The eldest son of the Revolution

Even today, some people still see Napoleon as the gravedigger rather than the heir to the Revolution. They criticise him for having re-established a hereditary monarchy, differing in the end from the one that preceded 1792 only in the reigning family.

The supporters of the Ancien Régime were not fooled for long. Their political blindness led them for a moment to dream that Augustin Robespierre's former protégé would become a new George Monck (Olivier Cromwell's former right-hand man, who had helped to re-establish royalty in England after Cromwell's death); their certainty that they represented the only legitimate government led them to imagine, as soon as they were no longer faced with regicides, that the man who had twice victoriously opposed their attempts to seize power - whether violent, as on 13 Vendémiaire, or legal, as on 18 Fructidor - was going to hand it over to them after 18 Brumaire; the response was swift, firm and unambiguous.

Apart from this short and illusory truce, Napoleon Bonaparte was always faced with those against whom the Revolution had been fought. Throughout his career, they were his most determined enemies.

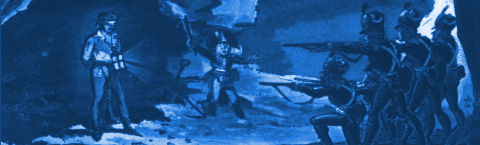

His first successes, at Toulon on 13 Vendémiaire, were achieved against royalist insurrections. Later, as a young head of state, he had to face up to the final fires of the revolts in the West, before becoming the favourite target of the last Chouans chiefs, who were reduced to the role of conspirators and assassins.

Its prestige and power, from 1804 to 1812, then stifled almost any hint of royalist agitation for almost ten years, but setbacks after 1813 unleashed the old hatreds, which were as fiery as ever.

The White Terror then responded to the Republican Terror, as if to frame the flamboyant picture of Napoleonic France with a bloody border...