Date and place

- May 2nd, 1813 near Lützen, eighteen kilometers southwest of Leipzig (now in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, Germany).

Involved forces

- French army (120,000 men) under Emperor Napoleon I.

- Prussian and Russian armies (95,000 men) under Marshal Ludwig Adolf Peter zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Ludwigsburg.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 18,000 dead, injured or prisoners.

- Prussian and Russian army: 10,000 to 20,000 dead, injured or prisoners.

Aerial panorama of the battlefields of Rippach and Lützen

The Battle of Lützen inaugurated the Saxon campaign. It was the first major battle fought by Napoleon after the Russian campaign. Their defeat demonstrated to the Allies that the Emperor and France still had unsuspected resources after the disaster suffered the previous year. The lack of cavalry, however, prevented Napoleon from fully exploiting his success and limited its consequences.

General situation

At the end of 1812, having driven Napoleon and the remnants of the Grande Armée from their homeland, the Russians did not stop at their border, but crossed the Niemen River to invade Poland, before entering Germany. Prussia took advantage of this to shake off the French yoke and switch to the opposing camp (March 16, 1813).

Meanwhile, in the French army, command passed from Napoleon to Joachim Murat and then, after Murat's defection, to Eugène de Beauharnais (January 13, 1813). The latter had to try to contain the advance of the new coalition with the help of the survivors of the previous campaign, the garrisons holding the German fortresses and, a little later, some help from France. Greatly outnumbered, his troops slowly retreated to the left bank of the river Elbe .

Until April, Mikhail Illarionovich Golenishchev-Kutuzov (Михаил Илларионович Голенищев-Кутузов), General-in-Chief of the Allied Army, proceeded with his usual caution. Waiting for additional forces, which he considered indispensable (he had only limited confidence in the Prussian army), considerably slowed down operations. After his death from septicemia on April 28, 1813 - which was concealed from the soldiers so as not to spoil their morale - Russian general Peter Wittgenstein (Пётр Христианович Витгенштейн) took his place.

Strategic objectives

Once the expected reinforcements had arrived and the river Elbe had been reached, the Allies planned to reconcentrate the army. They would then send light troops to outflank the French left, while gathering the bulk of their forces on the opposite side. Leaning on the Bohemian mountains, the latter will act according to circumstances, but always en masse.

The main advantage of these hazy combinations was that they took place close to the borders of Austria, whose forthcoming rallying to the coalition was almost self-evident in the minds of both Russian and Prussian commanders.

Emperor Napoleon I joined the army on April 25. His priority was to drive the Allies from the left bank of the Elbe and force Saxony to honor its commitments. To achieve this, he brought together the forces at his disposal:

- Eugène's Army of the Danube,

- the Army of the Main (composed of new units hastily raised and organized for the most part in the valley of this river, hence its name)

- the Italian Observation Corps, under the command of general Henri-Gatien Bertrand .

All in all, this represented some 220,000 men, compared with the Allies' 120,000 or so.

When the time came, all these units would move to the right bank of the river Saale, then move out of Leipzig to confront the enemy's center of gravity, which could logically be expected to be to the southeast of the city.

If the allies would accept the challenge, their numerical inferiority would lead to defeat. If, on the other hand, they would allow themselves to be drawn to the upper Saale and Frankenwald by the Emperor's demonstrations there, the bulk of the French army would find only small detachments in front of it. Napoleon would then advance rapidly on Dresden , cutting off the communications of the coalition forces and blocking them at the foot of the Bohemian mountains.

Even the first hypothesis, the least unfavorable to the Allies according to Napoleon, could lead to disaster, as the proximity of the Elbe would help.

From April 25 to 30, the Main army continued its advance towards Leipzig via Naumburg and Weissenfels, while the Elbe army concentrated on Merseburg and Bertrand headed for Coburg via Nürnberg. This convergent movement took place in the shelter of the river Saale: its left bank indeed had become inaccessible to the enemy since the 29th, once the towns of Halle and Mersebourg had been occupied and their bridges brought under French control.

The numbers

On the evening of April 30th, the composition, strengths and positions of the various units were as follows:

French side

| Army of the Main | III Corps | Marshal Ney | 45,000 men | Five divisions : Souham, Brenier, Girard, Ricard, Marchand. Other corps had three unless otherwise noted | HQ and four divisions were east of Weissenfels. The Marchand division was in Stoessen |

| IV Corps | General Bertrand | 30,000 men | This corps brought together the Württemberg division (Franquemont) and two divisions of the former Italian Observation Corps (Peyri and Morand). | The Morand HQ and division were in Dormburg except three battalions positioned in Camburg. The Italian Peyri division was in Jena, the Württemberg division occupied Burgau, Kola and Rudostadt | |

| VI Corps | Marshal Marmont | 25,000 men | Four divisions in theory, three in practice: Compans, Bonnet, Friederichs, the fourth not yet formed | The HQ and two divisions were in Naumburg. Friederichs division in Kösen. | |

| XII Corps | Marshal Oudinot | 25,000 men | This corps brought together a Bavarian division (Raglowich) and two divisions from the former Italian Observation Corps (Pacthod, Laurencez). | Stretched between Saalfeld and Coburg. | |

| The Guard | General Dumoustier (Young Guard) | 11,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry | The Old Guard division and cavalry were in Weissenfels, the Young Guard division in Naumburg | ||

| Army of the Elbe | XI Corps | Marshal Macdonald | 22,000 men | Divisions Gérard, Fressinet and Charpentier | One league east of Merseburg |

| V Corps | General Lauriston | 22,000 men | Four divisions: Maisons, Puthod, Lagrange, Rochambeau | Behind Merseburg. A regiment in Halle | |

| Sardinian Division | General Roguet | 3,500 men | In Merseburg with army HQ | ||

| 32nd division | General Durutte | 4,500 men | In Schafstadt | ||

| 4th division | Marshal Victor | 6,000 men | At Bernburg and along the river Saale, from Wettin to Barby, downstream from Halle | ||

| I Cavalry Corps | General Latour-Maubourg | 4,000 cavalry | One league east of Merseburg | ||

| Westphalian Division | General Hammerstein | Assembled at Sandershausen |

However, the XII Corps and the Württemberg division were at least two days' march away. In addition, the strength of the Army of the Elbe was a quarter below Napoleon's expectations, as Prince Eugene had left numerous detachments with Marshal Davout on the lower Elbe. Finally, the Durutte division was intended to guard Merseburg. Napoleon thus had a maneuvering force of just over 150,000 men (135,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, 400 cannon).

On the coalition side

| Wittgenstein's Army | Berg Corps | 7,500 men | Marching towards Zwenckau from Schkeuditz (northwest of Leipzig) |

| Yorck Corps | 7,500 men | Marching towards Zwenckau from Leipzig | |

| Kleist detachment | 6,000 men subtracted from the strength of the previous two | Ensured the guard of Leipzig | |

| Wintzingerode Corps | 5,000 cavalry and 8,500 infantrymen | The cavalry was located not far from Luetzen, the infantry to the west of Zwenckau, between the river Elster and the Flossgraben canal | |

| Blücher Corps | 27,000 men | A little north of Borna | |

| Russian Guard | 18,500 men | Spread between Frohburg and Kohren | |

| Miloradovich Corps | 12,000 men | Slightly south of Penig |

Total strength, including a few unaccounted-for volunteer units, was around 95,000 men, including 65,000 infantry, 22,000 cavalry and 8,000 artillerymen with 530 to 550 cannon.

Tactical considerations

The Allies decided to fight on the left bank of the river Elbe . They considered that the opposite course of action would necessarily lead to a prolonged withdrawal. This would have deleterious consequences for both troop morale and public opinion in Germany and Austria, which had previously been very favorable to the coalition.

Moreover, the Russian and Prussian commanders considered their forces to be of much better quality than those of the French, and were counting in particular on the excellence and numerical superiority of their cavalry. They relied on cavalry to provide accurate and up-to-date information on enemy movements, to conceal their own maneuvers from the enemy, and to protect the retreat in the event of a setback. They were just waiting for an opportunity to attack.

However, they were mistaken about Napoleon's intentions, convinced that the latter, virtually devoid of cavalry, could not contemplate advancing on Leipzig across a plain favorable to the deployment of his opponents' cavalry. They assumed that he would remain in moderately hilly areas and would therefore have to open up on the Zeitz and Altenbourg sides, especially as he had considerable reserves on the upper Saale. As a result, the coalition troops were concentrated between Leipzig (to the north) and Borna (to the south).

For his part, Napoleon sensed the decisive victory he needed to avoid the defection of Austria and the members of the Confederation of the Rhine. To achieve this, he had to quickly capitalize on the favorable situation he had succeeded in placing himself in after the initial operations. For the time being, the opposing troops were relatively dispersed between Dessau in the north and Zwickau in the south, with the bulk of their forces concentrated between Leipzig and Altenburg. This was more or less what he had anticipated.

As a result, he felt that the time for action had come. For if the enemy did not yet seem to have realized the numerical superiority of the French, nor did they seem to have perceived the Emperor's intentions, this could not last. When Wittgenstein would see the four French divisions of the Upper Saale (XII Corps and Württemberg Division) advancing on Naumburg, he inevitably would deduce that the enemy intended to outflank his right and force him into a reverse-front battle.

So, swift action was needed to forestall this realization, and to prevent the coalition troops from retreating behind the Elbe River. Consequently, the Emperor decided to march without delay on Leipzig via Lützen with the forces available, judging that the enemy was probably concentrating his attention on the movements of the French troops in Upper Saale.

Moreover, the presumed mediocrity of the Allied high command stimulated his audacity. Wittgenstein did not have a glowing reputation and, in any case, his hypothetical talents would be restrained by the need to deal with the entourage of the Russian and Prussian sovereigns. Reconciling their different conceptions could only make his direction of operations sluggish and hesitant.

Last moves before the battle

On May 1st, the Army of the Elbe advanced as far as Schladebach, a few kilometers west of Leipzig, while III Corps, reinforced by Guard cavalry, marched on Luetzen from Weissenfels. Two divisions of the VI Corps supported it, while the third held on to Naumburg.

During a battle near the village of Rippach [51.22674, 12.06877], Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessières was killed by a cannonball that pierced his chest.

The French positions were as follows:

| Army of the Main | III Corps | Division Souham | At Kaja, Rahna, Klein-Görschen and Gross-Görschen |

| Division Girard | At Starsiedel | ||

| Division Brenier | Near Lützen | ||

| Division Ricard | Near Lützen | ||

| Division Marchand | At Lützen | ||

| IV Corps | Headquarters | At Stoessen | |

| Division Morand | At Stoessen. Vanguard at Pretzsch | ||

| Division Peyri | At Gross-Gesterwitz | ||

| Württemberger division | At Jena | ||

| VI Corps | Headquarters | Near Rippach | |

| Division Bonnet | On the heights east of Rippach. Two battalions at Mellschütz | ||

| Division Compans | Near Lösau | ||

| Division Friederichs | At Naumburg | ||

| XII Corps | Divisions Raglowitch, Pacthod, Laurencez | Staggered from Kahla to Saalfeld | |

| Guard | Old Guard division | At Weissenfels | |

| Young Guard division | At Weissenfels | ||

| Cavalry of the Guard | At Lützen | ||

| Army of the Elbe | XI Corps | Divisions Gérard, Fressinet and Charpentier | At Quesitz and Markranstaedt |

| V Corps | Four divisions (Maisons, Puthod, Lagrange, Rochambeau) | Behind Punthersdorf. A regiment in Halle | |

| I Cavalry Corps | General Latour-Maubourg | Between Schladebach and Oetzsch | |

| 32nd division | General Durutte | At Merseburg | |

In view of these moves, the coalition forces realized that they had made a mistake regarding the Emperor's plans. But they immediately made a new one by imagining this march as a long processional column, poorly guarded on the Pegau side. Wittgenstein saw in this the possibility of a flanking attack from this direction.

On the evening of May 1, the Allied Corps occupied the following positions, from north to south:

- Kleist occupied Leipzig

- York and Berg surrounded and protected Zwenckau, where headquarters were located

- Wintzingerode was closing in on the French at Stönzsch

- Blücher was arriving at Rotha

- The Russian Guard reached Borna

- Miloradowich was entering Altenburg

Wittgenstein's surprise effect was crucial to the success of his ambush of the French army. His plan was to concentrate his forces near Gorschen by marching at night without the enemy's knowledge, and then to take action very early in the morning, before the situation had had a chance to evolve.

On the night of May 1 to 2, 1813, his generals received their movement orders for the following day:

- Miloradowich had to advance on Zeitz to guard the roads to Naumburg and Jena. This move was justified by the fear that French troops in the vicinity of these two towns would throw themselves on the Allies' rear when they were engaged at Lützen.

- Witzingerode would move a little to the north, to Werben, to protect the crossing of the Elster and Flossgraben rivers by the bulk of the army (with the exception of a 1,500-strong detachment assigned to guard the Zwenckau bridge).

- At 5 a.m., Blücher would cross the Elster in two columns, north to Storkwitz and south to Pegau, as will the Russian guard. Berg would intervene between Bluecher and the Russians at Storkwitz, and Yorck at Pegau. Two hours later, the movement completed, the army would have take up position beyond the Flossgraben; its right leaning against this stream near Werben; its left taking support on the Grünabach, near Söhesten .

During the same night, Napoleon learned that the enemy had moved corps (Berg and Yorck's) originally stationed in Leipzig to Zwenckau. This movement convinced him that the Allied army was concentrating on this new position.

He fervently hoped it was with a view to attacking them on the west bank of the Weisse Elster.

The adventurous nature of the newly-appointed Russian General-in-Chief, Ludwig Adolf Peter zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Ludwigsburg, made it possible to envisage such an initiative, although it was not in his best interests to do so. Indeed, with this river in his rear, he would be putting himself in an even more unfavorable situation than the one the Emperor was trying to lead him into.

Napoleon, however, was not content to wait for this mistake. Standing ready to take advantage of any enemy recklessness, he advanced his left towards the Elster, in order to seize the city of Leipzig. He intended to break out en masse to outflank the Allied right. At the same time, he moved his own right closer to his center, to keep it out of sight. The center, for its part, did not move; at Kaja and Lützen, it served as a pivot for the rest of the army.

Should the hoped-for attack fail to materialize, the left would finish assembling at Leipzig at the end of the day, and part of the center would march on the Weisse Elster. Its mission would be to gain control of the passages at Pegau and Zwenckau, with a view to exploiting them the following day.

Consequently, the Emperor ordered the following movements for the morning of May 2:

- V Corps and 20,000 men of the I Cavalry Corps (20,000 men) will move on Leipzig from 5 a.m.

- III Corps to concentrate at Kaja to guard Pegau and Zwenckau

- XI Corps, and the other half (25,000 men) of the I Cavalry Corps, will assemble at Markranstaedt, to support either the III Corps or the V Corps

- The 3rd division of the VI Corps will join the first two at Rippach between 9 and 10 a.m.

- The Foot Guard will march to Lützen, arriving around 9 a.m

- IV Corps will move to Kaja, arriving there around 3 p.m.

In the event of an enemy attack on Pegau or Zwenckau, III Corps was tasked with containing the attackers and holding them in place while the main army maneuvers. So, in less than three hours, the 45,000 men of the III Corps would be supported by 50,000 others: the XI Corps, the first two divisions of the VI Corps, and the I Cavalry Corps. Three hours later, with the arrival of the rest of the French army, 150,000 combatants would face the 80,000 allies that the coalition would, at worst, be able to assemble on the spot during the day.

Preliminaries

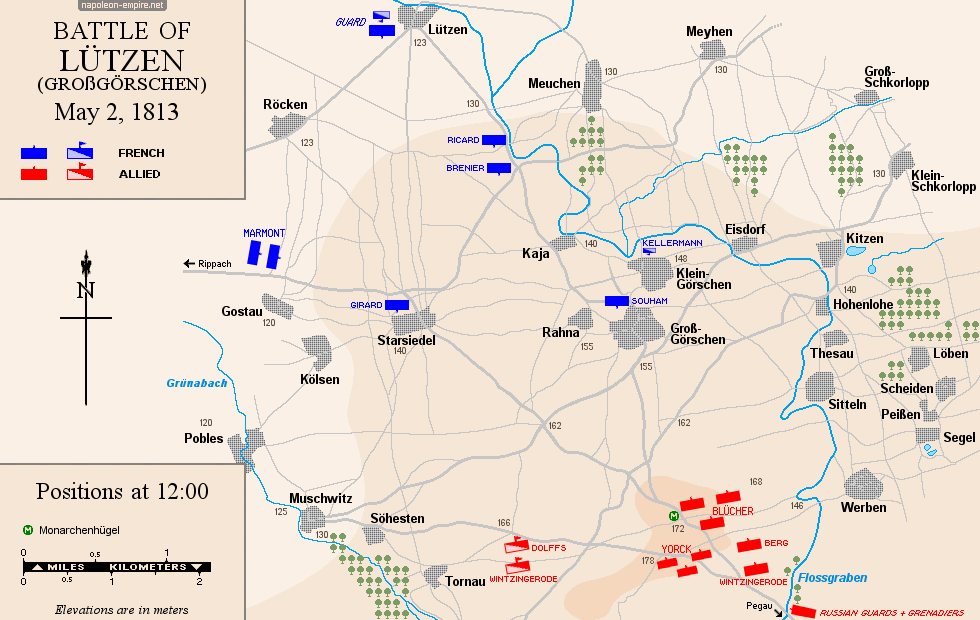

In practice, Wittgenstein's detailed instructions proved to be incomplete, resulting in disruptions and delays to the planned troop movements. Blücher didn't begin crossing the Elster until 7 a.m., and the army didn't finish setting up until 11 a.m., spreading out in three lines two kilometers south of Gross-Görschen, behind a ridge [51.19444, 12.18493].

- The first line was formed by Blücher, whose right was leaning on Werben and whose left was supported by the cavalry reserve opposite Starsiedel

- The second line comprised, from right to left, Berg, Yorck and Wintzingerode

- The Russian Guard served as a reserve. 2,000 of its men guarded the Stönzsch and Werben crossings

The troops were exhausted after marching almost non-stop for twenty-four hours. So Wittgenstein decided to give them an hour's rest before giving the signal to attack.

On the French side, noting that the morning passed without any sign of an Allied offensive, the Emperor gave up hope of seeing the enemy cross the Weiße Elster to attack him.

Consequently, between 8 and 10 a.m., he sent out a flurry of new orders. Although he no longer believed that the enemy would attack, he was still careful to reserve the means to respond in the event of such an attack.

- V Corps to continue its attack on Leipzig

- XI Corps to advance beyond Markranstaedt, while being ready to fork either Leipzig or Zwenckau.

- III Corps to remain at Kaja, where previous orders had sent it (orders which it did not carry out, as its divisions had not left their night positions)

- VI Corps to move to Pegau

- IV Corps to divide its three divisions between Stoessen [51.11539, 11.92521] and Taucha [51.19214, 12.07823]

- The Guard had to remain at Lützen, ready to set off at any moment

These provisions were applied with varying degrees of speed and rigor.

The V Corps moved immediately towards Leipzig. At its head, the Maisons division discovered from the heights of Ruckmarsdorf 3,000 to 4,000 cavalrymen, preceding infantrymen and artillerymen, installed on the plain in front of Lindenau.

They engaged the enemy, drove them back and seized the town's bridges over the Weisse Elster. Around 11 a.m., the other two divisions of the V Corps arrived to occupy the town, while the Maisons division moved forward towards Leipzig.

The XI Corps sent the Gérard division, supported by the I Cavalry Corps, to take up a position south of Schönau in support of the V Corps. The remaining divisions (Freyssinet and Charpentier) spread out between Lausen and Markranstaedt.

The III Corps, on the other hand, still refused to move. Marshal Ney, despite formal orders, had not yet assembled his divisions at Kaja. The Souham division, the only one there, was also holding Rahna and the two Görschen. It was watching Zwenckau from posts established at Hohenlohe, but had taken no action on the Pegau side. Seeing enemy light cavalry occupy the plain from Bösdorf to Hohen-Mölsen was of no concern to anyone.

The VI Corps crossed Starsiedel between 10 and 11 a.m. on its way to Pegau as planned, in order to maintain contact with the III Corps.

Finally, the IV Corps, having failed to receive Napoleon's final orders in time, continued to move its first two divisions towards Taucha in accordance with previous arrangements. During this march, Bertrand noticed the arrival at Zeitz of an enemy Corps (in fact, Miloradovich's vanguard). He informed the Emperor, indicating that he intended to set up his corps near Dippelsdorf, so as to be able to intervene on Taucha and Kaja as well as on Zeitz, according to his instructions.

The battlefield

When they reached the summit of the small hill overlooking Gross-Görschen to the south (the Monarchenhügel) , the Coalitionists discovered the Lützen plain, on part of which the fighting would take place.

The battlefield itself was roughly a quadrilateral. It was bounded:

- East by the Flossgraben (a narrow, shallow irrigation channel with relatively steep, vegetated banks)

- West by the Grünabach (a simple stream that was easy to cross)

- North by a line linking the villages of Kölsen, Starsiedel, Kaja, Klein-Görschen and Eissdorf

- South, by the line joining the villages of Tornau and Werben.

The terrain, gently undulating, was firm enough for armies to move over. Numerous orchards encircled by hedges or earthen embankments were bordering the many hamlets in the area, made up of houses with solid walls but thatched roofs.

The fighting

Arriving at their vantage point, the Allies discovered thousands of French soldiers bivouacked nearby, instead of the small detachments they had expected. Wittgenstein, previously convinced that he could reach Luetzen without resistance, was taken aback. He decided to send an advance guard - an infantry brigade and Bluecher's cavalry reserve - to clear a path for the main army.

At noon, Bluecher received authorization to start fighting. The first cannon shot was fired shortly afterwards.

The infantry brigade advanced directly on Gross-Görschen, while the cavalrymen headed for Rahna on the left. Wintzingerode's cavalry followed, with Starsiedel in their sights.

Gross-Görschen fell without much difficulty. By contrast, the Prussian cavalry pursuing the retreating French had to turn back under fire from the opposing batteries established between Rahna and Klein-Görschen.

The surprise over, General Joseph Souham rallied his division. Since then, firmly entrenched in his positions: right at Rahna, left at Klein-Görschen , he prevented enemy infantry from overtaking Gross-Görschen.

At midday, the Emperor, from Markranstaedt where he was observing the efforts of the V Corps to force the entrance to Leipzig, suddenly perceived the heavy exchange of cannon fire that could be heard behind towards Görschen. After examining the situation through a telescope, Napoleon immediately came up with new combinations.

Far from being surprised, as is sometimes written, he took advantage of the provisions he had made for this eventuality. The pivot he had taken care to maintain at Kaja with the III Corps, in particular, provided him with a point of support. Ney, present at the Emperor's side at the time, left in a hurry, urged to send the Marchand, Brenier de Montmorand and Ricard divisions to support those of Souham and Girard.

Napoleon informed his Corps leaders of the following decisions:

- III Corps must hold its positions at all costs. By stopping and fixing the enemy, it would give the rest of the army time to carry out its maneuvers

- VI Corps would take up a position on the III Corps' right and extend it

- IV Corps would attack the Allied left wing

- XI Corps and I Cavalry Corps would attack the right wing

- V Corps would employ one of its divisions to occupy Leipzig, while the other two would stand by Markranstaedt, ready to advance on Kaja

At this point, around Starsiedel, the Girard division, caught foraging, was in a state of confusion that the arrival of the full VI Corps, in accordance with new orders, would enable it to overcome. Marshal Marmont left a detachment to guard the village and first advanced his divisions in echelons, then, with the growing noise of the fighting at Gross-Görschen, halted them to avoid reckless engagement. The Girard division, once assembled, headed for Rahna, where it linked up with the right of the Souham division.

At 1 p.m., Wittgenstein had to face the facts. He was facing 40,000 French troops camped on a line between Klein-Görschen, Rahna and Starsiedel. The situation therefore differed significantly from the one envisaged, and the surprise was missed. The Allied command nevertheless decided to go to battle, but failed to take advantage of its local numerical superiority to quickly crush its opponents before the rest of the French army came to the rescue.

Instead of delivering the necessary blow, he gradually committed his units as the French strengthened, playing into their hands.

Blücher advanced a second brigade to the east of the first, launched at Gross-Görschen at the start of the engagement. Both then attacked Rahna and Klein-Görschen simultaneously. They captured them despite fierce resistance, including hand-to-hand combat in the nearby orchards. The Prussians immediately attacked Kaja.

Marshal Ney nevertheless had time to reposition his three other divisions: the Marchand division on Eisdorf , to avoid being overrun by the second Prussian brigade, and the Brenier and Ricard divisions on Kaja. He put himself at the head of the Brenier division and took the initiative. The Brenier, Girard and Souham divisions pounced as far as Rahna and Klein-Görschen.

Blücher opposed a few detachments to the Marchand division, but above all brought forward a third brigade and, thanks to this reinforcement, recovered Klein-Görschen and Rahna in his turn. On his left, his reserve cavalry charged the Bonnet and Compans divisions of the VI Corps. These latter held their ground, but Marmont ordered them to retreat to Starsiedel.

To the south, Bertrand, who had finally been able to read Napoleon's morning order around midday, preferred to comply with clearly obsolete instructions rather than react to the cannonade. Yet the cannonade resounded less than six kilometers from his positions. By 1 p.m., the Morand division had moved up between Aupitz and Taucha, while the Peyri division was approaching Aupitz. Bertrand would not engage them in combat until two hours later, when Napoleon had formally ordered him to do so.

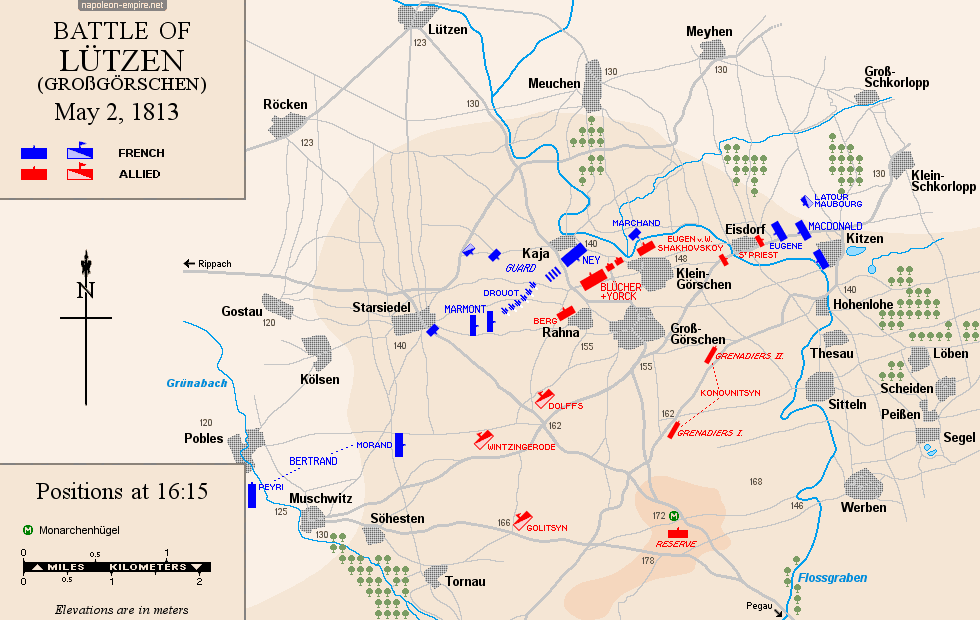

At 2.30 p.m., Napoleon arrived behind Kaja with the Guard. His presence triggers prodigious enthusiasm. As the Prussians continued to advance, in a fight of uncommon intensity, the Emperor sent General Mouton, one of his aides-de-camp, to lead a counter-attack with the Ricard division. Rahna and Klein-Görschen fell back to the French.

On the Prussian left, the battle took on the character of an artillery duel between the Wintzingerode's batteries and those of Marmont's VI Corps. The latter, in view of the mass of cavalry and artillery facing him, demanded reinforcements, which Napoleon refused, replying that the battle was at Kaja.

At around 4 p.m., aware that the French IV and XI Corps were approaching, Wittgenstein decided to finish off the troops in front of him as quickly as possible. He moved the Yorck and Berg Corps forward. The villages of Klein-Görschen and Rahna changed hands once again. Kaja also fell.

By this time, the divisions of III Corps had mixed up and were on the verge of surrendering. The VI Corps could not move from Starsiedel, lest the enemy overrun the III Corps right. The IV and XI Corps were still too far away to intervene effectively. The Guard waited, but the Emperor did not consider the battle ripe enough to engage them.

However, he had to throw himself into the middle of the firefight to rally a few battalions of the III Corps, which were scattering. Shortly afterwards, General Lanusse's Young Guard brigade was sent to attack Kaja, expelling the Coalitionists. The whole III Corps was galvanized and pushed forward.

Shortly after 5 p.m., the XI Corps arrived at Eisdorf, its artillery (60 guns) in the vanguard. At the same time, the Morand division of the IV Corps, which Napoleon had finally ordered into action, broke through on the Pobles side.

With the appearance of these two French corps on its two flanks, the Allied army, fully committed and worn down by the day's fighting, was now facing disaster. Wittgenstein threw the cavalry of the Russian Guard to his left to face the Morand division.

On the other wing, Prince Eugen of Württemberg , commanding the infantry of the Wintzingerode corps, received orders to send half his division towards Eisdorf, beyond the Flossgraben. The half of the division crossed the XI Corps' path, while the rest of the division supported Blücher's attack on Kaja. The assault reached the village, but here too the Allied situation was deteriorating.

The XI Corps had taken control of Eisdorf and Kitzen and was beginning to cross the Flossgraben. The Allied right was now in danger of being caught in the reverse. To the west, the Morand division advanced unhindered by the cavalry of the Russian Guard.

Around 6 p.m., Napoleon judged that the decisive moment had arrived. The III Corps, preceded by the Young Guard division, marched on Rahna and Klein-Görschen, supported by the Bonnet division (VI Corps) on the Rahna side. General Drouot set up the Guard's 60 guns east of Starsiedel. The coalition infantry battalions were machine-gunned from the flank, while the cavalrymen were kept at a distance.

Despite their admirable stubbornness, the Allies had to retreat at every point. By 7 p.m., they were only just holding south of Gross-Görschen. As the day wore on, they withdrew to the ridges between Werben and Tornau, where they found protection from the Russian Guard infantry, who had not fought.

The French, for their part, stopped at Gross-Görschen. Panic in the VI Corps led Marshal Marmont to pull back his divisions and prepare them for a new enemy attack.

Wittgenstein, for whom the battle was lost, ordered a retreat, but Blücher, although wounded, was reluctant. He managed to obtain permission for part of the Prussian cavalry to make a final charge. In the darkness, eleven squadrons set off from Söhesten for the interval between Starsiedel and Rahna.

But these Prussian squadrons lost their way and involuntarily split into two groups. The first fell on Marmont's infantry, the other on the Old Guard units protecting the Emperor's bivouac. Everywhere, they were repulsed with heavy losses.

However, despite its failure, this coup de main was not totally unsuccessful. Fearing further attacks, the French stayed on their feet all night, accumulating the fatigue that would slow their pursuit the following day.

Taking advantage of the darkness, the coalition army withdrew in good order. It crossed the Elster River at the Ostran and Predel fords, upstream from Pegau, protected by Miloradowich's Corps, perfectly intact since it had not taken part in the fighting.

On May 3, the pursuit was entrusted to I Cavalry Corps, V and XI Corps, but the exhausted troops were unable to cover more than fifteen kilometers. What's more, the direction in which the Allies had retreated was still unknown. The first information did not arrive until the night. They indicated that the retreat was proceeding in good order, even if the Russians and Prussians blamed each other for the defeat.

Their retreat first took place via Frohburg and Borna. It then extended to behind the river Elbe , in three columns. The Prussians retreated towards Meisse; the Russians and their convoys both headed for Dresden, but by different routes. Miloradowich remained in the rearguard. On May 4, he retreated to Rochlitz. Kleist, whose Cossacks had entered Leipzig, was ordered to withdraw to Mühlberg. Bülow, covering Berlin, was repositioned at Rosslau.

Results

French losses amounted to some 18,000 men, killed, wounded or taken prisoner (including 12,000 in the III Corps alone).

Although the Allies claimed half that number, it seems that in reality both sides suffered roughly the same number of casualties.

However, when the French army crossed the Elbe a few days later, almost 35,00 men were missing. Deserters and stragglers almost doubled the number of casualties.

Consequences

Neither side achieved its objectives. Although victorious, the French army paid dearly for a success that brought it no significant gains. Defeated, the coalition army was neither destroyed nor even really dented. The dissensions that followed the defeat, although they seemed for a moment likely to lead to a split between the Russians and the Prussians, were soon overcome. To reach a decision, the campaign would have to continue.

Map of the battle of Lützen - Positions at noon

Map of the battle of Lützen - Positions at 16:15

Picture - "Napoleon the First at the Battle of Lützen, May 2nd, 1813". Painted by Louis-François Couché.

This battle is known in Germany as the Battle of Großgörschen.

General Gerhard Johann David von Scharnhorst, one of the main reformers of the Prussian army after the collapse of 1806, was shot in the knee at Lützen. Poorly treated, this initially minor wound led to his death eight weeks later.

As is often the case in Napoleonic wars, the Russian authorities initially took this defeat as a victory. It earned Wittgenstein the Order of St. Andrew and Blücher the Imperial and Military Order of St. George, Martyr and Victorious (albeit 2nd class).

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.