Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power on 18 Brumaire Year VIII caused many royalists to entertain the false hope of a restoration. Some, like René de Chateaubriand, thought the return of the monarchy was impossible and joined a regime that was more acceptable to them than the Republic as it had been since 1792. Others wanted to believe Napoleon would quickly restore Louis XVIII to the throne. Chief among them was Louis XVIII himself. There was even some talk that Bonaparte would put Louis-Philippe d'Orléans on the throne, though even the pragmatic prince himself did not believe this.

Royal Illusions

Enlarge

In September 1800, the First Consul officially commented for the first time and with great clarity on these opinions. He succinctly responded to a letter from the Count de Provence who asked him to personally effect his restoration: "You should not hope to return to France. It would be better for you to march over one hundred thousand corpses."

Somehow, this was not enough to definitively dispel the illusions of Louis XVI's brother. A definitive end to the talks between Bonaparte and the Count took place two years later at the beginning of 1803. At this point, the French were pursuing, with some success, a poorly-conceived diplomatic policy where Prussia and Russia as intermediaries would persuade the Count de Lille to renounce his hereditary rights (this was the title the future Louis XVIII was using at the time while he was living in Warsaw with the financial support of the Tsar). The Count finally understood that he could not expect any help from Napoleon who he now considered a usurper. But through a cleaver calculation on his part, he was able to foil the French policy and consolidate his own position. In effect, he transformed Bonaparte's misguided initiative into a way to confirm his claim to the throne of France.

However, these hesitations only further weakened the royalist faction that had already lost its key leaders when they surrendered to the regime between the end of 1799 and the beginning of 1800. Suddenly, some of the leaders of the counter-revolution realized that in reality Bonaparte was the single greatest obstacle standing the way of the Restoration. Showing themselves to be more royalist than the King, they decided in 1800 to eliminate the First Consul.

The Assassination Attempt in the rue Saint-Nicaise

Georges Cadoudal and Jean-Guillaume Hyde de Neuville set the plot in motion. Cadoudal already had considerable military experience. He had commanded the Chouans in Brittany in 1793 and in 1799 and had participated in the landing at Quiberon in 1795. He had be made a Lieutenant General by the Count d'Artois. Hyde de Neuville, though a young man at 24, had distinguished himself by organizing a royalist demonstration in Paris on January 21, 1800 for the anniversary of the execution of Louis XVI. On that day, he and his friends had covered the façade of the Church of Sainte-Madeleine in black and posted the King's will on the door. Most of his accomplices were captured and shot but he managed to escape.

The two men began to stir up unrest in the country to distract the police from their real intentions. To this end, they organized the kidnapping of Senator Clément de Ris, which is occasionally falsely attributed to Joseph Fouché. These events provided Honoré de Balzac with the inspiration for his novel "Une ténébreuse affaire" ("A Murky Business"). The assassination of the constitutional bishop and regicide Yves-Marie Audrein on November 18, 1800 was probably also their doing.

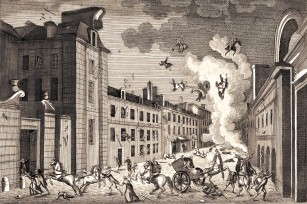

The true purpose of their plot was only revealed on December 24, 1800 in the rue Saint-Nicaise. That night, an infernal machine exploded Bonaparte's carriage had passed by on its way to the opera. The device was hidden in a barrel filled with gun power, flammable material and bullets. The explosion killed 22 people and injured hundreds of others, but left the First Consul and those with him untouched. Only one or two members of the Consular Guard were injured.

Despite Fouché's opinion to the contrary, the attack was at first attributed to the Jacobins, though not without ulterior motives. This allowed for the arbitrary deportation to the Seychelles of hundreds of Jacobins and for the dismissal of civil servants suspected of Jacobin sympathies and of those who were not supportive of the new regime. The investigation that followed did not fail to uncover that the true conspirators were Chouans working with Cadoudal and Hyde de Neuville. The two masterminds managed to evade capture. The agents responsible for constructing the bomb were not so lucky. Carbon and Saint-Réjeant were arrested, sentenced and finally executed on April 20, 1801.

The Calm Before the Storm

The next few years were marked by a relative calm inside France thanks to the Treaties of Lunéville, Paris and Amiens. The situation took a turn for the worse when the conflict was reignited. This became possible in 1803 despite the signing of the Treaty of Amiens that year. The difficulties involved in implementing this treaty did not augur well for a future of peace in Europe.

The counter-revolutionary groups set to work once again. First among them was the spy ring organized by the Count d'Antraigues. He provided his clients (mostly Russia and England) with sensitive information obtained in France from highly placed individuals such as the mysterious "Friend in Paris" whose identity is still unknown. This Friend, and his son after him, sent the Count the correspondence between the French ambassador in Saint Petersburg and the Ministry of External Relations, the plans for the naval campaign of 1805 (possibly making Admiral Nelson's task much easier) or the details regarding the size of the Grande Armée at the beginning of the German Campaign of 1805.

Since 1803, the First Consul had been demanding that the Elector of Saxony expel the Count d'Antraigues who was living in Dresden and, after a flat refusal, decided to have him kidnapped. This turned out to be impractical, so Bonaparte contented himself with publishing a set of Secret Memoires that defamed the conduct of the Count in Milan in 1797 in the hope of discrediting him.

Cadoudal's Conspiracy

Meanwhile, still in 1803, the plotting started again, probably spurred on by the Count d'Artois. Hyde de Neuville and Cadoudal, who had not abandoned their plot to assassinate Bonaparte, arrived in England at the beginning of the year to share their plan with the Count. This plan was to capture and kill Bonaparte before starting a general revolt led by a Bourbon prince in France to guarantee the throne for Louis XVIII. It is possible that the future king had talked of personally leading the revolt without fully committing to the idea.

Nonetheless, the intrigue began to gain momentum. It was decided that Bonaparte would be captured along the road to Saint-Cloud in Paris. Thanks to the one million pounds sterling from the British authorities, several Chouans moved to Paris. They were soon joined by Cadoudal on August 30, 1803 after landing in Normandy seven days earlier.

The French authorities were swiftly informed of his presence on French soil by a double agent, Jean Claude Hippolyte Méhée de la Touche. He had recently infiltrated the royalist network during an operation targeting the English intelligence services. He sent the police two letters that revealed Cadoudal's arrival in Paris and the immanent arrival in France of a Bourbon. Despite this information, the Chouan leader remained hidden, though not for lack of searching.

On January 16, 1804, it was Jean-Charles Pichegru's turn to secretly land in France. Among his companions was Jules de Polignac, who would be Prime Minister in 1830, but not the Count d'Artois to Cadoudal's great consternation. The preparations continued nonetheless.

On January 28, Cadoudal and Pichegru met with Moreau. Though Moreau passed himself off in public as a republican, he was more likely sympathetic to the royalist cause as was shown by his actions on numerous occasions in 1796, 1797 and 1803 and his attitude in 1813. His still stunning victory in the Battle of Hohenlinden and his growing hostility for the First Consul (made worse by his wife's jealousy for Joséphine de Beauharnais that was shared by her mother) attracted the attention of the royalist conspirators. But Moreau refused to participate in Bonaparte's elimination, though he admitted that he expected to replace him if he were to disappear. Since Moreau remained vague regarding his feelings toward to a possible Restoration, Cadoudal left exasperated and convinced that the general saw the situation as a way to further his personal ambitions.

The Disintegration of the Network

Soon after, the police captured two conspirators close to Cadoudal whose interrogation led to a wave of arrests. The meeting on January 29 was thus brought to the attention of the government. In light of this irrefutable proof, Bonaparte incarcerated Moreau in the Temple prison on February 15.

In the days that followed, almost all of the Chouans in Paris were hunted down and imprisoned. Cadoudal went on the run and once again evaded arrest. A law from February 27 made it a crime punishable by death to hide or help him and his accomplices. A wave of denunciations followed this announcement. Armand de Polignac was captured on February 29 followed by Jules on March 4. Five days later, Cadoudal was located, but he managed to escape by killing a police officer while they were trying to arrest him. A chase ensued, and he was finally captured near the carrefour de l'Odéon in Paris.

Sent to the Temple as well, it was not difficult for him to admit to planning the kidnapping of the First Consul. By contrast, he totally exonerated Moreau by accusing him of bearing the responsibility for the failure of the plot due to his dream of replacing the First Consul and his refusal to work toward the Restoration of Louis XVIII.

By the end of March, all of Cadoudal's co-conspirators were behind bars. On April 16, Pichegru was strangled in his cell. Whether it was suicide or an assassination to prevent him from revealing the names of other conspirators has never been established.

The Repression

The accused were judged by an extraordinary tribunal without jury or the possibility to appeal. The trial lasted from May 28 to June 10. Moreau was condemned to two years in prison. The lightness of the sentence infuriated Bonaparte and he commuted it to banishment for life. The victor of Hohenlinden was exiled to the United States. He did not return until 1813 when he advised the European armies massed against his country. He died close to the Battle of Dresden when he was mowed down by a French cannon ball.

Cadoudal, Armand de Polignac and 17 others were condemned to death. But the mobilization of many aristocrats who had already returned from exile on behalf of their fellows caused Bonaparte to grant a reprieve to all the condemned nobles. They had to wait in prison for the Restoration of 1814.

The common conspirators were guillotined on June 24.

The reversal of the death sentences caused shock waves throughout Europe, especially since it was accompanied by the news of the kidnapping and execution of the Duke d'Enghien.