By the end of March 1804, the last of Georges Cadoudal's conspirators were behind bars. Among the information they provided, one piece in particular troubled Bonaparte: the imminent arrival in France of a Bourbon prince. Who it would be remained unknown.

Misleading Clues

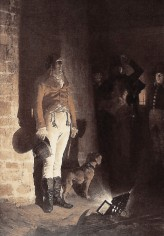

Duke d'Enghien

Enlarge

Louis XVIII was in Poland; the Duke d'Angoulême, his nephew, was with him; the Count d'Artois, the brother of the King, was in England with his youngest son, the Duke de Berry. Suspicion fell on the Duke d'Enghien who was living very close to France in a village 15 kilometres from the boarder called Ettenheim in Baden.

The Consular Police knew he was in contact with enemies of the regime in France (émigrés and royalists). The Police also erroneously believed that Dumouriez had visited him. The Prefect of the Rhine also reported, somewhat incorrectly, large émigré gatherings around Ettenheim.

The correspondence of the English Ambassador, Sir Francis Drake, that was brought to the attention of the First Consul at that time convinced him that a Bourbon would soon be arriving in the Republic.

Ulterior Motives

On March 10, 1804, a cabinet meeting was held that included the three Consuls (Bonaparte, Jean-Jacques Régis de Cambacérès and Charles-François Lebrun) as well as the Minister of External Relations (Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord), the Minister of Police (Joseph Fouché), and the Minister of Justice (Claude-Ambroise Régnier). They decided that the Duke was guilty and resolved to kidnap him in full knowledge that it would result in a tense diplomatic situation.

A delighted Fouché declared that the condemnation of the Duke would allow the First Consul to dispel the myth that he was a French Monk once and for all. Talleyrand was equally satisfied. While forcefully advocating in favour of the final decision, both Ministers were also promoting their own interests. Talleyrand saw it as an opportunity to reinforce his own position at the Ministry of External Relations and Fouché hoped to provoke a definitive break between the royalists and Bonaparte by casting him as a quasi-regicide.

The Kidnapping

Without delay, General Michel Ordener was assigned a detachment of police to carry out the delicate operation. He was in Strasbourg by March 14. He crossed the Rhine during the night of March 14-15. Early in the morning on the 15th, he arrived at the Duke's house and captured him.

The Duke d'Enghien was taken to Strasbourg without being informed of the accusations against him. Ignoring that Bonaparte had decided on March 16 that he would be shot without a hearing, he was at first confident that he would soon be released. However, the following decree was published on March 20: The former aristocrat the Duke d'Enghien is charged with bearing arms against the Republic, with having received and continuing to receive funds from England and with plotting against the internal and external security of the Republic. He will be brought before a military commission of seven members named by the Governor General of Paris, Joachim Murat, that will meet in Vincennes.

The Trial

The First Consul took the step of writing the questions for the accused himself. And he indicated that an affirmative response to the question Have you born arms against your homeland?

must automatically result in the death penalty as the law dictated.

The Duke arrived in Vincennes on March 20 at eleven o'clock in the evening. The military commission met one hour later and was presided over by General Pierre-Augustin Hulin who would pass judgement. (Twenty years later the General would write his Explanation of the Military Commission Formed to Judge the Duke d'Enghien. The Duke believed that he would be able to easily refute the false accusations and insistently asked to meet with Bonaparte, but, according to Napoléon's instructions, these requests were denied.

During his interrogation, he admitted to two crimes that made his sentence inevitable: having born arms against France and having received funds from England. The commission unanimously found him guilty and he was condemned to death. However, the legislation upon which they relied to convict him was inapplicable in this situation. The law was part of the Convention and stipulated that any émigré found on French soil would be subject to the death penalty. But the Duke had be arrested in Baden!

The Execution

Even though the laws stipulated that executions could not be carried out before sunrise, the Duke was summarily shot in the ditch of the château de Vincennes. General Savary gave the order as he had been instructed by Bonaparte to ensure everything went exactly as planned.

Reaction

There were many reactions to these events. Firstly, the violation of the sovereignty of the Duchy of Baden and the kidnapping of the Duke d'Enghien caused little concern.

In contrast, his death polarized public opinion. This led the First Consul to declare, At least, they will see what we are capable of [...] I am the French Revolution, I repeat it and I will defend it.

The Austrian ambassador wrote to his superior, Your Excellence would not know how to conceive of the profound dismay that now reigns here. I doubt whether that caused by the trial of Louis XVI could equal it.

Chateaubriand expressed the anger of the French royalists, at once terrified and indignant, by immediately resigning. But this courageous attitude only underlined the cowardice of the other European chancelleries. The Tsar, who ordered his court to go into morning, was the least spineless. The Pope declared himself to be saddened. The German Emperor kept quiet. The Prussian King had nothing else to say except to assure the First Consul that he hoped "that he had unearthed the extent of the horrible plot against his life." The Duke of Baden chased the émigrés out of his territory. The Duke of Wurtemberg complimented the First Consul. And Charles IV of Spain, the cousin of Condé, approved of the execution.

The Consequences

The break between Bonaparte and the Bourbons was now irremediable and the Count of Provence reaffirmed his claim to the throne. Though he wrote this proclamation on a boat crossing the Baltic because no European sovereign would grant him refuge. He proposed, for the first time, that an amnesty should be granted to those involved in the Revolution to allow them to remain in their positions and ranks in the army and the public service and to guarantee the properties that resulted from the purchase of national goods. This text was addressed to all the sovereigns of Europe and marked an important evolution in the thinking of the future Louis XVIII. He did not receive any response.

Never before had he been so isolated and the royalist cause so despairing. Years of activism had led to the opposite of what had been worked for. As Cadoudal said with sad irony, We wanted to make a king, instead we made an Emperor.

Bonaparte effectively used the events to eliminate the last few obstacles that separated him from the throne. In May 1804, he proclaimed himself Emperor under the name Napoléon I. During the ten years that followed, the counter-revolution was dormant in France.