Date and place

- June 9th, 1800 near Montebello in Lombardy [nowadays Montebello della Battaglia, Province of Pavia, Italy] and Casteggio, an adjoining town.

Involved forces

- French army (5,000 men) under General Jean Lannes.

- Austrian army (12,000 men) under feldmarschall-leutnant Karl Peter Ott Freiherr von Bartokez.

Casualties and losses

- French army : 600 men officially, up to 3000 according to some sources.

- Austrian army : 659 killed, 1 445 wounded, 2 171 prisoners, 2 guns.

Aerial panorama of Montebello battlefield

The Battle of Montebello was the first major battle of the Second Campaign in Italy. The Lombard villages of Casteggio and Montebello, at the junction of the Po plain and the foothills of the Ligurian Apennines, were the setting for the engagement.

The Austrian troops of Field Marshal Peter-Karl Ott confronted the vanguard of the French army, under the command of general Jean Lannes.

General situation

In the second half of May 1800, First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte crossed into Italy with the aim of destroying the Austrian army which was blocking General André Masséna and his troops in Genoa [Genova]. But this reserve army's intervention in the enemy's rear proved too late.

On June 4, after stubborn resistance, the "Child of Victory" (Masséna) agreed to evacuate a city that was literally starving to death - but not before signing an agreement that did not include the term "capitulation".

This setback forced Napoleon Bonaparte to review his plans. He now intended to pre-empt the foreseeable regrouping of Austrian forces, and launched his own troops forward towards Alessandria , with the exception of detachments dedicated to guarding other retreat routes that the Austrians might take.

General Lannes commanded the French vanguard. Setting off from Stradella , he advanced along the road to Voghera and Tortona when, just before Casteggio, he came up against Feldmarschall Ott. The latter, who had rushed from Genoa, was marching on Piacenza to provide the Austrian army with a line of retreat to Vienna [Wien].

This reinforcement, added to the troops of Austrian general Andreas von O'Reilly Ballinlough already occupying Casteggio on his arrival, brought to around 16,000 the total number of troops facing Lannes' 7,000.

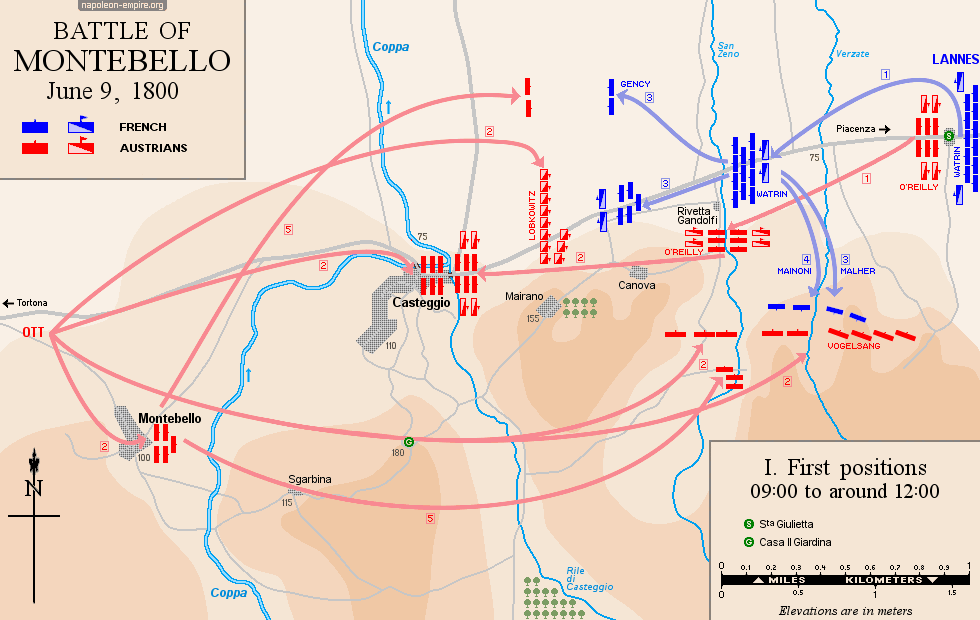

Forces and terrain

The town of Casteggio stands at the confluence of a stream [Rile di Casteggio] flowing from the south and a small tributary of the Po, the Coppa. It has two perpendicular bridges, one on the eastern side of the stream, the other on the Coppa , separated by the market square . The terrain is hilly to the south and flat to the north.

At the start of the battle, the French forces comprised General François Watrin 's division, Joseph Antoine Marie Mainoni 's brigade and a regiment of hussars. General Jacques-Antoine de Chambarlhac de Laubespin 's division, under the command of General Olivier Macoux Rivaud de La Raffinière , was several hours away.

The Austrians, for their part, lined up the divisions of Generals Ludwig von Vogelsang , Joseph von Schellenberg and Andreas von O'Reilly , under the direction of deputy Field Marshal Ott. They also had a large artillery force: 35 guns.

After a patrol reported the presence of French troops to the east, Ott installed six infantry battalions and four cavalry squadrons on this side of Casteggio, under the command of O'Reilly.

The fighting

The first skirmishes took place just before 9 a.m., when the vanguard of the Watrin division, led by General Claude Ursule Gency, came upon the enemy at Santa Giuletta [45.03363, 9.18252], east-northeast of Casteggio.

It withdrew after a brief engagement, which gave the Austrians a false idea of the forces they were up against. As the French were unaware of the arrival of the troops freed by the fall of Genoa, both sides underestimated the strength of their opponent.

At 9 a.m., the French attacked again, and in greater numbers. O'Reilly, forming the enemy vanguard, had to retreat from Santa Giuletta to Rivetta-Gandolfi, to the west-southwest, but managed to repel his attackers.

Two hours later, Watrin sent four battalions to turn the enemy positions to the south, while two others advanced into the plain between the Piacenza road and the Po river. This time, O'Reilly held out for half an hour, before having to withdraw to Casteggio, still heading west-southwest.

Around midday, Ott himself arrived in the town . The position suited him. He deployed the dragoons of the Lobkowitz regiment (Prince Franz Joseph Maximilian von Lobkowitz , Ludwig van Beethoven's protector) on the plain to the northeast, and sent the Vogelsang division and Friedrich Heinrich von Gottesheim's brigade to the heights southeast of Casteggio, where they could dominate the road.

The two branches of the Austrian system formed a roughly right angle, pivoting around the hamlet of Mairano [45.01197, 9.14171].

Thus organized, the Austrians kept the valley under fire with their powerful artillery. They even allowed themselves to keep eleven battalions in reserve, stationed at Montebello , a village three kilometers to the west.

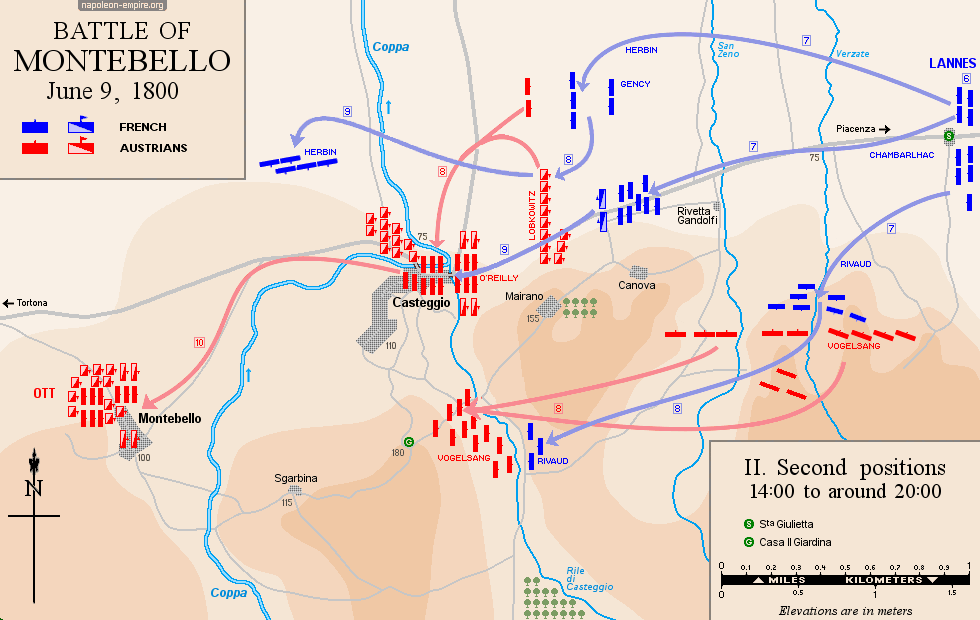

Watrin, who had followed O'Reilly, was immobilized in front of Casteggio by bombardment from the hills. He sent General Jean-Pierre Firmin Malher to attack the Austrian artillery right with four battalions, while Lannes launched a frontal charge towards the same heights. Meanwhile, Gency, with two other battalions, pushed further north towards the enemy's left flank.

Although the frontal assault on the Vogelsang and Gottesheim forces had been repulsed, Malher, after receiving support from Mainoni, reached the crest of the hills and drove the Austrian right to the south-west of Mairano. Faced with the enemy left, French hussars managed to enter Casteggio, but were surrounded and had to retreat with great difficulty.

Seeing his right retreat, Ott sent in half his reserve. Thus reinforced, Vogelsang and Gottesheim reoccupied the heights from which they had just been dislodged. The rest, under the command of Schellenberg, moved against Gency to the north.

In the hours that followed, the village of Casteggio changed hands several times. The French were fighting one against three, and suffering enormously from the Austrian artillery fire. They were on the point of giving in when reinforcements arrived from the Chambarlhac division, commanded by General Rivaud.

Having set off at 11 a.m. from Stradella, 16 kilometers to the east-northeast, it arrived by forced march along the road to Piacenza, which the Mainoni brigade had managed to keep under control. The division was made up of the Rivaud and Jean-Baptiste Herbin-Dessaux brigades, totalling some 6,000 men, bringing the French total to 12,000.

Rivaud immediately attacked the Austrian right wing, forcing it to leave the heights. However, the withdrawal was orderly, and the Austrians once again deployed in line along the stream [Rile di Casteggio] running south from Casteggio towards the village. Their position was supported by the fortified farmhouse "Casa il Giardina", which Rivaud advanced on without delay.

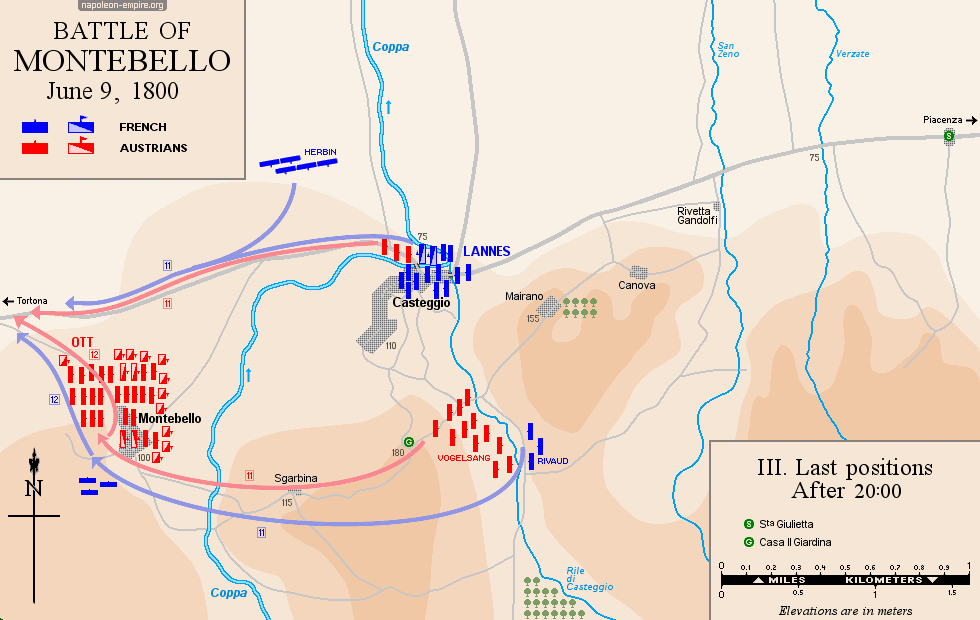

Herbin, for his part, marched head-on towards Casteggio to support Gency. The two bridges were taken, the Austrian center gave way, and the wings were separated, forcing them to retreat. Leaving a rearguard at Casteggio - soon to be captured - Ott set about regrouping his forces around Montebello [44.99670, 9.09942].

The French attacked this new position at around 8 pm. Schellenberg held them off long enough for the rest of the Austrian troops to reach Voghera, then Castelnuovo Scrivia and Pontecurone, before joining General Michael Friedrich Benedikt von Melas in Alessandria .

As night fell, the last defenders of Montebello managed to escape. Lacking cavalry, Lannes was unable to organize an effective pursuit.

Consequences

Despite the heavy losses suffered by Ott, the battle of Montebello did not call into question Michael von Melas' strategy or his position. Gathering his troops before attacking remained his best option.

However, the Austrian general-in-chief's morale was suffering, as evidenced by the absence of any significant initiative for the next five days, until the battle of Marengo.

Map of the battle of Montebello - First positions

Map of the battle of Montebello - Second positions

Map of the battle of Montebello - Last positions

Picture - "The Battle of Montebello, June 8th, 1800. Crossing the Coppo river". Watercolor by Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti.

Jean Lannes was named Duke of Montebello in 1808, in recognition of this feat of arms.

Jean-Roch Coignet (a French soldier and then officer who became a memoirist in his old age) saw fire for the first time at the battle of Montebello. He distinguished himself by seizing a cannon. For this dazzling feat, he was awarded an honorary rifle by Bonaparte's personal order. The First Consul also promised the young soldier a place in his guard at a later date.A new battle - far less deadly - pitted a Franco-Sardinian army against the Austrians at the same location on May 20, 1859. The Austrians were also defeated. The "Bell'Italia" ossuary and the statue entitled "Il Cavalleggero" are dedicated to the combatants of this second battle.

Display the map of the Second campaign in Italy (1800)

Display the map of the Second campaign in Italy (1800)

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.