Date and place

- July 19th to 22nd, 1808 at Bailén or Baylen, in Andalusia (nowadays Province of Jaen, Spain).

Involved forces

- French army (20,000 to 24,000 men, including 2,750 cavalry, 21 cannons) under the command of General Pierre Antoine Dupont de l'Étang.

- Spanish army (29,000 to 35,000 men, including 3,200 cavalry, 28 cannons) commanded by generals Don Francisco Javier Castaños Aragorri Urioste y Olavide and Theodor Reding von Biberegg.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 2,000 to 2,600 dead, 400 wounded, over 17,000 prisoners.

- Spanish army: 240 dead, 740 wounded or the opposite (depending on the sources).

The Battle of Bailén represents the first serious failure suffered by the Napoleonic armies, then considered almost invincible. After his defeat, General Dupont de l'Étang also signed a capitulation, the terms of which earned him, upon his return to France, degradation and condemnation by a commission of inquiry.

Dupont's mission and resources

On May 24, 1808, Pierre Dupont de l'Étang , one of France's most brilliant divisional generals, and one to whom a marshal's baton seemed to be promised, left Toledo with the 12,000 men of the II Gironde Observation Corps.

His mission was to go to Cádiz to rescue Admiral François Étienne de Rosily-Mesros and the remnants of the French fleet defeated at Trafalgar. Since the Spanish uprising at the beginning of May 1808, the latter had been trapped between the English blockade, which prevented them from leaving the port, and the insurrectionary authorities, who were determined to seize the French ships.

The troops entrusted to Dupont were very different from those he had led in previous campaigns. This time, he had at his disposal only young conscripts, second-rate soldiers and reserve units that had been kept out of the fighting. The French command has judged these forces to be sufficient for what, in its view, promised to be a military promenade.

They were divided between three infantry divisions entrusted to generals Gabriel Barbou des Courières , Dominique Honoré Antoine Vedel and Bernard Georges François Frère . They were joined by a cavalry division under General Maurice Ignace Fresia , a battalion of Guards sailors and various artillery and engineering units. Swiss regiments previously in the service of Spain were forcibly conscripted to complete the force.

Beginning of the campaign: Battle of the Alcolea bridge, capture of Cordoba

On June 7, Dupont's troops arrived in Córdoba, having dispersed its defenders at the battle of the Alcolea bridge [37.93671, -4.66174]. They took the city, sacked it for four days and then settled in. It was here that they received the news of Rosily-Mesros' surrender in Cadiz on the 14th. This event invalidated the main purpose of the expedition.

In addition, Dupont learned that the juntas of Sevill and Granada, under the command of general Francisco Javier Castaños Aragorri Urioste y Olavide , were assembling a new army of 40,000 men who were preparing to march on Cordoba. Consequently, on the 16th, the II Corps evacuated the city to move closer to its bases. The march was slow, as the stragglers were attacked by guerrillas whose hatred had been exasperated by the looting for Cordoba, and who did not hesitate to commit the worst atrocities on their victims. The morale of the French soldiers was seriously shaken.

On June 18, Dupont moved to Andújar . The Bailén position offered better defensive guarantees; the offensive was easier from the position chosen by the French general. The orders he had received and, probably, his desire to make his mark with a victory, led him to prefer this solution.

However, finding himself too weak in the midst of a province in full uprising, where small isolated units were bound to be massacred, Dupont repeatedly asked Madrid for reinforcements.

The new authorities in Madrid - Joseph Bonaparte had just been proclaimed king on June 6, and Anne Jean Marie René Savary had replaced the ailing Joachim Murat in some of his duties - agreed to his request for reinforcements. Two additional divisions, those of generals Vedel and Jacques Nicolas Gobert , left to join him.

The additional missions of these reinforcements were to convoy much-needed supplies to the II Corps, and to regain control of the Sierra Morena road, then under insurgent control. It was essential to flush them out, since this route was not only the line of retreat for Dupont's corps, but also, in the eyes of the government, the route by which Spanish forces in Andalusia could threaten Madrid.

Arrival of reinforcements

General Vedel left Toledo on June 19, leading almost 10,000 men and ten cannons. Attacked on the 26th by don Pedro Valdecañas' 2,000 guerrillas in the Despeñaperros pass, which crosses the Sierra Morena, he put them to flight, left a battalion to guard the pass and joined Dupont.

General Gobert left Madrid on July 2 via the Camino Real, with a division drawn from the Ocean Coast army. His troops, however, no longer constituted a reinforcement in the strict sense of the word, as they merely replaced those of General Frère, who had left to take orders from Marshal Bon-Adrien Jannot de Moncey in Valencia.

Gobert also had to re-secure the road, which the insurgents had once again taken control of immediately after Vedel's passage. To ensure communications between Andújar and the capital, he had to leave a large part of his troops along the road. The remainder, about one brigade, joined the II Corps around July 7.

By the time the operations leading up to the Battle of Bailén began, Dupont's forces were extremely dispersed. The Gobert, Vedel and Dupont divisions occupied La Carolina, Bailén and Andújar respectively. There were therefore more than 50 kilometers between the two extremities. What's more, the French soldiers were exhausted by the intense heat and suffering from thirst.

Preliminaries to the battle: the Mengibar battle

On July 15, part of Vedel's battalions clashed with General Theodor Reding von Biberegg 's Spanish division, preventing it from crossing the Guadalquivir River at Mengíbar:

At the end of the engagement, Vedel joined Dupont in Andújar with all his troops, although his commander had only asked for a maximum of one brigade.

The Spaniards took advantage of the situation to cross the river the next day and set up camp in the village. Gobert, who had rushed to the scene with his division, was mortally wounded when he tried unsuccessfully to stop them. General François Bertrand Dufour replaced him and took his soldiers back to Bailén and then to La Carolina.

In the meantime, Vedel, having just arrived in Andújar, was immediately sent back to Bailén, which he discovered empty of Spanish troops. He wrongly deduced (unless he had been naïve enough to believe the false information provided by the population) that the enemy had taken the road to La Carolina behind Dufour and set off in pursuit.

Reding, in fact, had waited for Coupigny's arrival before pushing his advantage. Once the junction was assured, and the position of Bailén opened up to them, the Spaniards made no mistake in taking advantage. The French army was cut in two.

The situation made it imperative to re-establish communications between the two sections as a matter of urgency, and thus to seize Bailén before the Spanish occupied it in force. However, Dupont let a whole day pass without taking any action.

The fighting

On the evening of the 18th, under the cover of darkness, Dupont left Andújar, escaping the surveillance of Castaños' troops, who were stationed nearby in numbers far superior to his own. At dawn the next day, the head of the French column reached the bridge over the Rumblar river [38.08546, -3.83732], five kilometers west of Bailén:

Here, the French encountered a Spanish detachment, which they pushed back to advance to the hamlet of Ventorrillo one kilometer further on. Arriving not far from Bailén, at a place called La Cruz Blanca [38.09234, -3.79166], they were in turn driven back by the opposing vanguard.

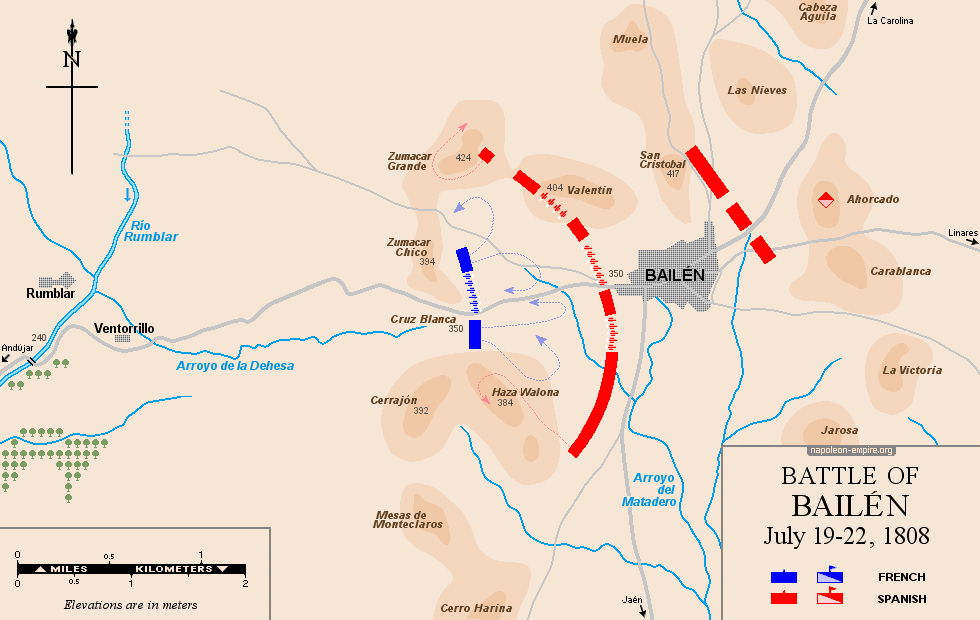

Reding ordered then his troops to deploy on the outskirts of Bailén. They did so, occupying the heights overlooking the roads along which the French would arrive. The wings were set up on the hills of San Valentin, Zumacar Grande, Cerrajón and Haza Walona:

The rearguard, for its part, took up positions on the hills of San Cristobal and El Ahorcado, to the north and northeast of Bailén, to keep an eye on Vedel's possible return.

Francisco Javier Venegas de Saavedra commanded the left flank; Antoine Malet de Coupigny led the right one; Reding, from the center, oversaw the whole operation. The Spanish fielded around 20,000 men. Dupont's column was barely 9,000 strong.

Between four and six o'clock in the morning (depending on the sources), once Dupont had rejoined his vanguard and the bulk of the French column had arrived on the Rumblar, the battle began.

Dupont first brought up Privé's cuirassiers and dragons, supported by Jean Adam Schramm's Swiss infantrymen. The Spanish right, posted on the hill of Haza Walona underwent several assaults and finally gave way, although the terrain, largely made up of olive groves , was unfavorable to the movements of the French cavalry. Curiously, the latter withdrew without exploiting its success.

Schramm's Swiss then took over, but found themselves facing fellow countrymen fighting on the opposite side, and decided to dispense with a fratricidal confrontation. Dupont then launched General Théodore Chabert's brigade. The Spaniards' cannons forced this brigade to turn back, and their cavalry escorted them back without gentleness.

Whereafter Privé's dragoons were sent to the rescue, in order to restore the situation. In the end, all this ebb and flow left everyone in their original positions.

At around 9 a.m., Venegas, supported by a few cavalrymen, attempted to occupy the heights overlooking the French left flank: Zumacar Chico and Zumacar Grande . He was repulsed.

The third French offensive came an hour later. Claude François Dupré's chasseurs and Chabert's infantry tried to break through the center of the Spanish position. But, as in the second attack, the Spanish artillery dislocated the French columns. Moreover, the heat of the day began to weigh heavily on the soldiers' shoulders.

Shortly afterwards, the Spanish went on the offensive in a combined cavalry and infantry operation. The imperial troops retreated. A charge by French cuirassiers and dragoons, led jointly by Ythier Sylvain Pryvé (or Privé) and Dupré, seemed for a moment to be successful. In the absence of sufficient infantry support, its success was short-lived and had no noticeable effect.

The temperature was becoming oppressive. Supplied with water by the local population (a certain Maria Bellido gained a reputation that has lasted for centuries), the Spaniards suffered less than the French, who could not rely on the Rumblar , which had run dry. Reding was even able to cool down his guns, which proved to be ipso facto more effective than those of his opponents.

For Dupont, the situation already appeared almost hopeless: half a day's fighting had failed to break the Spanish lock; there was no sign of Vedel's imminent arrival; Castaños could arrive at any moment.

Consequently, the French general-in-chief concentrated his forces for a last-chance attack.

All the remaining troops available and capable of fighting were launched against the enemy center. To no avail. Spanish artillery, once again, thundered down on the French battalions, breaking their progress. The cavalrymen who had come to the aid of their comrades were swept away in their turn, and General Dupré succumbed in this vain attempt.

Suspension of hostilities

Dupont nevertheless made a supreme effort to break through the enemy lines at the head of the few soldiers still able to fight. He counted just over 2,000, including 400 sailors from the Imperial Guard. The rest were dead or wounded, or had given up and left the battlefield, exhausted by the heat and thirst (temperatures exceeded 40°C).

Despite the presence of the generals on the front line, this final surge was a final failure. Dupont himself suffered a kidney wound, and suddenly succumbed to the same despondency as his troops. Against the advice of General Privé, who tried unsuccessfully to rekindle his leader's ardor by pointing out the existing favorable hypotheses, he requested a suspension of arms.

Reding accepted. The belligerents agreed to each maintain their positions during the negotiations.

At 2 p.m., Castaños arrived in front of the Rumblar and stopped as soon as he was informed of the ceasefire. The Spanish General-in-Chief thus played no more than an extra in a battle in which he was nominally the victor.

Vedel's intervention

Around 4 or 5 p.m., General Vedel finally entered the fray. Although he marched to the sound of cannon fire, it took him no less than 10 hours to cover the 23 kilometers between La Carolina and Bailén, perhaps because he was unable to envisage a French setback.

In any case, his slowness meant he arrived too late to turn the tide. Initially, however, he attacked Coupigny's Spanish division posted northeast of Bailén, on the hills of San Cristobal and El Ahorcado, overlooking the road to Madrid. But Dupont, who had included Vedel's forces in the ceasefire, ordered him in writing to halt the operation, which was on the verge of success. At 6 p.m., the fighting ended, this time definitively.

The next day, Vedel, supported by his generals, his senior officers and the troops, who were particularly irritated by the forced inaction in which they were being held, proposed to his chief that hostilities be resumed.

When Dupont refused, Vedel left that evening for Madrid via the Sierra Morena, not considering himself bound by the suspension of arms, which had been decided in his absence and without his having been defeated.

Dupont then sent him a letter expressly ordering him to join in the surrender. He argued that the Spanish, who believed that Vedel's departure broke the terms of the ceasefire, were threatening to massacre the remaining French units.

Vedel decided to obey, but his troops proved more difficult to convince. The less bellicose side intended to continue on to Madrid, while the other one wanted to retrace its steps to deliver Dupont's army. In the end, however, they all bowed to military discipline and returned, as ordered, to take up positions near Bailén to await the outcome of the negotiations.

Surrender and signing of the Convention of Andujar

Meanwhile, talks began in a post house near Villanueva de la Reina:

Dupont, who was ill, was represented by Chabert. Léonard Charles de Villoutreys, Napoléon's equerry, and Armand Samuel de Marescot, first inspector general of engineering, accompanied him as witnesses.

Dupont hoped that the presence of the latter, a Grand Officer of the Empire and an old acquaintance of Castaños, would soften Castaños up. Nevertheless, the Spanish negotiators proved intractable, especially once they had received a letter from Savary revealing how eagerly awaited Dupont's troops were in Madrid.

Castaños may have played only a minor role in his side's victory, but he was going to make the most of it. He accepted nothing less than total surrender. The French finally resigned themselves to this, signing the Convention of Andújar on July 22, 1808.

Results

The next day, under the terms of the Convention, more than 17,000 Frenchmen, who had nevertheless been accorded the honors of war, paraded before their victors and surrendered their weapons, eagles and flags. 2,500 others (1,500 of them for lack of care) lost their lives on the battlefield. The Spanish, for their part, lost around 1,000 men.

Urged on by England, the Cadiz junta refused to ratify the articles signed at Andújar. Dupont and his generals were quickly repatriated by boat to Marseille and Toulon, while their soldiers, numbering almost 16,000, far from being sent back to France as agreed, were taken to Cadiz.

There, most of them were detained on pontoons (ships stripped of their masts and turned into prisons), which was roughly equivalent to a death sentence, albeit without the leniency of a death sentence.

In February 1829, some of them were deported to the island of Cabrera, others to the Canary Islands. The conditions of detention were draconian, and few of the survivors were released in 1814. The officers, less badly treated, were illegally deported to England in 1810.

Aftermath

The announcement of this defeat, the first suffered by a French imperial army, came as a shock to European opinion. Coming after three years of triumphs won by the Grande Armée across Europe, it revealed to the world that French troops were not invincible, and raised the spirits of all France's enemies.

In Spain, it aroused the enthusiasm of the population and led the insurgents to no longer limit their ambitions to a defensive war. It also encouraged them to organize a unified command of all local resistance movements, which led to the creation of the Central Junta [Junta Suprema Central y Gubernativa del Reino] in Aranjuez.

In the immediate aftermath, King Joseph, installed in his capital Madrid on July 20, left it in a hurry on the 30th, two days before the insurgents entered. The French troops withdrew behind the Ebro River and the first siege of Saragossa was interrupted.

Napoleon himself would soon have to intervene in the peninsula to restore the situation, bringing with him major reinforcements that would one day be lacking in other theaters of operation.

For his part Dupont, the signatory of this catastrophic capitulation, was arrested as soon as he returned to France, tried by a board of inquiry, stripped of his ranks, decorations, titles and endowments, and imprisoned. Marescot, Vedel and Chabert were also condemned.

Map of the battle of Bailén

Picture - « Rendición de Bailén ». Painted in 1863 by José Casado del Alisal.

Dupont's surrender is sometimes attributed to his desire to keep the fruits of the plunder of Cordoba. These were transported in a profusion of carriages accompanying the army. Some Spanish sources, unlikely to be complacent towards the French general, provide an inventory of the convoy. There was nothing to corroborate this suspicion: the eight vans, one hundred and thirty-eight caissons and sixteen carriages accounted for did not appear to be too many to transport the wounded and equipment.

After his victory, Javier Castaños had to wait until 1833 to receive the title of Duke of Bailén.

Rarely has the role of artillery been as decisive as in this battle. The Spanish success was largely due to the superiority of their firepower and the greater accuracy of their cannons.

The eagles lost at Bailén were recovered by Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult in February 1810, during the capture of Seville.

It can be considered that the lack of foresight of the French high command, which seriously underestimated the ardor and determination of the Spaniards at the start of the insurrection, greatly attenuated Dupont's responsibility.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.