Date and place

- July 22nd, 1812 at Arapiles Hills, near Salamanca, Spain.

Involved forces

- French army: 49,000 men under the command of Marshal Marmont, Duke of Raguse, and general Bertrand Clauzel.

- Anglo-Lusitanian-Spanish coalition: 52,000 men under the command of General Arthur Wellesley.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 13,000 men (6,000 killed or wounded, including Marshal and three division generals, 7,000 prisoners), two eagles, six flags, twelve cannons.

- Allied forces: 5,100 killed or wounded (3,100 British, 2,0000 Portuguese, some Spanish).

Aerial panorama of the Salamanca battlefield

The Battle of Salamanca ‒ better known in France as the Battle of Arapiles ‒ was a brutal loss inflicted by General Arthur Wellesley, Marquess of Wellington on the Marshal Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont. It was a decisive blow to the French intervention in Spain.

General situation

After his victories in Portugal the previous year, Arthur Wellesley, Viscount Wellington, resumed the offensive at the beginning of 1812 and moved into Spain. His campaign led him into conflict with Marshal Marmont's army.

The English general-in-chief believed he could beat Marmont's army even without reinforcements, and that this victory would open the way to the capital, Madrid, perhaps causing the French to evacuate half the country.

He also believed that if the French knew of the danger and chose to reinforce Marmont, they would only be able to do so by weakening the Army of the South, commanded by Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult. Soult would then have a hard time preventing the Cadiz junta from regaining control of southern Spain, all the way to the river Tagus.

The Coalition's successes in Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz allowed it to push the French back towards Extremadura; in mid-June, the Anglo-Portuguese captured Salamanca and continued to push forward.

Over the following weeks, Marshal Marmont managed to contain the offensive. The French army tried a counter-attack on the Allied communication lines, which led Wellington to retreat to Portugal on the evening of July 21.

Preliminaries

On the night of July 21-22, 1812, Marmont, Claude François Ferey and Antoine Louis Popon de Maucune met at a council of war to support the idea of a battle, while Maximilien Foy and Bertrand Clauzel were against it. The latter two unsuccessfully tried to convince Marmont that he should wait for back-up and that it would be in the enemy's interest to attack in the current circumstances.

On the morning of the 22nd, Wellington sent his army's baggage back to Ciudad Rodrigo, but he decided to observe the French army's movements before continuing to retreat with the rest of his troops. He planned to withdraw soon, unless circumstances allowed him to attack.

In the meantime, he used the local topography to hide his movements. The French could only see his 7th division from their position, which was on top of a ridge to the west. That was only a small part of the forces available to him.

Wellington, on the other hand, was shielded from his enemies' attention, but could clearly see their positions. He observed masses of troops to the east and south, suggesting that his adversaries were trying to outflank him on the right.

He then tried to seize the two hills named Arapil Chico [40.89667, -5.62744] and Arapil Grande [40.88908, -5.62480]:

But he only succeeded in capturing the first hill .

The French took the second one from the Portuguese, who were already settling there. Marmont then moved his headquarters and an artillery battery to the Arapil Grande.

French troops were now positioned as follows:

- General Foy's division was positioned around the hermitage of Nuestra Señora de la Peña near the village of Calvarrasa de Arriba ;

- General Ferey's division and Pierre François Xavier Boyer 's cavalry brigade were to the northeast of the Arapil Grande, supporting the previous division;

- The divisions of generals Clauzel, Jacques Thomas Sarrut , Maucune and Antoine François Brenier de Montmorand (the latter commanded by general Eloi Charlemagne Taupin ) were grouped to the south of the Arapil Grande, with Jean Pierre François Bonet forming the center on its flanks;

- Jean Guillaume Barthélemy Thomières' division was on the left, occupying another difficult-to-reach brest-shaped-hill called Teston de la Cabaña, where the French had about 20 cannons; the Curto light cavalry brigade was there too.

The morning went by without Wellington finding the opportunity to attack from his position on the Teso de San Miguel . The English general had breakfast while writing his orders to retreat. Meanwhile, the French began their circular movement.

The battle

The beginning of the battle until Marmont's injury

The cloud of dust raised by the coalition's baggage was the turning point of the day. Marmont misinterpreted it as a sign that the allies were withdrawing their infantry, and saw an opportunity to strike their rearguard. However, the chief of staff of the Maucune division told him that British troops were hiding behind the hills. Marmont ignored this warning and planned to attack the rearguard with his left wing, with the rest of the army cutting off the enemy's retreat.

Marmont ordered the Thomières division to spread out to the southwest up to the Miranda peak , near Miranda de Azán , just two kilometers away, with the support of the Curto brigade, the Maucune and Brenier divisions and a regiment from the Bonet division, which would come between the latter and the Brennier division.

This maneuver, designed to cut the road to Ciudad Rodrigo, considerably stretched the French lines on the southern flank. Marmont thought it could be done against a simple rearguard. But in reality it was very dangerous against an enemy that had gathered all its forces under the shelter of the village of Los Arapiles :

Furthermore, it was poorly executed and Thomières had already reached his objective while his supposed supporters were not yet on the line. Wellington was immediately informed of this clumsy move, and saw an opportunity to attack the different French divisions in turn, as the gap between the French left and center had opened up. It was around 4.30 pm.

Wellington immediately took action to make the most of the situation:

- The Henry Campbell 's division and the Charles Alten 's light division remained on the extreme left, facing Foy.

- The Galbraith Lowry Cole and James Leith 's divisions were posted in two lines to his right.

- Next came the Henry Clinton , John Hope and Carlos de España (Roger Bernard Charles d'Espagnac de Ramefort) 's divisions, placed in column behind the village of Los Arapiles.

- Finally, the Edward Pakenham 's division completed the line on the right.

- Pakenham was soon reinforced by two artillery brigades and a Portuguese cavalry brigade commanded by Major-General Benjamin d'Urban , and immediately sent to attack the French extreme left.

The Thomières division was isolated far forward. The division resisted well at first, despite being surprised by the attack and still organized in marching columns. It eventually fell to a bayonet charge, suffered a crushing defeat. Nearly half of the unit's troops - 3,000 men, including the general - were killed.

The survivors fled to join the Maucune division, which was about to share the same fate. They had moved too far from Clauzel for him to come and save them, so they formed up in squares, a suicidal tactic against an infantry force that was falling on them.

The survivors of the two French divisions rushed even further back, pursued by the coalition troops.

At the same time, the dragoons of English general John Gaspard Le Marchant , coming from Las Torres into the village of Arapiles with great force, wiped out a large part of the Brennier division that had carelessly moved forward. Le Marchant did not enjoy his success for long. He died shortly afterwards under enemy fire, from a broken spine.

Around 5 p.m., the Cole and Leith divisions were sent to attack the French center, with support from Clinton and Hope, while the Denis Pack brigade was given the mission to recapture the Arapil Grande:

The Bonet division was initially pushed back (this is when its general was wounded), then they managed to chase the Portuguese down the slopes of the butte, destroying them with the help of the artillery battery at the summit.

During these events, or shortly before (at three o'clock according to the Memoirs of Marmont, at four o'clock according to his report of July 31) - the fact is still unclear - Marmont rushed to his horse to try to restore order in his army, and was seriously wounded in the right side and arm.

The command was then passed to Bonet, who was also quickly killed, as we have just seen. Clauzel was thus left in charge. The French army was deprived of a leader for almost an hour right from the start of a messy battle.

General Clauzel took command

The French left wing was completely overrun when General Clauzel took charge of the battle. Clauzel knew this. He first positioned himself on the Teston de la Cabaña, a plateau to the west of the Arapil Grande, where he was supported by the artillery Marmont set up there in the morning.

Yet, despite the terrible losses inflicted by these guns, the British 4th Division came very close to taking this position. It moved onto the plateau and pushed out half of Clauzel's troops at first. But Clauzel managed to rally his men, and then definitively fought off the attackers.

The new French general-in-chief was now faced with a choice: either to withdraw and reorganize, or to attempt to reverse the battle's fate by relying on the divisions that were still operational - Sarrut's, Bonet's and his own. He preferred the second option.

Counter-offensive attempt

Clauzel decided to attack Wellington's center to cut the allied army in two. He ordered Sarrut to give the three defeated divisions time to reorganize by protecting them with his own. The goal was to create a maneuvering force, supported by cavalry, as soon as possible.

Three regiments of the Bonet division were sent to protect the right flank, supported by General Boyer's dragoons; the Ferey division stayed back to guard the Arapil Grande and support the Clauzel division.

Clauzel advanced onto the battlefield , inflicting heavy losses on the Cole division, whose leader was injured. Clauzel was unable to break through the British center because it was attacked on his left flank by a Portuguese brigade commanded by William Carr Beresford .

This attack broke the French momentum, and they had to halt to fight it off. Clauzel's division held the ground until the British 6th division, led by Wellington himself, moved up to charge Bonet's division. The latter could only retreat in the face of such a ferocious charge, which exposed Clauzel's right flank. Clauzel had no choice but to retreat.

Retreat

By six o'clock in the evening, it was clear that Clauzel's counter-attack had failed. Wellington was advancing everywhere. Sarrut was under attack from three infantry divisions and several cavalry brigades. Clauzel was left with only the Foy and Ferrey divisions. Foy faced the Allied 1st Division and Light Division, while Ferrey guarded a ridge southwest of the Arapil Grande.

Despite Clauzel's orders to hold this position at all costs, Ferey was forced to concede to the Allied 6th division. He set up a new line, which his troops managed to hold for a while, even after their general was killed by a cannonball. They were then forced to retreat again to a wood, where confusion ensued among them. Fortunately for the French, not many English pursued them.

Shortly before he was injured, Clauzel ordered the Foy division, the only one still intact, to cover the retreat of what was left of the French army, at any cost. Despite Wellington's best efforts, he was unable to break through Foy's lines.

Foy gradually retreated to the Tormes River , where the English commander thought a Spanish division would block his path.

But the Spaniards left this position without warning their hierarchy, and the French were able to cross the river by the medieval bridge [40.82564, -5.51765] of Alba de Tormes during the night. According to witnesses, the crossing was so chaotic that a more energetic pursuit would have probably resulted in the total destruction of the army.

The following day, the French army continued along the Peñaranda road towards Valladolid. Its rearguard was heavily attacked by Wellington's German cavalry, led by Major-General Eberhardt Otto George von Bock, and lost several hundred more men. This battle became known as the Battle of Garcia Hernandez [Garcihernández] .

An extremely rare military event happened twice: a cavalry charge broke through a square of infantry, in this case the heavy dragoons of the King's German Legion, an elite unit made up of German subjects of the King of England.

Responsibility for defeat

Although the « Armée de Portugal » (french troups in Portugal since 1809) could not be destroyed, much to Wellington's dismay, it suffered a severe defeat. This was probably due less to the talent of the English general - which was undeniable throughout the campaign - than to his leader's mistakes.

Even though he tried to clear his name in his reports by blaming his subordinates - including Clauzel, to whom the « Armée de Portugal » owes the fact that it did not suffer an even more disastrous fate - it seems that Marshal Marmont bears an overwhelming responsibility for the catastrophe.

His arrogance, his belief in his enemy's inability to take the offensive, led him to commit serious mistakes. He should have never sent several divisions forward without support, simply to inflict light damage on a mere rearguard. When he was injured, the French left flank was so stretched that its destruction seemed inevitable.

The marshal's position on the Arapil Grande must have given him a perfect view of his divisions' movements. He should have intervened before Wellington's attack if Thomières and Maucune had left too much space between them or had not correctly executed their orders.

According to his Memoirs, the marshal was about to do so when an injury deprived him of command. The problem is that the timing of this event is debatable. The Marshal himself had different statements about it: he says it happened at sixteen in his report, and at fifteen in his Memoirs.

In any case, Foy wrote: The Duke of Raguse started the battle... and he did so against Clauzel's advice. The only thing to do was to contain the disaster, and Clauzel did just that. Things wouldn't have gone any better if Marmont had never been wounded.

On that July 22, 1812, it was in the French interest to wait and see. On the day of the battle, King Joseph Bonaparte, whom his brother Napoleon had appointed commander-in-chief of the French armies in Spain on March 16, and who considered it crucial to destroy Wellington's corps, was on his way to Salamanca with around ten thousand reinforcements.

But Marshal Marmont immediately went into battle, even if the news of his approach, sent late, had not reached him in time, or if he did not want to be deprived of the glory of a future success by the presence of the king.

He had often asked for reinforcements in the preceding weeks. He lacked cavalry in particular, and the little he had available was poorly mounted: even the cantiniers' horses had to be brought in. Until then, the military chiefs the king had approched had ignored his requests, preventing him from providing Marmont with the slightest assistance.

And yet, when Joseph finally brought in men and Marie François Auguste de Caffarelli du Falga finally sent 2,000 cavalrymen from the Armée du Nord, Marmont decided to do without them!

Consequences

The Battle of Salamanca was arguably the most serious defeat suffered by the French in Spain at the time. It weakened the foundations of French domination in the kingdom and definitively established the reputation of the English army and its leader, who was said to have defeated an army of 40,000 men in 40 minutes.

Two months later, Madrid, which King Joseph had fled for the last time, fell into the hands of the coalition forces. They soon placed Burgos under siege. As for the French, they abandoned Valladolid to seek shelter behind the river Ebro.

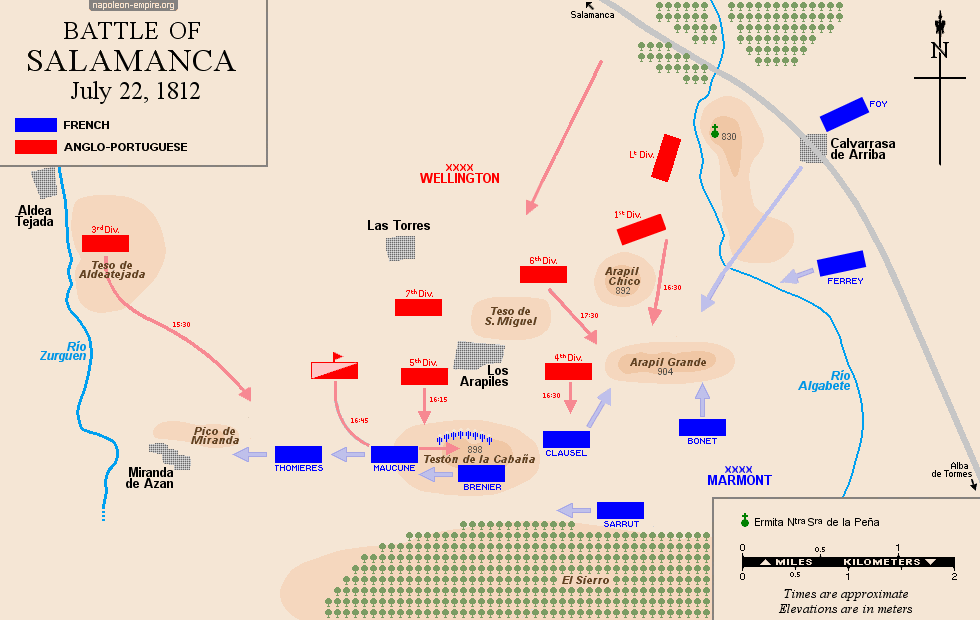

Map of the battle of Salamanca

Picture - "Battle of Salamanca". Author unknown.

Marmont was convinced that Wellington would never launch a large-scale attack, whatever the circumstances. He had two reasons to think so. On the one hand, the British general-in-chief had not yet built his reputation on anything other than his defensive qualities; on the other, the two armies had faced each other for several days at the end of June, with the British, despite their numerical superiority, making no attempt − Wellington had actually been criticized for his inaction.

Marmont's confidence was absolute, and he probably thought he was running no risk by pushing his army's flank against the English. This was a serious mistake.

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.