Date and place

- May 30, 1796 at Borghetto, near the village of Valeggio sul Mincio, 25 kilometers southwest of Verona (now in the province of Verona, Italy).

Involved forces

- French army (27,000 to 28,000 men) under the command of General Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Austrian army (6,000 to 18,000 men, depending on the source) under the command of general Johann von Beaulieu.

Casualties and losses

- French army: 500 men (killed or wounded).

- Austrian army: 600 soldiers (killed, wounded or prisoners), 4 cannons.

Aerial panorama of the Borghetto battlefield

The battle took place at Borghetto , on the banks of the Mincio river, below Valeggio castle . It allowed Napoleon Bonaparte to drive the Austrians into Trentino and to blockade the city of Mantua, the strategic lock of Northern Italy.

Austrian dispositions

After the Lodibattle of Lodi on May 10, 1796, General Johann von Beaulieu retreated behind the Mincio , a small river running north-south between Lake Garda [Lago di Garda] and Mantua [Mantova] . He reinforced the city garrison with twenty of his battalions, and then set about defending his position behind the river.

The area to be guarded stretched some thirty kilometers between Peschiera [Peschiera del Garda] to the north and Rivalta to the south. As the French did not have the necessary equipment to build bridges, the Austrians were content to control those that did exist. There were four of these, two of which were impassable for the French, one because it was too close to Mantua (Rivalta bridge), the other because it was inside an Austrian-held square (Peschiera bridge).

This left those of Borghetto [45.35362, 10.72426] and Goito [45.25384, 10.67550]; there was also a ford downstream from Borghetto, which was passable due to the drought.

This position could easily be defended with the men available to Beaulieu if he also had a good line of retreat. But the latter was actually on his right wing and almost in its extension. This was the most direct route to the Tyrol [Tirol], through the Adige valley . Beaulieu could not allow it to be cut, at any price.

This circumstance obliged him to keep the bulk of his army between Vallegio and Peschiera, and prevented him from expecting to put more than 10,000 to 12,000 troops against the French if they attempted to cross.

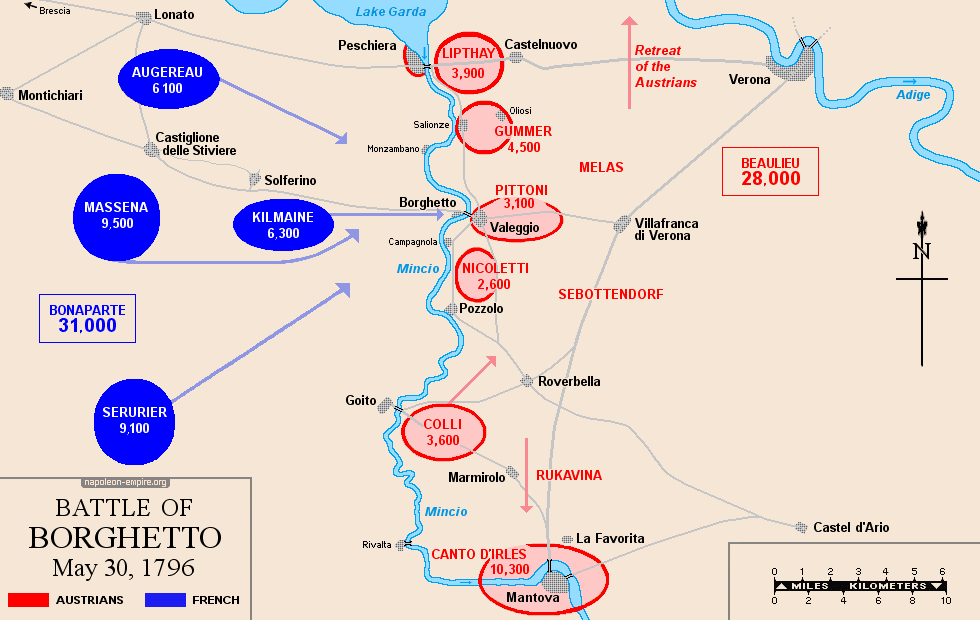

All in all, the Austrian general had some 31,000 men at his disposal. But the troops scattered across northern Italy, beyond Lake Garda and even near the sources of the Adige, were unusable and had to be subtracted. The remainder was arranged as follows:

- the right wing, towards Peschiera, comprised 4,500 men under the command of General Anton Lipthay (or Liptay) of Kisfalud ;

- the center, with 6,000 soldiers, was under the authority of General Karl Philipp Sebottendorf van der Rose. It was based on the village of Vallegio [Valeggio sul Mincio];

- the left wing was based around the village of Goito. General Michelangelo Alessandro Colli-Marchi , who led it, had a few cavalrymen at his disposal, reinforced by 4,500 fighters taken from the Mantua garrison. A total of 5,000 soldiers;

- General Michael von Melas was stationed at Olioso [Oliosi], with 4,500 men forming a sort of general reserve;

- Mantua retained around 9,000 defenders, although a good half of them were responsible for guarding the Chiese and Po rivers, and were therefore outside the walls.

Liptay, along with Colli and Sebottendorf, had placed useless outposts on the right (west) bank of the Mincio, while the general-in-chief had set up his headquarters at San-Giorgio, a little downstream from Borghetto [now probably a district of Valeggio sul Mincio].

The measures taken therefore resulted in a fragmentation of the Austrian forces, which, according to competent commentators, made no sense in the defense of a small river like the Mincio.

French preliminary operations

At the end of May, Napoleon Bonaparte set out for the Mincio from Brescia, with the Masséna, Augereau and Sérurier divisions and the reserve commanded by Charles Edouard Jennings de Kilmaine .

On May 29, 1796, Kilmaine was at Castiglione [Castiglione delle Stiviere] , Charles Augereau at Desenzano , André Masséna at Montechiaro [Montichiari] and Jean Mathieu Philibert Sérurier at Monza. Bonaparte attempted a small diversion towards Salò, on the western shore of Lake Garda, to create the impression of a movement towards Riva and the Tyrol. But the Austrians did not fall for the trap.

At 2 a.m. on the 30th, the French columns set off. Kilmaine, Sérurier and Masséna marched on Borghetto, where they had to force their way through:

Augereau, for his part, advanced on Monzembano [Monzambano] and Peschiera, directly threatening the Austrian line of retreat.

Beaulieu remained at San Giorgio, but was seriously ill, which may have had an impact on the conduct of operations. The Austrians organized themselves to defend the entire course of the Mincio, mobilizing up to the Melas reserve. This decision further dispersed their forces, forcing them to divide the troops along the river into companies and even platoons. The artillery also spread its guns, one by one, along the line of defense. As for the Borghetto and Goito bridges, although mines were prepared, they could not be blown up, as there were still on the right bank (the west one) outposts to be repatriated.

The French attack and the Austrian retreat

As a result of the Austrian dispositions, when the French arrived at the Borghetto bridge, they found only an artillery piece and a battalion facing them, minus one of its companies that had been sent to collect the outposts on the other bank.

At around 7 a.m., General Kilmaine toppled them all. As they rushed back to Borghetto, the Austrians barely had time to throw the bridge planks into the water to prevent the French from following them.

A few Austrian cavalrymen who had remained on the right bank tried to cross the nearby ford, which drew the attention of their enemies. A group of French grenadiers crossed in turn, before quickly taming the feeble resistance of the two Austrian companies and the cannon guarding the passage. Borghetto was immediately evacuated by the Austrians, and the French soon re-established the bridge.

The Austrians withdrew to Valeggio. There, they were joined by the French vanguard, but managed to break free thanks to some fine cavalry charges.

At first, the pursuit was not very brisk, either due to a lack of troops and the need to re-establish the bridge, or to avoid pushing the Austrians too quickly upstream, to give Augereau time to get ahead of them on the road to Castelnovo [Castelnuovo del Garda] .

Mélas, however, by order of Beaulieu, began his retreat in this direction at an early stage, and gave orders to Prince Friedrich Franz Xavier von Hohenzollern-Hechingen, Count of Sigmaringen and Währingen , commanding at Borghetto, to join him. He passed before Augereau arrived.

On the right, General Liptay, who had been ordered to retreat in the morning, was still preparing to do so when he was attacked by Augereau in the afternoon. He succeeded in repelling the assailant and also managed to retreat to Castelnovo, where he entered at dusk, together with Count Hohenzollern. Together, they continued on behind Melas, crossing the Adige at Bussolengo and stopping only at Dolcè, 17 kilometers further north.

Bonaparte first followed his vanguard in the direction of Castelnovo. But when he saw no Austrians anywhere, he turned back to rejoin the Masséna division. The latter was holding out at San-Giorgio, which Beaulieu had just left after nearly falling to the French.

The same misadventure awaited the French general-in-chief: while at his Valeggio headquarters, the Palazzo Guarienti [at no. 27 of today's Via Antonio Murari] , Bonaparte tried to get rid of a headache by taking a footbath, he was surprised by an Austrian squadron on a reconnaissance mission led by General Sebottendorf. Like the rest of the Austrian left wing, the latter had not heard from Bonaparte, and now that the fire had ceased, came to collect.

The few soldiers surrounding Bonaparte barely had time to push back the building's porte cochère, while their glorious leader escaped through the back gate (unless it was through a window), leaving one of his boots to the attackers.

After attempting an attack on Valeggio to help Beaulieu, Sebottendorf, realizing the futility of this effort, retreated to Villafranca and then Bussolengo, where his infantry crossed the Adige , leaving his cavalry to head for Castelnovo.

Colli, informed of the situation even later than Sebottendorf, also attempted an attack on Valeggio, before sending his infantry back to Mantua. For his part, he withdrew with his cavalry to Villafranca and then Castelnovo. He reached Castelnovo at night, where he met up with Liptay and Hohenzollern.

Results

On the following June 3, Bonaparte ordered Masséna to advance on Verona. From there, Masséna pursued Beaulieu up the Adige valley to Rivoli Veronese , forcing him to retreat to Caliano, between Trento and Roveretto, where the Austrian general once again scattered his forces into a multitude of posts. Bonaparte, for his part, blocked the town of Mantua with the Augereau and Sérurier divisions.

From the point of view of military operations, Italy's fate was temporarily sealed.

Map of the battle of Borghetto

Picture - "The Battle of Borghetto". Engraving.

Napoleon Bonaparte's risk of being caught that day prompted him to set up a special unit for his personal protection. Placed under the command of Jean-Baptiste Bessières, this Compagnie des Guides foreshadowed the Garde des Consuls and later the Garde Impériale.

Beaulieu's illness probably had no effect on the outcome of the battle, as its conduct was perfectly in keeping with the spirit of the Austrian general-in-chief, even if the Prussian military theorist Carl Philipp Gottlieb von Clausewitz considered it to contravene the abc of the art of war.

Napoleon Bonaparte's indisposition, on the other hand, probably prevented him from making the most of the break in the Austrian line. Indeed, his lack of zeal in pushing his advantages appears to be the very opposite of his conceptions.

Display the Map of the First campaign in Italy (1796-97)

Display the Map of the First campaign in Italy (1796-97)

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.