Origins

Near the end of the eighteenth century, hostility between Great Britain and France came to a head. British products were often boycotted. The ships on which they were transported, even those that were neutral, were declared fair game by a law dated January 18, 1798. The same law also applied to vessels that submitted to English regulations (and this law was applied which put France in a position of undeclared naval war with the United States of America). All means were acceptable to undermine the power of the "vampires of the sea", though an invasion of the British Isles seemed the only sure path to victory.

Finding itself alone after the disintegration of the First Coalition, England began a considerable rearmament campaign. Her army rose to 140,000 men

(though in the past it was more or less inexistent). The navy grew from 40,000 in 1790 to 120,000 in 1799, and voluntary militias were organized to repel a possible invasion. As all of these measures were both financially and politically expensive, a new income tax was imposed, other taxes were similarly raised and the right to habeas corpus remained suspended as it had been since May 23, 1794. They were nonetheless effective.

When Napoleon Bonaparte returned triumphant from Italy, he was given command of a new army by a hesitant Directory (Directoire) and tasked with the invasion of England. He quickly realized the impossibility of his mission. Having understood that he had been assigned an assignment that would destroy his popularity, he publicly announced his opinion after returning from a brief inspection in the west and proposed the conquest of Egypt instead.

Napoleon Bonaparte's Calculations

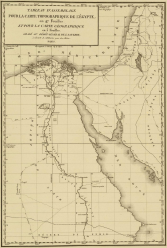

Enlarge

Arguments in favour of this endeavour existed already. In Egypt, France would find an exceedingly well-placed colony. Constructing a canal across the Suez peninsula had been proposed in France since the eighteenth century and would open a new trade route between Europe and the Orient far superior to the British-controlled Cape. Furthermore, Egypt could act as a military base if help was to be supplied to a rebellion against the English in India.

However, the true reasons were less respectable: Napoleon Bonaparte, feeling his hour had not yet come in France, sought to enhance his military reputation with another triumphant enterprise. If I stay, I will soon be sunk,

he confided to Louis Antoine Fauvelet de Bourienne. Already, I no longer have glory. This little Europe has not given me enough. I must go to the Orient. All great victories come from there

(Bourienne, Mémoires). As for the Directory, they were quite happy to put some distance between themselves and this unwieldy national hero.

Preparations and Departure

Bonaparte was given carte blanche to organize his campaign. He surrounded himself with the best the army had to offer and created an expeditionary force of 38,000 men. He was joined by 187 scholars, artists and writers. He also took with him a small group of civil administrators who he thought should form the core of a fledgling colonial government.

Aboard a fleet of 55 warships and 280 transport vessels, the expedition left Toulon on May 19, 1798.

The Conquest

desert

Enlarge

Napoleon Bonaparte reached the strategically important island of Malta in the middle of the Mediterranean on June 10. He conquered the island in three days by defeating the Knights of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. One week later, the fleet continued toward Africa.

Bonaparte miraculously evaded Horatio Nelson who was trying to intercept him and landed in Egypt on July 1. The same day, the French army disembarked at Aboukir and captured Alexandria without difficulty as it was only defended by a weak Turkish garrison.

Three weeks later, the French army faced the Mamelukes. These soldiers were the real masters of the country; they only recognized the Ottoman Sultan's authority in theory. They attacked outside of Cairo, not far from the Pyramids and the Great Sphinx of Giza on July 21, 1799. However, their spirited cavalry charges (10,000 men, the totality of their force) broke against the musket fire from the disciplined squares of the French infantry. The Mamelukes retreated in defeat toward Upper Egypt leaving 2,000 dead on the field of the Battle of the Pyramids. They were pursued by General Louis Charles Antoine Desaix on Napoleon's orders.

This glorious beginning was followed almost immediately by a serious setback. On August 1, Horatio Nelson launched a surprise attack on the French fleet in the Bay of Aboukir and destroyed it. The fate of the enterprise was sealed with the Battle of the Nile. Napoleon Bonaparte had become a prisoner to his conquest.

The Organization

As he put it, he was now "condemned to do great things." He began to modernize and reorganize the country as though the occupation was assured. In some ways, this was his apprenticeship as a sovereign.

On August 22, he created the Institut d'Égypte whose members (Gaspard Monge, Dominique Vivant Denon) set out to create an inventory of the country's resources and incidentally laid the foundations for modern Egyptology. Soon after, newspapers began appearing to communicate the scholars' discoveries. Hospitals, arsenals, mills, and kilns also started to spring up.

The engineers who had been brought along with the expedition began rebuilding the system of canals and introduced new irrigation plans and crop techniques. They also studied the feasibility of a canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. A complete infrastructure was soon in place upon which the founders of modern Egypt relied heavily in the decades to follow.

Napoleon Bonaparte did not forget the importance of good public policies. He had great a respect for Islam, the Qur'an and Mohammed that was more than a simple political expedient to win over local leaders. He severely punished the pillaging conducted by some of his soldiers. He reformed the tax system and adopted a policy of conciliation, though it ran into some difficulties. The results were not always positive, as was attested by the Cairo Revolt on October 21-22, 1798. However, the rigorous repression of this uprising meant the country remained stable until Napoleon's departure from Egypt.

The Syrian Expedition

Bonaparte decided to attack Syria early in 1799. This was mainly to undercut the hostile intentions of the Sultan who had been raising an army ever since his declaration of war against France on September 9, 1798.

The French set out on February 10. The fort of El-Arich was captured on February 20 as was Gaza five days later after a difficult march of over 60 leagues in the desert. On March 7, the fall of Jaffa was followed by the massacre of 4,000 prisoners of war and on March 19 the French laid siege to Saint-Jean d'Acre .

The city resisted, in part thanks to the efforts of a French émigré, Louis-Edmond Antoine Le Picard de Phélippeaux, who had known the young Napoleon Bonaparte in Brienne. Despite his victory at Mount-Tabor over the Sultan's army (April 16, 1799), Bonaparte was unable to break the defenders' resolve. On May 17 the situation became critical and he was forced to lift the siege.

Not only was his army threatened by the plague, but they were also in an exposed position and had been weakened by the losses they had sustained and by the fatigue of battle. More than 600 soldiers fell victim to the plague during the campaign despite the intrepid visits from their Commander in Chief. This made retreat even more difficult since the bodies could not be left behind, especially after the massacre at Jaffa.

Finally, four months after he left, Bonaparte returned to Egypt. This military defeat in Syria could have seriously diminished the trust and moral of the local population, but it quickly erased by Napoleon's political skill. Indeed, he managed to effect a stunning revenge. A Turkish fleet, supported by the English, attacked Alexandria unsuccessfully before landing a new army not far from the city. The French cut them to pieces on July 25, 1799 and named it the Battle of Aboukir as if to erase the memory of the naval disaster from the year before.

The Return

Having finally obtained news of the situation in Europe in a prisoner exchange with the English, Napoleon Bonaparte learnt that a Second Coalition had been formed and that France was experiencing a reversal of fortunes. He immediately understood that the situation in metropolitan France was favourable to his ambitions. His quickly made the decision to return home. This was largely based on the difficult French situation in Egypt: namely, a disastrous strategic position, the loss of the fleet, a greatly weakened army that was no longer capable of a decisive victory (as the failure at Saint-Jean d'Acre had proved), and the impossibility of receiving reinforcements. All of these factors increased the not unsubstantial risk of a capitulation and captivity.

On August 23, 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte boarded the frigate Muiron after handing over command to General Jean-Baptiste Kléber. Some of his collaborators accompanied him. These included Gaspard Monge,Claude-Louis Berthollet, Dominique Vivant Denon, Louis-Alexandre Berthier, Joachim Murat, Jean Lannes, Auguste Viesse de Marmont among others. The fleet was made up of four vessels in total. They arrived in Ajaccio on October 1.

The End of the Campaign

The army did not appreciate what could be seen as a desertion. Kléber entered into talks with the English and even signed a repatriation agreement on January 24, 1800 in Al Arish. But hostilities resumed when the British government refused to accept anything less than a complete capitulation.

On March 20, 1800, 30,000 Turks were defeated at Heliopolis. This was the last French victory in Egypt. This was because Kléber, though a talented general, possessed less political skill than his predecessor. He was hated by the local population because of his brutality and was assassinated on June 14, 1800.

His successor was General Menou (Jacques François de Menou de Boussay) whose attempt to reconcile with the Muslims by converting to Islam only made him look ridiculous in front of his men. In March 1801, he was defeated by an army of English and Turks at Canopus. He capitulated in August.

What was left of the army was repatriated to France aboard English ships.

Assessment

The diplomatic and military results were disastrous. An army made up of the best soldiers of the Republic had vanished little by little in the desert and the Ottoman Empire, traditionally a French ally, had sided with England.

The scientific and artistic results, however, were exceptional. The material collected by the scholars Bonaparte had brought with him was published in 20 volumes between 1809 and 1828 in an monumental work entitled "Description de l'Égypte" ("Description of Egypt"). It became the foundation of modern Egyptology. Within 25 years of the discovery of the Rosetta Stone , the Egyptian hieroglyphs were deciphered after 14 centuries of obscurity.

Egypt itself also benefited from the expedition. The reforms carried out by Bonaparte during his time there and the achievements left behind by the French gave the country a technological advantage over its neighbours and laid the foundations for its relatively rapid development in the decades to come.

Finally, the expedition established France's cultural influence in the region that would continue throughout the 19th century.

Photos credits

Photos by Floriane Grau.Photos by Mr Yves Maillet, whom we thank warmly.