their left, as soon as I had intelligence from other quarters to prove that the enemy's movement upon Charleroi was the real attack.

The enemy drove the Prussian posts from the Sambre on that day; and General Ziethen, who commanded the corps which had been at Charleroi, retired upon Fleurus; and Marshal Prince Blücher concentrated the Prussian army upon Sombref, holding the villages in front of his position of St. Amand and Ligny.

The enemy continued his march along the road from Charleroi towards Bruxelles; and, on the same evening, the 15th, attacked a brigade of the army of the Netherlands, under the Prince de Weimar, posted at Frasne, and forced it back to the farm house, on the same road, called Les Quatre Bras.

The Prince of Orange immediately reinforced this brigade with another of the same division, under General Perponcher, and, in the morning early, regained part of the ground which had been lost, so as to have the command of the commumication leading from Nivelles and Bruxelles with Marshal Blücher's position.

In the mean time, I had directed the whole army to march upon Les Quatre Bras; and the 5th division, under Lieut. General Sir Thomas Picton, arrived at about half past two in the day, followed by the corps of troops under the Duke of Brunswick, and afterwards by the contingent of Nassau.

At this time the enemy commenced an attack upon Prince Blücher with his whole force, excepting the 1st and 2nd corps, and a corps of cavalry under General Kellermann, with which he attacked our post at Les Quatre Bras.

The Prussian army maintained their position with their usual gallantry and perseverance against a great disparity of numbers, as the 4th corps of their army, under General Bülow, had not joined; and I was not able to assist them as I wished, as I was attacked myself, and the troops, the cavalry in particular, which had a long distance to march, had not arrived.

We maintained our position also, and completely defeated and repulsed all the enemy's attempts to get possession of it. The enemy repeatedly attacked us with a large body of infantry and cavalry, supported by a numerous and powerful artillery. He made several charges with the cavalry upon our infantry, but all were repulsed in the steadiest manner.

In this affair, His Royal Highness the Prince of Orange, the Duke of Brunswick, and Lieut. General Sir Thomas Picton, and Major Generals Sir James Kempt and Sir Denis Pack, who were engaged from the commencement of the enemy's attack, highly distinguished themselves, as well as Lieut. General Charles Baron Alten, Major General Sir C. Halkett, Lieut. General Cooke, and Major Generals Maitland and Byng, as they successively arrived. The troops of the 5th division, and those of the Brunswick corps, were long and severely engaged, and conducted themselves with the utmost gallantry. I must particularly mention the 28th, 42nd, 79th, and 92nd regiments, and the battalion of Hanoverians.

Our loss was great, as your Lordship will perceive by the enclosed return; and I have particularly to regret His Serene Highness the Duke of Brunswick, who fell fighting gallantly at the head of his troops.

Although Marshal Blücher had maintained his position at Sombref, he still found himself much weakened by the severity of the contest in which he had been engaged, and, as the 4th corps had not arrived, he determined to fall back and to concentrate his army upon Wavre; and he marched till the night, after the action was over.

This movement of the Marshal rendered necessary a corresponding one upon my part; and I retired from the farm of Quatre Bras upon Genappe, and thence upon Waterloo, the next morning, the 17th, at ten o'clock.

The enemy made no effort to pursue Marshal Blücher. On the contrary, a patrole which I sent to Sombref in the morning found all quiet; and the enemy's vedettes fell back as the patrole advanced. Neither did he attempt to molest our march to the rear, although made in the middle of the day, excepting by following, with a large body of cavalry brought from his right, the cavalry under the Earl of Uxbridge.

This gave Lord Uxbridge an opportunity of charging - them with the 1st Life Guards, upon their débouché from the village of Genappe, upon which occasion his Lordship has declared himself to be well satisfied with that regiment.

The position which I took up in front of Waterloo crossed the high roads from Charleroi and Nivelles, and had its right thrown back to a ravine near Merke Braine, which was occupied, and its left extended to a height above the hamlet Ter la Haye, which was likewise occupied. In front of the right centre, and near the Nivelles road, we occupied the house and gardens of Hougoumont, which covered the return of that flank; and in front of the left centre we occupied the farm of La Haye Sainte. By our left we communicated with Marshal Prince Blücher at Wavre, through Ohain; and the Marshal had promised me that, in case we should be attacked, he would support me with one or more corps, as might be necessary.

The enemy collected his army, with the exception of the 3rd corps, which had been sent to observe Marshal Blücher, on a range of heights in our front, in the course of the night of the 17th and yesterday morning, and at about ten o'clock he commenced a furious attack upon our post at Hougoumont. I had occupied that post with a detachment from General Byng's brigade of Guards, which was in position in its rear; and it was for some time under the command of Lieut. Colonel Macdonell, and afterwards of Colonel Home; and I am happy to add that it was maintained throughout the day with the utmost gallantry by these brave troops, notwithstanding the repeated efforts of large bodies of the enemy to obtain possession of it.

This attack upon the right of our centre was accompanied by a very heavy cannonade upon our whole line, which was destined to support the repeated attacks of cavalry and infantry, occasionally mixed, but sometimes separate, which were made upon it. In one of these the enemy carried the farm house of La Haye Sainte, as the detachment of the light battalion of the German Legion, which occupied it, had expended all its ammunition; and the enemy occupied the only communication there was with them.

The enemy repeatedly charged our infantry with his cavalry, but these attacks were uniformly unsuccessful; and they afforded opportunities to our cavalry to charge, in one of which Lord E. Somerset's brigade, consisting of the Life Guards, the Royal Horse Guards, and 1st dragoon guards, highly distinguished themselves, as did that of Major General Sir William Ponsonby, having taken many prisoners and an eagle.

These attacks were repeated till about seven in the evening, when the enemy made a desperate effort with cavalry and infantry, supported by the fire of artillery, to force our left centre, near the farm of La Haye Sainte, which, after a severe contest, was defeated; and, having observed that the troops retired from this attack in great confusion, and that the march of General Bülow's corps, by Frischermont, upon Planchenois and La Belle Alliance, had begun to take effect, and as I could perceive the fire of his cannon, and as Marshal Prince Blücher had joined in person with a corps of his army to the left of our line by Ohain, I determined to attack the enemy, and immediately advanced the whole line of infantry, supported by the cavalry and artillery. The attack succeeded in every point: the enemy was forced from his positions on the heights, and fled in the utmost confusion, leaving behind him, as far as I could judge, 150 pieces of cannon, with their ammunition, which fell into our hands.

I continued the pursuit till long after dark, and then discontinued it only on account of the fatigue of our troops, who had been engaged during twelve hours, and because I found myself on the same road with Marshal Blücher, who assured me of his intention to follow the enemy throughout the night. He has sent me word this morning that he had taken 60 pieces of cannon belonging to the Imperial Guard, and several carriages, baggage, &c., belonging to Buonaparte, in Genappe.

I propose to move this morning upon Nivelles, and not to discontinue my operations.

Your Lordship will observe that such a desperate action could not be fought, and such advantages could not be gained, without great loss; and I am sorry to add that ours has been immense. In Lieut. General Sir Thomas Picton His Majesty has sustained the loss of an officer who has frequently distinguished himself in his service, and he fell gloriously leading his division to a charge with bayonets, by which one of the most serious attacks made by the enemy on our position was repulsed, The Earl of Uxbridge, after having successfully got through this arduous day, received a wound by almost the last shot fired, which will, I am afraid, deprive His Majesty for some time of his services.

His Royal Highness the Prince of Orange distinguished himself by his gallantry and conduct, till he received a wound from a musket ball through the shoulder, which obliged him to quit the field.

It gives me the greatest satisfaction to assure your Lordship that the army never, upon any occasion, conducted itself better. The division of Guards, under Lieut. General Cooke, who is severely wounded, Major General Maitland, and Major General Byng, set an example which was followed by all; and there is no officer nor description of troops that did not behave well.

I must, however, particularly mention, for His Royal Highness's approbation, Lieut. General Sir H. Clinton, Major General Adam, Lieut. General Charles Baron Alten (severely wounded), Major General Sir Colin Halkett (severely wounded), Colonel Ompteda, Colonel Mitchell (commanding a brigade of the 4th division), Major Generals Sir James Kempt and Sir D. Pack, Major General Lambert, Major General Lord E. Somerset, Major General Sir W. Ponsonby, Major General Sir C. Grant, and Major General Sir H. Vivian, Major General Sir O. Vandeleur, and Major General Count Dornberg.

I am also particularly indebted to General Lord Hill for his assistance and conduct upon this, as upon all former occasions.

The artillery and engineer departments were conducted much to my satisfaction by Colonel Sir George Wood and Colonel Smyth; and I had every reason to be satisfied with the conduct of the Adjutant General, Major General Barnes, who was wounded, and of the Quarter Master General, Colonel De Lancey, who was killed by a cannon shot in the middle of the action. This officer is a serious loss to His Majesty's service, and to me at this moment.

I was likewise much indebted to the assistance of Lieut. Colonel Lord FitzRoy Somerset, who was severely wounded, and of the officers composing my personal Staff, who have suffered severely in this action. Lieut. Colonel the Hon. Sir Alexander Gordon, who has died of his wounds, was a most promising officer, and is a serious loss to His Majesty's service.

General Kruse, of the Nassau service, likewise conducted himself much to my satisfaction; as did General Tripp, commending the heavy brigade of cavalry, and General Vanhope, commanding a Brigade of infantry in the service of the King, of the Netherlands.

General Pozzo di Borgo, General Baron Vincent, General Muffling, and General Alava, were in the field during: the action, and rendered me every assistance in their power. Baron Vincent is wounded, but I hope not severely; and General Pozzo di Borgo received a contusion.

I should not do justice to my own feelings, or to Marshal Blücher and the Prussian army, if I did not attribute the successful result of this arduous day to the cordial and timely assistance I received from them. The operation of General Bülow upon the enemy's flank was a most decisive one; and, even if I had not found myself in a situation to make the attack which produced the final result, it would have forced the enemy to retire if his attacks should have failed, and would have prevented him from taking advantage of them if they should unfortunately have succeeded.

Since writing the above, I have received a report that Major General Sir William Ponsonby is killed; and, in announcing this intelligence to your Lordship, I have to add the expression of my grief for the fate of an officer who had already rendered very brilliant and important services, and was an ornament to his profession.

I send with this dispatch three eagles, taken by the troops in this action, which Major Percy will have the honor of laying at the feet of His Royal Highness. I beg leave to recommend him to your Lordship's protection.

I have the honor to be, &c.

WELLINGTON.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.