Date and place

- June 16th 1815 in Ligny (province of Namur, Wallonia, Belgium) and its immediate surroundings

Involved forces

- French "Northern Army" (less than 60,000 men) under the command of Emperor Napoleon I Bonaparte.

- Prussian army, known as the "Army of the Lower Rhine" (about 83,000 men) led by Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Bluecher, Fürst von Wahlstatt

Casualties and losses

- French army: from 7,000 to 12,000 killed or wounded.

- Prussian army: from 12,000 à 25,000 dead and injured, 8,000 deserters.

Aerial panoramic of the battlefield of Ligny

On June 16, 1815, at the Battle of Ligny (sometimes referred to as the Battle of Fleurus), Napoleon won the last victory of his career. This success, however, proved neither decisive nor even sufficient to prevent the Prussians from taking a decisive part in the final defeat of the Emperor two days later near Waterloo.

General situation

Seeing his peace offers unceremoniously rejected by the Allies after his return from exile on the island of Elba , Napoleon decided to take the offensive to prevent the junction of the Anglo-Dutch forces of Arthur Wellesley of Wellington and Prussian of Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

At the head of the hastily assembled "Armée du Nord" (Northern Army), he entered Belgium through Thuin (southwest of Charleroi) on March 15, 1815, intending to defeat his two enemies separately before they could make their junction. Wellington's troops were in fact stationed around Brussels , those of Bluecher in the surroundings of Namur. Napoleon therefore chose a route which took him straight halfway between these two cities.

The same day, after the capture of Charleroi, the Emperor entrusted Marshal Michel Ney approximately 25,000 men and sent him to seize, on the left of the French army, the crossroads of Quatre Bras . Napoleon thus intended to prevent the English from helping the Prussians to whom he turned in person with the rest of his forces. He intended to crush them.

The forces present

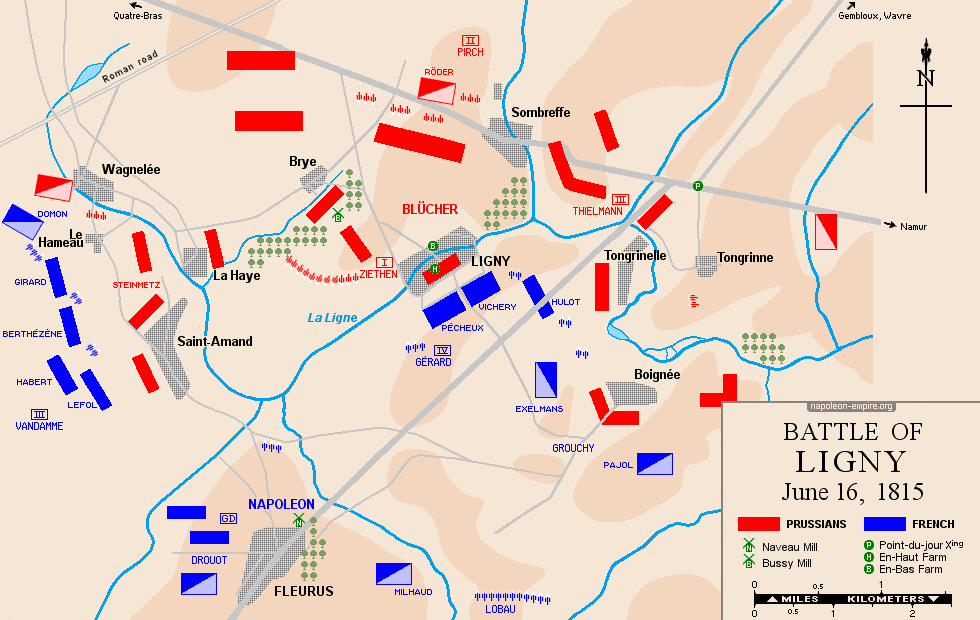

Napoleon had the III, IV and VI infantry corps, respectively under the orders of Dominique-Joseph-René Vandamme, Étienne Maurice Gérard and Georges Mouton de Lobau, of three cavalry corps commanded by Pierre Claude Pajol , Rémy Joseph Isidore Exelmans and Jean-Baptiste Milhaud and the Guard under the authority of Antoine Drouot .

The total strength did not exceed 60,000 men, because the army was far from being perfectly concentrated and many units were still stalling south of the river Sambre .

Blücher, for his part, could field Hans Ernst Karl von Ziethen 's I Corps, Johann von Thielmann 's III Corps and Georg Dubislav Ludwig von Pirch 's II Corps. The whole represented 83,000 men and 224 cannons.

Friedrich Wilhelm Bülow von Dennewitz ' IV Corps was several hours away and would not be able to arrive in time to take part in the fighting. This news, which fell during the night preceding the battle, provoked Homeric anger of the general in chief in his Headquarters, the presbytery of Sombreffe [50.52267, 4.59973].

It seems that poorly written or misunderstood orders — August Neidhardt von Gneisenau, Blücher's chief of staff, and Von Bülow cordially hating each other — were at the origin of this setback.

The terrain

The Prussians chose their position for its defensive capabilities. A stream, La Ligne, on which they relied from one end of the battlefield to the other, formed an obstacle likely to hinder the enemy without prohibiting counterattacks:

The village of Ligny was also carefully fortified. The streets were barricaded, access to bridges made impassable, the En-Haut farm to the south [50.51154, 4.57575] like that of En-Bas to the north [50.51345, 4.57460] transformed into bastions.

Blücher positioned Ziethen along the stream, in Wagnelée, La Haye [also known as Long-Pré], Saint Amand (brigade of Karl Friedrich Franciscus von Steinmetz ), Ligny , Sombreffe and Tongrinne; Thielmann was located between Sombreffe and Boignée; Pirch stood a little behind northwest of Sombreffe .

On the French side, Vandamme was placed to the west (left) facing Saint-Amand , while Gérard occupied the center in front of Ligny, which he looked at from the southeast . The cavalry was massed to the east (right). Emmanuel de Grouchy commanded it, with the exception of Milhaud's Corps, kept in the second line at Fleurus, just like the Guard and VI Corps.

Napoleon's plan called for a forceful assault on the Prussian right in order to push Blücher to send the reserves gathered in the center there. The French would then carry their main attack on it, which had become more fragile.

The fights

Napoleon arrived at Fleurus around 9:30 a.m., established an observatory at the Naveau mill [50.48554, 4.55536] and noted that Blücher had not moved from his positions the day before, on the Saint-Amand, Ligny, Sombreffe line. The Emperor decided to wait for Gérard's Corps before attacking. Gérard would reach around midday via the Fleurus road.

Blücher, after having consulted with Wellington around 1 p.m. at the Bussy mill [now disappeared] in Brye, near the farm of the same name , returned for his part determined to hold his position. He hoped that the Anglo-Dutch would send him a corps of 40,000 men to fall in flank on the French left wing. Wellesley had in fact allowed him to expect this intervention, unless he himself was taken to task.

The battle began around 2:30 or 3 p.m.: at the signal for the attack - three cannon shots fired at regular intervals by a battery of the Guard - the French III Corps immediately marched on Saint-Amand . Étienne Nicolas Lefol's division captured it in barely a quarter of an hour, despite strong resistance and a Prussian counterattack.

Half an hour later, the division of Jean-Baptiste Girard descended on the place named Le Hameau de Saint-Amand [also known as Beurre-sans-Croute] and on the hamlet of La Haye , which he took. There too, the Prussians defended themselves valiantly and led several counter-offensives.

French losses were high: more than a quarter of the division was out of action at 4 p.m. Its two brigades saw their generals fall, General Girard himself was mortally wounded at the farm of La Haye (he would succumb on the following June 27) and it is a colonel (Tiburce Sébastiani or Jean-François-de-Sales Matis, depending on the sources) who might take command.

In the center, around 3 p.m., Gérard launched three columns on Ligny. The first assaults, led by the division of Marc Nicolas Louis Pécheux, failed due to the superiority of the Prussian artillery. Once reinforced by two Guard batteries, Gerard's gunners could carry out sufficient preparation for the next attack to reach the southern bank of the Ligne.

This stream, which flew between two embankments, with its banks overgrown with willows and hedges lined with sniper riflemen, constituted a solid defense. Especially since behind it stood the farms of En-Haut and En-Bas, the Church, the castle and the houses of the village whose walls had been crenellated.

Fights of increasing fierceness took place in the town until 7 p.m., with varying fortunes swinging victory to one side or the other half a dozen times in the afternoon. All the testimonies emphasize the prodigious fury of the battles fought to cross the Ligne and take the two bridges upon it or seize fortified buildings.

Further east, on the French right wing, and until around 6 p.m., operations were not very sustained: a few skirmishes, a low-intensity artillery duel. Grouchy's mission essentially consisted of preventing the Prussians from stripping their left, which the mere presence of his troops, through the threat they posed on the road to Namur, was enough to ensure. The Prussians, in fact, could not allow themselves to be cut off from the corps of Von Bülow, whose arrival they were awaiting.

From 4 p.m., seeing his right wing in difficulty, Bluecher did not hesitate to successively mobilize all his infantry and cavalry reserves to reinforce it. Vandamme responded by engaging the division of Pierre Joseph Habert and that of the mounted hunters of General Jean-Siméon Domon , unused until then.

Around 6:30 p.m., Blücher made a final effort to crush the French left. The intensity of its artillery reached a maximum. At 7 p.m., Vandamme resigned himself to evacuating Saint-Amand and La Haye. However, with the reinforcement of a few battalions of the Young Guard under the command of Guillaume Philibert Duhesme , he managed to contain the enemy advance.

On the French right, around 6 p.m., Thielmann attacked on the Fleurus road. His offensive was quickly stopped, between Tongrinelle and Potriaux, by the divisions of Étienne Hulot de Mazerny and Antoine Maurin. The French then tried to break through the Prussian defenses. They crossed the Ligne, took Tongrinne and Tongrinelle, then Potriaux before being blocked in their turn.

At the same time, a liaison officer sent by Vandamme announced to the imperial general staff the arrival of an unknown column advancing towards Wagnelée from the direction of Villers-Pervin. The news caused confusion for a moment among the French high command. If they were enemies, they would fall on the already struggling III Corps.

Napoleon interrupted the establishment of his attack system on the opposing center and prepared to bring in Drouot and the remaining units of the Guard on the left wing.

Around 6:30 p.m., the new arrivals were identified. It was in fact the Corps of Jean-Baptiste Drouet d'Erlon, called to the rescue a few hours earlier by Napoleon although he was in principle at Ney's disposal. These 20,000 men, who appeared in the rear of the Prussians, would however receive no orders and would soon turn around, recalled by Michel Ney to Quatre Bras where they would arrive too late and would prove to be just as useless as at Ligny.

Napoleon, however, realized that Blücher had not only considerably weakened his center for the benefit of his right wing, but that he had also used up all his reserves to do so. The Emperor therefore decided that it was time to break it, as he had intended to do from the beginning. For this he had fresh and still intact troops: Lobau's VI Corps, Milhaud's IV Cavalry Corps and the Old Guard, around thirty thousand men in total.

The Prussians still stubbornly clung to a few strong points in Ligny: the castle of Looz [now disappeared], the En-Haut and En-Bas farms, the Church . From 7 p.m. onwards, they underwent artillery preparation of exceptional intensity carried out jointly by the batteries of the Guard and those of Gérard's corps, in all more than 100 pieces of cannon.

After which Gérard, with the Pécheux divisions and that of Louis Joseph Vichery , Milhaud’s cuirassiers and five regiments of the Old Guard on foot, mounted the assault. The village was attacked both from the southeast [current Ruelle du Curé] , from the west and from the center [current Rue des Généraux Gérard et Vandamme] where the En-Bas Farm soon fell into the hands of the French, who crossed the Ligne.

Napoleon, with the cavalry of the Guard, entered the town himself and settled at a place called La Tombe, on a mound [razed in 1885 to find a hypothetical treasure]. Once the village had been definitively conquered, the Guard climbed onto the Brye plateau where the enemy was attempting to reorganize.

On the Vandamme side, the III Corps, although tired, also went on the attack and chased the troops facing it in the direction of Ligny. Under cover of the growing darkness, the Prussians retreated, resisting as best they could. Some managed to regroup behind Brye .

Driven into the center, the Prussian army sought salvation in a cavalry charge that Blücher led in person in the vicinity of Saint-Amand. He almost got caught when his horse was killed.

At 8:30 p.m., the Prussian front was definitively dislocated. The Prussians were only thinking of losing ground, except on the French right wing where the fighting continued until late in the evening. Napoleon set up his headquarters at the Château de la Paix in Fleurus, and spent there the night from the 16th to the 17th .

Losses were heavy on both sides. According to the authors, they varied between 7,000 and 12,000 killed and wounded for the French, between 12,000 and 25,000 for the Prussians. Added to this, for the German camp, were 8,000 deserters. Most of them were soldiers from provinces recently annexed to Prussia, reluctant to be killed for their new masters.

Consequences

The defeat of the Prussians was less complete than Napoleon believed. Furthermore, until mid-morning on the 17th, the Emperor, despite Grouchy's requests, neglected to pursue them.

The vanquished therefore had every leisure to organize their retreat towards Wavre , turning northeast towards Gembloux at a location called “Carrefour du Point-du-jour” ("Dawn Crossroads") [50.52367, 4.62601]. This direction, judiciously chosen by General Von Gneisenau, in fact avoided distancing the Prussians from the Anglo-Dutch, one of the main goals of Napoleonic strategy, and would thereby prove decisive for the course of events.

When Grouchy finally received the order to pursue the enemy, with the corps of Vandamme and Gérard under his command as well as the cavalry of Pajol and Exelmans — in all 32,000 men and 96 cannons — he was further delayed by a violent storm which slowed down its progress.

In the evening, the Prussians gained an additional twenty kilometers lead over their pursuers and were ahead of them by more than forty. The fugitives were also joined in Wavre by the corps of Von Bülow, which had not participate in the fighting, and was therefore intact.

Blücher, despite his defeat on the 16th, was therefore ready, from the 17th, to intervene the next day in the battle that the Duke of Wellington was preparing to fight. The English generalissimo urged him to do so in dispatches written from his headquarters of Waterloo.

Map of the battle of Ligny

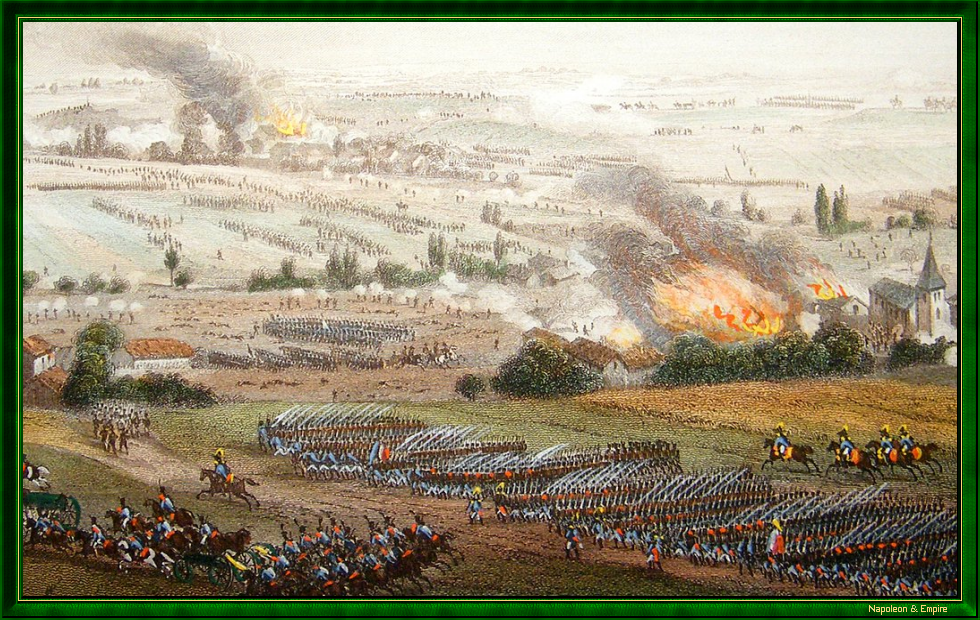

Picture - «The Battle of Ligny», watercolor by Théodore Yung (or Jung) (Strasbourg 1803 - Strasbourg 1865)

The day was marked by the useless marches and countermarches of Drouet d'Erlon's I Corps. In principle subordinate to Ney, he was however called by Napoleon during the battle in order to take the Prussians from the rear. But Marshal Ney, informed too late, had meanwhile recalled him, so that these 20,000 men were ultimately not engaged either at Ligny or Quatre Bras.

As indicated above, Marshal Blücher was almost taken prisoner towards the end of the battle when his horse was killed under him and it fell, pinned him to the ground near French soldiers... but they, in the semi-darkness and the agitation of the combat, passed by without seeing him . The old marshal was then able to free himself with the help of his aide-de-camp, Count August Ludwig Ferdinand von Nostitz-Rieneck, and rejoind his people on Sergeant Schneider's horse.Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Mr. Dominique Timmermans, who introduced us to this battlefield, the day before the bicentenary.Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.