Date and place

- August 26-27, 1813, Dresden, capital of Saxony, on the banks of the Elbe river (now in the German state of Saxony).

Involved forces

- French army (40,000 then 120,000 men) under the command of Marshal Laurent de Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, then Emperor Napoleon I.

- Russian-Austro-Prussian coalition (180,000 men) commanded by Field Marshal Karl Philipp Fürst zu Schwarzenberg.

Casualties and losses

- French army: around 10,000 dead or wounded.

- Russian-Austro-Prussian coalition: around 38,000 dead, wounded or prisoners, 40 cannons.

Aerial panorama of the battlefield of Dresden

The two-day Battle of Dresden was Napoleon I's last major victory in Germany. Clearly outnumbered, he scored a dazzling tactical victory, which he was unable to exploit.

General situation

The Pleiswitz armistice [Pläswitz, Pielaszkowice], signed after the battles of Lützen and Bautzen between France and the Russo-Prussian coalition, ended on August 10, 1813 with the failure of the mediation led by Austrian Chancellor Clemens von Metternich. Two days later, Austria joined the Allies and declared war on France.

Allied plan of action

The Allies organized three main armies: those of Bohemia, Silesia and the North, entrusted respectively to Prince Carl Philipp zu Schwarzenberg, General Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher and the Royal Prince of Sweden, former Field Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte.

The Bohemian army comprised 120,000 Austrians, 70,000 Russians and 60,000 Prussians. The Russians obeyed the orders of Mikhail Bogdanovich Barclay de Tolly (Михаи́л Богда́нович Баркла́й-де-То́лли), the Prussians those of Friedrich Kleist von Nollendorf ; the Prince of Schwarzenberg was commander-in-chief.

French force dispositions

The strategy adopted by the coalition forces was to gradually squeeze the French army into a circle small enough to allow the three allied masses to assault it in concert and overwhelm it with numbers. In the meantime, each of them must refuse to fight when confronted by Napoleon himself.

Napoleon had established his defensive line on the Elbe . Dresden, a city of some 60,000 inhabitants and capital of the Kingdom of Saxony, was the nerve center. His operational center was located there.

Upstream, the towns of Königstein (in der Sächsische Schweiz) and Lilienstein, on either side of the river, and the bridge linking them, commanded the outlets to the Bohemian mountains. Downstream, garrisons at Torgau, Wittenberg, Magdeburg and Hamburg held the Elbe crossings. A post was also improvised at Werben [Werben an der Elbe], as the distance between Hamburg and Magdeburg seemed too great.

Behind this first cordon, Napoleon distributed his forces in a way that perfectly matched the enemy's strategy, the broad outlines of which he had anticipated:

- The 30,000-strong XIV Corps, recently formed and entrusted to Marshal Laurent de Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, was stationed at Königstein, on the left bank of the Elbe, some 30 kilometers upstream from Dresden. They thus blocked the Peterswalde [Petrovice] road, where the enemy could emerge from Bohemia into Saxony to attack the French army's rear.

- Dominique-Joseph Vandamme, also commanding a 30,000-strong Corps, occupied the right bank of the river at Lilienstein, opposite Gouvion-Saint-Cyr. From there, he guarded the Bohemian crossings to Lusatia.

- In the same region, a little further east, the Corps of Józef Antoni Poniatowski and Claude-Victor Perrin (known as Victor), guarded the Zittau defile, another breach in the Bohemian mountains.

If the enemy broke through on the Peterswalde road, all arrangements were made for Marshal Gouvion-Saint-Cyr to slow down the advance before locking himself into the entrenched camp established at Dresden. His forces, combined with the city's garrison, seemed sufficient to hold out long enough for help to arrive.

Initial battles against the Silesian army

In the days leading up to the battle, Napoleon inspected the positions of Gouvion-Saint-Cyr and Vandamme, then moved further east. He penetrated Bohemia for a while to assess Schwarzenberg's intentions, and deduced from his movements that Schwarzenberg was preparing either to capture Dresden or to march on Leipzig to place himself between the French army and the Rhine.

Nevertheless, before returning to fight the Bohemian army, the Emperor intended to neutralize the Silesian army, at least temporarily. This was almost achieved on August 22, when a letter from Gouvion-Saint-Cyr informed him that the Army of the Danube had arrived, arriving as expected at Peterswalde. Napoleon immediately organized to take advantage of the movement he had anticipated.

The Guard set off for Dresden. Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont's Corps accompanied it, as did a large part of Victor de Faÿ de La Tour-Maubourg's cavalry. Vandamme and Victor were ordered to retreat to the Elbe. This meant that 180,000 men would have reached Dresden within the next four days, including at least 80,000 during the first two.

On the 23rd, Napoleon had no worries about the fate of the city, as he finished pushing Blücher back as far as possible beyond the Katzbach [Kaczawa] river, at Jauer [Jawor]. In the middle of the day, the Emperor left for Görlitz. There he learned that the population and authorities of Dresden, including the King of Saxony and the generals in charge of defense, were alarmed by the immensity of the Allied forces threatening them. The heights around the city, on the left bank of the Elbe, were said to be covered with them. Napoleon sent Joachim Murat to assess the situation.

The coalition troops in front of Dresden

The four columns of the Bohemian army, commanded respectively by Johann Joseph Cajetan von Klenau und Janowitz , Ignáz Gyulai von Máros-Németh und Nádaska (often called Giulay in French texts), Kleist and Piotr Khristyanovitch Wittgenstein (Пётр Христианович Витгенштейн), had just entered Saxony by four different routes.

Wittgenstein's column was the first to arrive. General Michel Marie Claparède 's 43rd Division, in the vanguard on the Peterswalde road, fought hard for the Berggiesshübel plateau before retreating.

On August 23, Gouvion-Saint-Cyr withdrew to Dresden. He had previously entrusted the 42nd Division with the defense of the Koenigstein and Lilienstein forts, the bridge over the Elbe linking them and the posts along the river. In so doing, he prevented the enemy from crossing the river.

Still convinced that the city could withstand an assault for several days, Napoleon devised a new maneuver. He expected nothing less than to seize the entire Bohemian army and the sovereigns it harbored (the King of Prussia and the Tsar of Russia), arriving behind the Allies' backs via Lilenstein and Koenigstein, to trap them between Dresden and himself.

But in the city itself, the sight of the surrounding heights covered with enemy troops was increasingly disturbing. Messenger after messenger were sent to ask Napoleon to bring back all his reserves to repel the assault. Murat himself could only observe the presence of an innumerable army, seemingly determined to attack.

Gourgaud's report and Napoleon's change of heart

In response to a letter from Napoleon reminding him of the means at his disposal to resist, Marshal Gouvion-Saint-Cyr simply replied that he would do his utmost, but could not guarantee anything. Napoleon was irritated by this excessive circumspection. On the 24th, he sent to Dresden an officer, Gaspard Gourgaud, to examine the situation in depth, with order to hurry back and make his report.

On his return, in the evening of the 25th, Gourgaud drew such a calamitous picture of the state of affairs that Napoleon altered his plans to rush to the city's aid.

Procrastination on the part of the coalition forces

By the 25th, three of the four Allied columns were already assembled on the heights of Dresden. Only Klenau, whose route was the longest, has'nt arrived yet. At the headquarters of the Tsar and Prince of Schwarzenberg, at Nöthnitz Castle [51.00362, 13.73009] in Bannewitz, Antoine Jomini (who had gone over to Russian service during the armistice) and the boldest advisors to Tsar Alexander I of Russia (Александр I Павлович Романов), knowing Napoleon to be absent, were preaching an immediate attack on Gouvion-Saint-Cyr's divisions, still deployed on the plain in front of the city.

Jean-Victor Moreau (recently returned from America to advise the Tsar) disagreed. The Prince of Schwarzenberg closed the discussion by indicating that he would not act in any case before the arrival of his fourth column, scheduled for the following day.

Napoleon's new plan

Napoleon, for his part, came up with a new combination that was less promising but safer, and still attractive. He was going to send the 40,000 men of Vandamme's Corps to Königstein, while he moved on to Dresden with 100,000 others. With the city thus saved, he was confident of defeating the nearby coalition forces.

Once the latter have been defeated, Vandamme, who will in the meantime have made himself master of the Pirna camp and the Peterswalde road, will fall upon their rear to decimate or capture them. As for those who would managed to evade him, their retreat promised to be most arduous on the bad roads they would have to take.

Once the decision had been taken, Napoleon immediately sent the Old Guard, already in the vicinity of Stolpen, Latour-Maubourg's cavalry and half of general François Antoine Teste 's division positioned on the banks of the Elbe to Dresden. The Jeune Garde and Marmont's Corps, which had been heading for Lowenberg [Lwówek Śląski] since the 23rd, received the same order, as did Victor's Corps en route to Koenigstein from Zittau.

Napoleon ordered them all to march through the night, to be in position at dawn behind Marshal Gouvion-Saint-Cyr's Corps. Vandamme was also given new instructions: to cross the bridge between Lilienstein and Koenigstein with his 40,000 men, take the Pirna camp and block the Peterswalde causeway. The Emperor himself set off after a short rest, arriving in Dresden at 9 a.m. on August 26, where his arrival was greeted with enthusiasm.

After visiting and reassuring King Frederick August I of Saxony (Friedrich August I.) , he joined Marshal Gouvion-Saint-Cyr in front of the city.

Organization of the defense

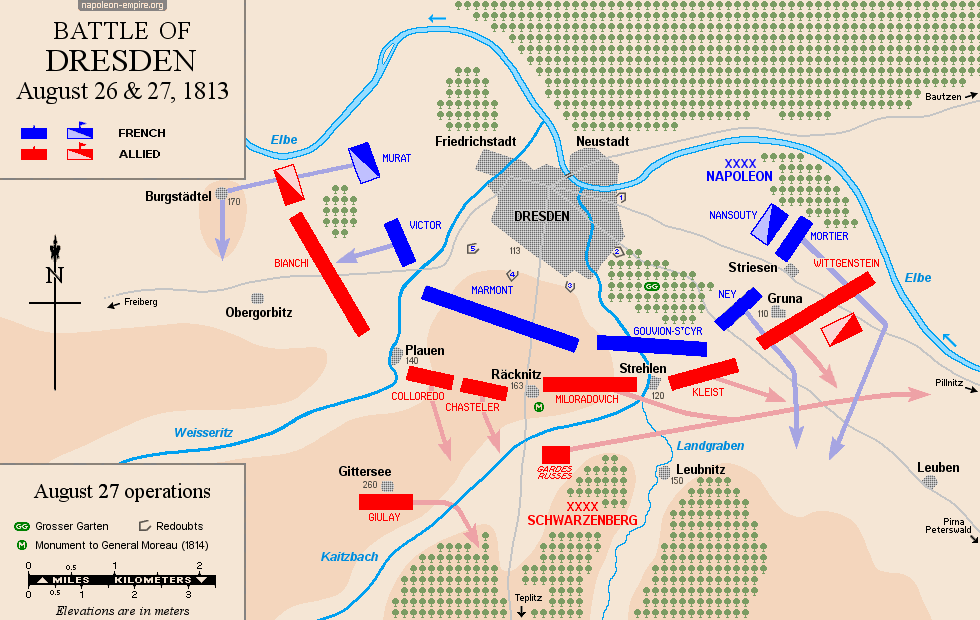

A series of hills dominated the part of Dresden on the left bank of the Elbe. The coalition troops held all these heights. The French defense system formed a semicircle, touching the Elbe at each end, east to the suburb of Pirna, west to Friedrichstadt. It was composed of several lines.

The first line, the outermost, comprised five redoubts. From the French left to right (i.e. east to west), the first redoubt was in front of the Ziegel [Ziegelschlag] octroi [51.05361, 13.75796].

The second redoubt was located in front of the Pirna road octroi [Pirnaer Schlag] [51.04567, 13.74961].

A third redoubt, at the southern end of the garden of the Moczinski Palace [Moszinska Palace], at the Dohna octroi [Dohnaer Schlag] [51.03940, 13.73845] protected the gate of the same name. Between the second and third redoubts flew the Kaitzbach, a canalized stream:

The fourth and largest redoubt was located [51.04244, 13.72570] between the Blinder [Blinder Schlag] and Falken [Falkenschlag] octrois.

Finally, the fifth, and westernmost, was in front of the Freiberg gate [Freiberg Schlag] [51.04792, 13.71894].

Fences and abatis linked these redoubts together. Behind came the old enclosure, consisting of a ditch and palisades. Barricades, closing off the street heads, completed the layout.

Depending on the disposition of the Allies on the heights, the Austrians were expected to attack between the Freiberg (south-west) and Dippoldiswalde (south) barriers [Schläge], the Prussians directly on the Gross-Garten [Großer Garten] , a public garden stretching over a kilometer wide and two to two-and-a-half kilometers long, and the Russians between it and the Elbe.

It was on the first line, known as the "entrenched camp", that Gouvion-Saint-Cyr set up his troops. The 45th Division held the first half, from the suburb of Friedrichstadt to the Dippoldiswalde barrier; the 43rd Division occupied the second half, as far as the suburb of Pirna.

In front of the latter, the Gross-Garten. General Pierre Berthezène 's 44th Division had moved in, with the bulk of its troops as close to the suburb as possible, so as not to distance it too far from the enclosure. The rest of the troops were divided between small posts, scattered around the outer garden to provide mutual support.

Between the redoubts, whose fires did not overlap sufficiently, Marshal Gouvion-Saint-Cyr distributed harnessed artillery to overcome this drawback.

Napoleon approved these preparations after inspecting them under fire from enemy skirmishers. He then supplemented them with the units at his disposal, namely the cuirassiers who had already arrived and the Vieille Garde, which was close behind. The Young Guard was not due to appear until the very end of the day, and Marmont and Victor's troops even later.

Until then, Napoleon decided to install Latour-Maubourg's cavalry, under Murat's command, in front of the Faubourg de Friedrichstadt, to the right of the 45th Division, and to support it with a brigade from General Teste, previously positioned on the Elbe.

In the center, he strengthened the link between the 45th and 43rd divisions with Westphalians drawn from the city garrison. Lastly, he employed part of the Old Guard to guard the various barriers in order to intervene in desperation, while the rest stood with him in Dresden's main square, waiting for events to unfold.

First day of fighting in Dresden: August 26, 1813

Passivity of the Coalitionists

Although the enemy could only hope to take the city by attacking it with the utmost vigor, they had not yet undertaken any large-scale action by mid-day. The only skirmishes were between the skirmishers of the 44th division and the Prussians.

This strange passivity stemmed from internal differences within the coalition staff. Moreau, the Tsar and even Jomini now wanted to abandon all offensive ideas and settle the army on the Dippoldiswalde heights. In their view, Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, now withdrawn to his entrenched camp, no longer seemed as easy to beat as he had been the day before, deployed on the plain. As Napoleon had probably not left him without resources, the 5,000 or 10,000 men that the assault would cost the coalition would be wasted. It was better to take up a secure position while remaining threatening.

But Frederick William III, King of Prussia, didn't see it that way. He objected that not to attempt anything after the bold move that had brought them to Napoleon's rear would be as timid as it would be inconsistent, and would also offend the patriotism of his soldiers.

If Jomini and Moreau were not shaken by these arguments, the Tsar seemed undecided when suddenly the almost simultaneous announcements of Napoleon's presence in Dresden and the rapidly approaching masses of the French army settled the issue. Retreat to Dippoldiswalde was imperative.

But the Prince of Schwarzenberg argued that such a move was not so simple to envisage. In his opinion, the last column to arrive would be in real danger if they were to withdraw prematurely, as they would have to cover the longest distance, with several valleys to cross. So it had to hurry slowly. However, any attack plans should also be cancelled.

Fighting beginning: advantage to the coalition

The order to make a strong demonstration on Dresden had already been issued, and the counter-order did not come quickly enough. At three o'clock, the coalition troops finally came to life, and a violent cannonade was unleashed, much to the surprise of the Tsar and the King of Prussia. With the entire army on the move, it became impossible to stop it, and the attack spread to the entire outskirts of the city.

As anticipated by the French, Wittgenstein's Russian Corps advanced between the Elbe and Gross-Garten. It came up against the 43rd Division as it crossed the Land-Graben, a large tributary stream of the Elbe. Caught in the crossfire from the first and second redoubts, the artillery on the other bank of the Elbe and the mobile batteries planned by Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, the Russians struggled to make headway. However, they managed to cross the river and continued to gain ground.

Their advance was facilitated by the success of Kleist's Prussians in the Gross-Garten itself. With a considerable numerical superiority (25,000 against the 6 or 7,000 French of the 43rd division), they soon seized the park, which their opponents preferred to abandon rather than risk being cut off from the town. This retreat was carried out methodically between the Pirna and Dohna barriers, and ended at Prince Antoine's gardens, just before the Pirna suburb. The 43rd division linked up with the 45th, which defended the rest of the enclosure.

The Austrians, for their part, attacked the third and fourth redoubts in the center. They subjected each of them to the fire of fifty cannons, as well as to an intense fusillade. The third redoubt, that of the Moczinski garden, could not hold out and had to be evacuated by its defenders. The Austrians seized it, then prepared to redouble their efforts on the fourth and to attack the fifth.

Such was the situation around five o'clock in the afternoon. The French position was so compromised that General Louis Friant , commander of the grenadiers of the Vieille Garde, brought several companies of this corps up to the line, despite orders to spare them. Living up to their reputation, these elite units crossed the Pilnitz and Pirna barriers, repelling the Russian column heads with fire and bayonets. At the Freiberg gate, the riflemen of the Guard followed suit, knocking the Austrian attackers off their feet.

Arrival of French reinforcements: the battle changed its face

While the Old Guard distinguished itself, the Young Guard entered Dresden. Four divisions of between 8,000 and 9,000 men immediately took to the line, the 1st and 2nd commanded by Marshal Adolphe Édouard Casimir Joseph Mortier, the 3rd and 4th by Marshal Michel Ney. Napoleon assigned the Pierre Dumoustier (1st) and Pierre Barrois (2nd) divisions to the Pirna barrier, where the Prussians were beginning to link up with the Austrians after conquering the Gross-Garten; the Pierre Decouz (3rd) and François Roguet (4th) divisions headed for the Pilnitz barrier to confront the Russians.

At the same time, Murat, who had just been joined by General Teste and his infantry, was ordered to charge the plain in front of Friedrichstadt with all his forces.

These new arrangements reversed the course of the battle. The Russians, initially blocked, were soon overrun by the columns of the 3rd and 4th divisions and driven back over the Land-Graben, which they crossed again in disorder. One of the divisions then pressed its right to bayonet Prince Antoine's garden, which was under Prussian attack. It then joined forces with the 43rd and 44th divisions to recapture the third redoubt, attacking it simultaneously from three sides. Six hundred Austrians were captured.

On the extreme French right, General Teste, who had come out of the Freiberg gate with his brigade behind Murat, captured the village of Klein-Hambourg. Ahead of him, Murat and his 12,000 cavalry forced the Austrians to return to the heights from which they had descended on the Friedrichstadt plain.

The day's outcome and the French plan of attack for the following day

Faced with this reversal of fortune, the Coalitionists decided to retreat, leaving 3,000 to 4,000 dead and wounded on the field, as well as 2,000 prisoners. The French lost only around 2,000 men.

Napoleon was very satisfied with the day's results, and had even higher hopes for the following day, convinced that the Allies could not rest on this failure without trying to repair it. With the additional 40,000 men he was expecting (Victor's II Corps and Marmont's VI Corps), he believed he could achieve a decisive victory. Examining the enemy positions on the evening of the 26th, from the top of a city bell tower where he had already climbed several times in the afternoon, he conceived a maneuver whose most dazzling results he anticipated.

Napoleon had noticed that most of the Austrian troops to the left of the coalition troops were separated from the main army by a deep gorge, at the bottom of which flew the Weisseritz river , a tributary of the Elbe whose mouth lay between Dresden and the suburb of Friedrichstadt.

Thus positioned, these units could expect no help from the rest of the Allied forces. What's more, the terrain on which they were standing also seemed to be the most favorable for cavalry movements. The Emperor therefore decided to join Victor's Corps to Murat's, and to rush them against the Austrian extreme left, which, isolated by the Plauen valley [Plauensche Grund is the name given to the Weisseritz gorges], would sink into it.

With the Allies' left destroyed, Ney, with the entire Young Guard, would attack their right en masse, pushing it back onto the heights from which it had descended. As a further consequence of these movements, the Allies lost the possibility of using the Freiberg road for their retreat, and had to use the Peterswalde road, which Vandamme locked up with 40,000 men. The enemy would then have no choice but to flee to Bohemia along the bad roads, where his pursuers would inflict considerable damage.

Having conceived this plan, Napoleon immediately set about carrying it out:

- General Teste was placed under the command of Marshal Victor, himself subordinate to Joachim Murat. Murat had 20,000 infantrymen and 12,000 cavalrymen at his disposal to carry out the Emperor's mission: to turn the Austrians to their left and throw them into the Plauen valley.

- Marshal Marmont's VI Corps set up in the center at the Dippoldiswalde barrier, in front of the Old Guard and the artillery reserve. The three divisions of Gouvion-Saint-Cyr's XIV Corps formed a tight column between the Dippoldiswalde and Dohna barriers. His right linked up with Marmont, his left with Gross-Garten. Napoleon informed his subordinates that he would remain in the center, and that the VI and XIV Corps would receive their instructions directly from him in the field.

- Marshal Ney, with the entire Young Guard and part of the cavalry, commanded by Etienne-Marie-Antoine-Champion de Nansouty , was tasked with driving the Russians from the plain between Striesen and Döbritz, and returning them to the heights once the coalition left had been routed.

- The redoubts, particularly those in the center, were re-equipped and reinforced, both in terms of personnel and firepower.

- Finally, in addition to the batteries of the Corps de Marmont and Gouvion-Saint-Cyr, he had more than a hundred guard cannons installed in the center, in anticipation of an intense artillery duel.

While his two wings took the offensive, the Emperor intended to remain immobile in the center with 50,000 men, reserving the right to intervene when events require. In the meantime, surrounded by his marshals, he spent the evening with the King of Saxony. Displaying a remarkable spirit, he was not afraid to announce to his host a battle that would be as decisive as it would be victorious the following day.

Allied preparations

The Allies were far less serene. They hesitated between the risk of another costly failure by renewing their attack, and the need to avoid giving their setback the character of a real defeat by withdrawing to the flanks of the Bohemian mountains, as Moreau had advised the day before. For lack of anything better to do, the decision was made to stay on the hillsides, which provided an excellent position.

By allowing the French to take the initiative, the allies intended to have a solid base from which to resist them before driving them back to the outskirts of Dresden. The danger represented by the Plauen valley did not strike anyone. The Prince of Schwarzenberg even weakened the troops operating beyond it by taking units from it to strengthen his center. In truth, he was counting on the arrival of the rest of the Klenau Corps to compensate for this drain.

These expected reinforcements did indeed arrive during the night, so that the following day, 120,000 French and Westphalians faced 180,000 coalition troops. Added to this were the 20,000 Russians of Prince Eugène de Wurtemberg (Eugen Friedrich Karl Paul Ludwig von Württemberg) , positioned in front of Pirna, and the 40,000 Frenchmen of Vandamme's I Corps, who were preparing to attack.

Second day of fighting in Dresden: August 27, 1813

Belligerent positions and initial French movements

On the morning of August 27, the weather was bad: rain and fog, which did not displease Napoleon, whose troop movements were concealed by the bad weather:

- General Teste established himself in front of the village of Lödbda, at the entrance to the Plauen valley, from which the Austrian grenadiers of General Vincenzo Federico Bianchi (Vinzenz Ferrerius Friedrich Freiherr von Bianchi) had emerged the previous day.

- Marshal Victor, with his three divisions, waited for Murat and Latour-Maubourg's cavalry, who had left at dawn, to turn the Austrian left through Priesnitz [Briesnitz].

- In the center, Marmont ranged himself at the foot of the Räcknitz heights.

- To his left, Gouvion-Saint-Cyr prepared to attack the Strehlen hills, setting up in front of the Gross-Garten.

- On the far left, Ney, the Young Guard and Nansouty's cavalry took up positions facing the Russians between Gruna and Döbritz.

- Napoleon placed himself at the Dohna barrier.

The Allies made only minor changes to their positions:

Wittgenstein, on the far right, stood with most of the Russian troops between the villages of Prohlis and Leubnitz. Only his vanguard had moved down to the plain, while the bulk of his forces were on the heights.

He had Grand Duke Konstantin (Великий князь Константи́н Па́влович) and the cavalry of the Russian Guard on his right, and Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich's (Михаил Андреевич Милорадович) grenadiers on his left, towards Klein-Pestitz [Kleinpestitz].

Kleist's Prussians completed the Allied left wing between Leubnitz and Räcknitz. They too have set up their vanguard on the plain, not far from Strehlen.

As for the Prussian guard, it took up position a little further back. Both Russians and Prussians obeyed Barclay de Tolly. Then, in the center, the Austrian divisions of Count Hieronymus Karl von Colloredo-Mansfeld and Jean-Gabriel-Joseph-Albert du Chasteler de Courcelles , spread out from Räcknitz to Plauen [Altplauen] .

The Tsar settled in the first of these villages, accompanied by Moreau. From his vantage point, he could almost see Napoleon.

The left was under direct Austrian control:

Bianchi's grenadiers, detached from Gyulai's Corps, occupied the ground east of the Plauen ravine, towards Gittersee [51.00650, 13.69695], ahead of the Austrian reserves commanded by Prince Frederick Joseph Ludwig Carl August of Hesse-Homburg (future Frederick VI) .

The remainder of Gyulai's Corps was held at Töltschen, west of the Plauen Gorge.

On his left, the infantry division of Alois Gonzaga Joseph Franz de Paula Theodor von Liechtenstein , at Rosthal [Roßthal] [51.03088, 13.67392] and Corbitz [Altgorbitz / Obergorbitz] [51.03737, 13.66995].

Then, further to the left, Joseph Mesko von Felso-Kubiny's division, the vanguard of the Klenau Corps, between Comptitz [Altgompitz] [51.044235, 13.64013] and Altfranken [51.03408, 13.64585].

Resumption of fighting: French wing offensives

The cannonade began as soon as the fog lifted a little. The large number of cannons on the battlefield (around 1,200) immediately gave it a strong intensity.

Soon, on the right, General Teste expelled the Austrian skirmishers from the village of Löbda, and advanced to the mouth of the Plauen valley. Marshal Victor formed his troops into columns, which climbed the heights to capture the villages of Töltschen, Rosthal and Corbitz. Finally, Murat galloped with his sixty squadrons to the right (west) of the Freiberg causeway. This movement was completed at around 10.30 am.

In the center, Gouvion-Saint-Cyr dislodged the Prussians from the village of Strehlen, then set off in pursuit towards the heights of Leubnitz. But the Prussians rallied, and a violent engagement began. Ney deployed between Gruna and Döbritz, then advanced on Reick with 36,000 men and five or six thousand horses, driving back Wittgenstein.

These maneuvers on the wings lasted until around eleven o'clock, while the battle was almost reduced to cannonade, with the exception of the fighting of the Gouvion-Saint-Cyr's Corps.

The Coalitionists were especially worried about Ney's march, as they had no idea what was happening on their left beyond the Plauen valley, which the terrain made invisible. Jomini suggested blocking Ney, once he had reached the village of Prohlis, by employing Barclay de Tolly's Russian reserves, and simultaneously striking his right flank by throwing the mass of Prussian corps against it. The Tsar supported this suggestion, Schwarzenberg accepted it, the Prussians loved it, and the order was passed on to Barclay.

Murat and Victor's attack

Around eleven-thirty, after careful coordination, Victor and Murat attacked.

Victor sent the Jean-Louis Dubreton division on his left, with the aim for the Jean Antoine Brun brigade to capture Töltschen from Nikolaus Joseph Rochus Ungnad von Weissenwolf's grenadiers, and for the Jacques (or Joseph) Martin Madeleine Ferrière brigade to take Rosthal from the Aloïs Liechtenstein division. On his right, he marched the single brigade of the François Marie Dufour division on the village of Corbitz, where the rest of the Aloïs Liechtenstein division was held. He kept the Honoré Vial division in reserve.

Murat, for his part, after having turned the Mesko division on the Austrian extreme left, advancing from Priesnitz to the village of Comptitz via Burgstädtel [51.05639, 13.66167], in turn moved on these same three villages at Victor's signal.

Despite the intensity of the artillery and musketry fire that greeted them, the young French soldiers, well supported, entered Töltschen and Rosthal in force and quickly overran them. Corbitz also fell, leaving two thousand prisoners in the hands of the attackers.

Liechtenstein, while withdrawing, noticed that a gap had opened up between the Dubreton and Dufour divisions. He tried to slip through. The Vial division, held in reserve until then, moved up to block his path, while Murat threw Étienne Tardif de Pommeroux de Bordesoulle's heavy cavalry division against the Austrian infantry.

The squares they formed were immediately ripped apart, the torrential rain rendering their fire ineffective. The survivors were pushed back by successive charges on the ridges between Altfranken and Pesterwitz, before driving on to Potschappel, at the bottom of the Plauen defile.

Meanwhile, the Dufour division resumed its march along the Freiberg causeway, while the Dubreton division drove Weissenwolf's grenadiers back into the Weisseritz, at the bottom of the Plauen chasm. As for Murat, he harassed the Meszko division to prevent it from joining forces with Aloïs Liechtenstein's division. After undergoing many charges in their retreat towards Compitz [Gompitz], to which they too had only their bayonets to oppose, due to the torrential rain, the six to eight thousand men it still comprised, totally encircled by the French cavalry, finally laid down their arms.

It was now two o'clock. On their left flank, the Allies had already lost over fifteen thousand men (four or five thousand dead and wounded, twelve thousand prisoners) and thirty guns. In practice, this wing no longer existed.

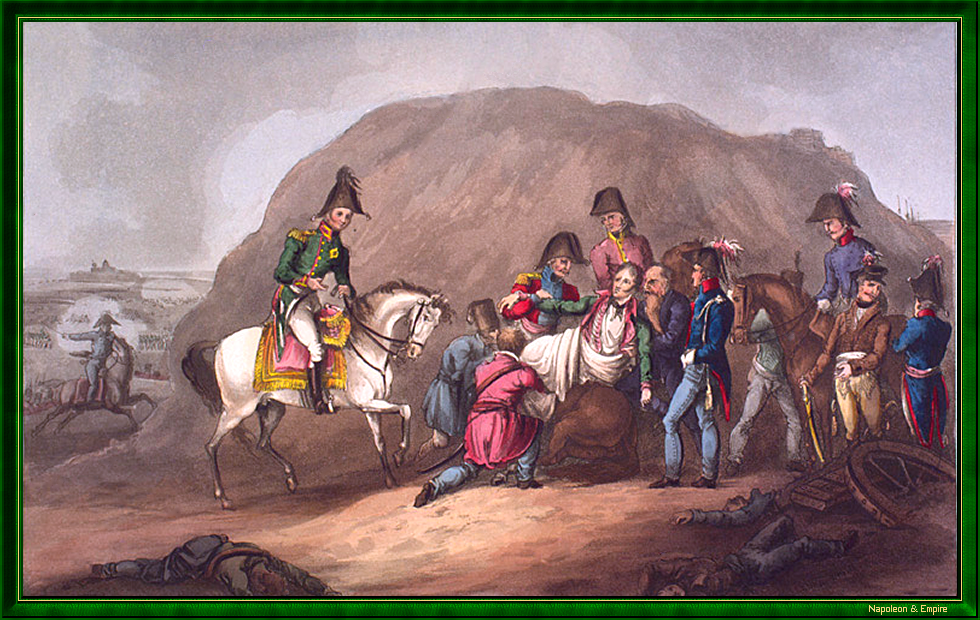

Moreau's death and other Allied misfortunes

In the center, operations consisted essentially of an artillery duel. Not considering it violent enough, Napoleon added thirty-two 12-guard pieces, commanded by Colonel Charles Pierre Lubin Griois , and had them advance as close as possible to their target, without fear of exposing himself to the enemy's cannonballs.

Just across the road, in Räcknitz, the enemy headquarters came within range of his fire. General Moreau recognized this and urged Tsar Alexander to retreat. But no sooner had he uttered his warning than he himself was hit in the legs, and very seriously.

This misfortune darkened the morale of Alexander I, the command and even the entire Allied army when the news spread. The news of the left wing's disaster was soon added to, followed by Barclay's refusal to carry out the prescribed maneuver against Ney, and finally the loss of the Pirna camp, taken by Vandamme.

The coalition generals consulted each other. No help could be sent to the left because of the Plauen Gorge. On the right, Barclay's arguments for staying put appeared sound: to move his artillery over terrain criss-crossed by canals in such appalling weather would effectively be to sacrifice it. As a result, this wing was in danger of being overwhelmed by Ney, who was advancing unopposed from Reick towards Prohlis. Finally, the Peterswalde road could fall to Vandamme at any moment.

Some daring men were determined to continue the fight. But Schwarzenberg didn't care. He had already lost twenty thousand men, his ammunition convoys were not arriving, Murat was caracoling in his rear, and God knew what fate awaited the fraction of the Klenau Corps that had not yet joined him. As General-in-Chief, Schwarzenberg categorically refused to be stubborn. The order to retreat was given without any precise indication of the route to be followed by each column. Only the principle of a withdrawal to the Bohemian mountains was accepted.

Allied retreat

The Allied army withdrew. It could soon be seen passing over the crest of the hills above Dresden. On the left (east), Gouvion-Saint-Cyr and Ney set off in pursuit of the Russians; on the right (west), Murat, following the road to Freiberg, accumulated prisoners and captured baggage and artillery.

By six o'clock, the battle was over.

At sunset, Napoleon returned to Dresden, where he was enthusiastically welcomed first by the population, then by the King of Saxony, all equally relieved at no longer having to fear an assault on the city. In the evening, he gave the order for the army Corps, after a night's rest, to set off in pursuit of the enemy at dawn.

In the coalition camp, once they had reached the summit of the heights above Dresden, they began to discuss the direction the retreat should take. Some wanted to retreat no further than the foothills of the Bohemian mountains. Others wanted to take cover beyond the Eger [Ohře] river, deep inside Austrian territory. This was the opinion of Generalissimo Schwarzenberg in particular. Without deciding how far back they would go, they at least decided to go back over the mountains.

The question was which way to go. The Peterswalde route, with Vandamme's presence in Pirna, was certainly perilous, but using the secondary roads, which were not very practicable, would undoubtedly cause problematic congestion. What's more, using them would mean abandoning Prince Eugène de Wurtemberg, who had been dislodged by Vandamme, and Count Alexander Ivanovich Ostermann-Tolstoy (Александр Иванович Остерман-Толсто́й) , who had been sent to his rescue.

Finally, it was agreed that Barclay, with the bulk of the Russians, would take the Peterswalde road and reopen it if necessary; that the Prussians and part of the Austrians would follow in reverse the route by which the second column had arrived − namely Altenberg, Zinnwald, Teplitz [Teplice] − ; that the rest of the Austrians would move up the Freiberg causeway via Komotau [Chomutov]; that all these movements would begin very early the following day (August 28), to reach the entrance to the mountains before the enemy was on their heels.

On August 28, these arrangements were implemented, and the three columns set off, not without apprehension as to the future course of a campaign that had got off to such a poor start.

Results

The coalition troops left ten to fourteen thousand dead and fifteen to sixteen thousand prisoners. They also lost some forty cannons. On the French side, eight to nine thousand men were put out of action, most of them by the artillery. Delighted, Napoleon promised himself further satisfaction in the days to come, thinking of Vandamme's Corps and its 40,000 soldiers, ready to fall on the retreating enemy's rear.

Consequences

At the end of the Battle of Dresden, which proved to be one of their worst routs in terms of the numbers involved, the morale of the coalition troops plummeted. They were not far from fearing that the successes of the previous year had been a mere accident unlikely to be repeated. And their outlook is indeed rather gloomy.

But the following days saw a succession of French defeats, conceded by Napoleon's lieutenants: at Kulm on August 30 (Vandamme), then at Dennewitz (Ney) on September 6. In addition to the losses already suffered by Nicolas Oudinot at Gross-Beeren (August 23) and Étienne Macdonald at Katzbach (August 26), they totally cancelled out the effect of the Battle of Dresden and restored the Allies' situation and fighting spirit.

Map of the battle of Dresden

Picture - "The death of Moreau, before Dresden, August 1813". Designed by William Heath (1795-1840), colored by Thomas Sutherland (1785-?).

Napoleon, who had seen that one of his cannonballs had fallen into the hands of the highest dignitaries in the Allied army, wondered on his way back to Dresden, and kept asking everyone around him: "Who did we kill in this brilliant squadron? The first clue came during the evening, when the collar of a dog found in the hut where Moreau had received first aid was brought to him. It read: "I belong to General Moreau.

French order of battle

| Old Guard | 1st Infantry Division of the Old Guard | General Friant | |

| Guard Cavalry | General Nansouty | 1st Guards Cavalry Division | General Ornano |

| 2nd Guards Cavalry Division | General Lefebvre-Desnouettes | ||

| 3rd Guards Cavalry Division | General Walther | ||

| I Corps of the Young Guard | Marshal Mortier | 1st Infantry Division of the Young Guard | General Dumoustier |

| 2nd Infantry Division of the Young Guard | General Barrois | ||

| II Corps of the Young Guard | Marshal Ney | 3rd Infantry Division of the Young Guard | General Decouz |

| 4th Infantry Division of the Young Guard | General Roguet | ||

| Guard Artillery | |||

| XIV Corps | Marshal Gouvion Saint-Cyr | 43rd Infantry Division | General Claparède |

| 44th Infantry Division | General Berthezène | ||

| 45th Infantry Division | General Razout | ||

| 10th light Cavalry Division | General Pajol | ||

| I Corps of Cavalry | General Latour-Maubourg | 1st light Cavalry Division | General Berkheim |

| 3rd light Cavalry Division | General Chastel | ||

| 1st heavy Cavalry Division | General Bordesoulle | ||

| 3rd heavy Cavalry Division | General Doumerc | ||

| Infantry Division | General Teste | ||

| Dresden Garrison | General Durosnel | ||

| II Corps | Marshal Victor | 4th Infantry Division | General Dubreton |

| 5th Infantry Division | General Dufour | ||

| 6th Infantry Division | General Vial | ||

| VI Corps | Marshal Marmont | 20th Infantry Division | General Compans |

| 21th Infantry Division | General Lagrande | ||

| 22th Infantry Division | General Frederichs | ||

| V Corps of Cavalry | General L'Héritier | 9th light Cavalry Division | General Klicki |

| 5th Dragoon Division | General Collaert | ||

| 6th Dragoon Division | General Lamotte |

Allied order of battle

| Army of Bohemia | Schwarzenberg | Austrian Forces | Schwarzenberg | III Corps | Giulay | 2nd Infantry Division | General Weissenwolf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4th Infantry Division | General A. Liechtenstein | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd Reserve Division | General Crenneville | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd Cavalry Division | General Lederer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IV Corps | Klenau | 1st Infantry Division | General Mayer | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd Infantry Division | General Hohenlohe-Bartenstein | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd light Division | General Mesko | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cavalry Division | ? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reserve Corps | Hessen Homburg | 1st light Division | General M.Liechtenstein | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Infantry Division | General Colloredo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd Infantry Division | General Karl Léopold Civalart d'Happoncourt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Reserve Division | General Chasteler | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd Reserve Division | General Bianchi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Cavalry Division | General Nostitz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd Cavalry Division | General Schneller | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian-Prussian Forces | Barclay de Tolly | Battle Corps | Wittgenstein | I Corps (russian) | Prince Gorchakov | 5th Infantry Division | General Mesentzov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| II Corps (prussian) | von Kleist | 9th Brigade | General Klux | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10th Brigade | General Pirch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11th Brigade | General Ziethen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12th Brigade | General Prinz von Preussen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cavalry Reserve | General von Roeder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian Guard Division | General Roth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cavalry Corps (russian) | Pahlen | 1st Hussar Division | General Milesinov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Infantry Reserve | General Miloradovitch | III Grenadier Corps (russian) | Raievski | 1st Grenadier Division | General Choglokov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5th Guards Infantry Corps | Yermolov | 2nd Infantry Division | General Udom I | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cavalry Reserve | Grand Duke Constantine | Cavalry Reserve Corps | Prince Galitzine | 1st Cuirassier Division | General Depreradovich | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd Cuirassier Division | General Kretov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd Cuirassier Division | General Duka | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Guards Light Cavalry Division | General Chevich | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prussian Guard Cavalry Brigade | Colonel von Werder | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.