Date and place

- April 12, 1796 at Montenotte Superiore, Liguria (now the commune of Cairo-Montenotte, province of Savona, Italy); April 13 at Millesimo and Cosseria; April 14 and 15 at Dego.

Involved forces

- French army (20,000 men) commanded by General Napoleon Bonaparte.

- Armies of Austria and the Kingdom of Sardinia (around 25,000 men) under the command of general-in-chief Johann von Beaulieu and generals Eugène Guillaume de Mercy d'Argenteau and Giovanni Provera.

Casualties and losses

- French army: around 5,000 dead, wounded or missing.

- Austrian and Kingdom of Sardinian armies: around 10,000 dead, wounded, missing or prisoners, 40 cannons.

Aerial panoramas of Montenotte, Millesimo, Cosseria and Dego battlefields

The Battle of Montenotte was General Napoleon Bonaparte's first victory of the Italian campaign. It took place in the rugged, wooded region of northern Liguria.

Preliminaries

On March 27, 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte arrived in Nice to take command of the Italian army. After devoting a few days to the necessary administrative measures, he left the city with his headquarters, by the seaside road and under fire from the English fleet, for Savona. He arrived there on April 9, determined to attack immediately.

With three divisions, he wanted to cross the mountains at the junction between the Alps and the Apennines, where the peaks are lower. With the 25,000 men at his disposal, he would fall on the Austrian center, knocking it down and thus separating the two wings of the enemy. At the same time, General Jean Mathieu Philibert Sérurier was going to fix their reserves by descending the Tanaro valley via Garessio and Ceva. What would happen next would depend on circumstances.

Opposite, Johann von Beaulieu was also determined to go on the attack, but his plan was only to achieve partial successes, in line with the habits of the Austrian general staff. He wanted to cut off all communication between the French and Genoa [Genova], while linking up with the English admiral John Jervis , whose fleet was maneuvering along the coast. The modesty of his ambitions led him to commit himself without waiting to gather his full forces.

On April 10, Beaulieu dislodged General Jean-Baptiste Cervoni from Voltri. On the 11th, he tried to do the same on the heights surrounding Montenotte, but the troops he sent there, commanded by Count Eugène Guillaume de Mercy d'Argenteau , came up against the French troops of Colonel Antoine-Guillaume Rampon, who held the ridge of Monte-Legino [or Monte-Negino] [44.36574, 8.42466] , a strategic observation point , whose summit (altitude 705 meters) had been converted into a redoubt, which was fiercely defended by Rampon and his men [this heroic resistance was illustrated by René Théodore Berthon in 1812 ].

Bonaparte reacted to these attacks by immediately going on the offensive himself with the Amédée Emmanuel François Laharpe, André Masséna and Charles Augereau divisions. The operations that unfolded over the next four days are generally referred to as the Battle of Montenotte, grouping together the battles that took place there and then at Millesimo, Cosseria and Dego.

Battle of Montenotte

During the night of April 11 to 12, 1796, Napoleon brought the Laharpe division up from Madonna di Savona to the redoubt victoriously defended the previous day by Rampon, in order to attack Argenteau from the front.

The Masséna division, soon accompanied by Bonaparte himself, left the vicinity of Vado Ligure to overrun the Austrian right flank via the Cadibona pass and Altare. Bonaparte set up camp near the latter village, on the heights of Casa Bianca, to follow the progress of operations through a telescope.

The Augereau division, which had left Finale earlier, was already on the San Giacomo pass on the 11th. It headed towards Cairo Montenotte , a little further west, with the intention of turning right to join up with Masséna.

While Laharpe valiantly resisted Argenteau head-on, Masséna, aided by the fog, climbed up through the Corvo ravine and the bric de Castellazzo [bric del Tesoro today, bric Catlass in the local dialect, and sometimes noted bric Menau] , north-north-east of Montenotte Superiore . Arriving at Ferriera, he overpowered the battalion guarding the Austrian flank and broke through Montenotte Inferiore to Argenteau's right and rear.

Argenteau reacted by leaving only two battalions in front of Laharpe in an attempt to clear his line of retreat. But the attackers were too numerous, and he was too slow to act. All that remained was for the Austrians to flee in disorder through the Erro valley towards Pontinvrea, where barely 700 of them had regrouped.

Argenteau then withdrew to Pareto, on the road to Acqui [Acqui Terme], between Sassello and Dego, where eleven and just over two battalions respectively were stationed.

Although Augereau did not have the opportunity to take part in the fighting, the French, thanks to the speed of their movements, managed to regroup 14 or 15,000 combatants against 4,000 enemy.

The Austrians claimed 300 dead or wounded and 400 missing. But they also acknowledge the destruction of two complete battalions, and we have seen that, of three others, barely 700 soldiers managed to retreat to Pontinvrea. The actual loss must therefore probably be estimated at 2 or 3,000 men, taking into account those who were later able to rejoin the ranks.

Following this calamitous engagement for his camp, General Beaulieu moved to Acqui, where his forces were assembled.

French losses were far less considerable: a few hundred dead, wounded or missing at most.

Laharpe's orders were to pursue the enemy as far as Sassello, and then to return to Dego through the Bormida valley to support Masséna's attack there the following day. Bonaparte, for his part, with the Augereau division and several fractions of Masséna's, set off for Carcare . He stopped there, but pushed some of his men to the gates of Millesimo.

The battle of Millesimo and Cosseria

Austro-Sardinian troops under the command of general Giovanni Provera were stationed in Millesimo . His task was to provide a link between General Michelangelo Alessandro Colli-Marchi's Sardinians to the northwest and Beaulieu's Austrians to the east. To protect the road through Piedmont [Piemonte], Provera occupied Millesimo with part of his forces, the bulk of which remained at Saliceto , ten kilometers to the north-northeast, and even advanced as far as Cosseria, two kilometers to the east, where he garrisoned the mamelon with troops.

Fighting on April 13, 1796

On April 13th, the Pierre Banel brigade of Augereau division dislodged the enemy from the Millesimo Gorge, and at dawn captured the village and its bridge , cutting off communications with Provera's detachment.

Seeing Bonaparte advancing towards him, Provera, attacked on all sides, retreated to the castle of Cosseria [44.36300, 8.22657]. He was joined there by Colonel Marquis Filippo del Carretto di Camerana, arriving from Montezemolo to the west, having fought his way through Millesimo.

Although the building had been in ruins since the sixteenth century, its dominant position , on a rocky spur between the two Bormida (Bormida di Millesimo to the west and Bormida di Pàllare to the east), made it so difficult to storm that Bonaparte hesitated to give the order. However, when Provera refused to surrender, unless he could leave with arms and baggage to join the rest of the Austro-Sardinian forces, he did so.

Augereau's successive attempts to seize the castle, interspersed with artillery fire, proved to be as difficult as expected and, what's more, unsuccessful. The last, at around 3 p.m., cost the lives of two general officers: Adjutant General Quesnel and Brigadier General Pierre Banel; a third, Barthélemy Catherine Joubert , was wounded.

On the strength of these results, and despite the death of the Marquis de Carretto, Provera refused all offers of surrender made to him during the day. By nightfall, the town was still holding out. The Augereau division remained on the alert until the following morning to prevent the besieged from fleeing under cover of darkness.

While the fighting was going on in Cosseria, Bonaparte, who had left the castle's outskirts to the sound of cannon fire towards Dego, repulsed the few troops sent by Colli to his subordinate's aid around Cengio .

The day enabled the French general-in-chief to drive a wedge into the heart of Beaulieu's position. It was to be exploited over the following days. However, some of Bonaparte's planned operations were delayed.

Masséna, having received confirmation of the order to attack Dego during the night of the 12th/13th, did not feel in a position to obey. Feeling too weak to fight alone in the morning with a division that had been cut back by a brigade held back by his superior, he waited for Laharpe at the appointed rendezvous until noon, and only then set off on the march. As a result, he was only able to carry out a simple reconnaissance, leaving his soldiers stationed at La Rochetta [Rocchetta Cairo] , two kilometers south of his objective.

Epilogue

On the 14th, Colli again failed to rescue Provera. The latter, trapped in the castle of Cosseria without water or provisions after having thrown himself in unexpectedly the day before, was forced to surrender.

The fighting at Millesimo and Cosseria cost the Austro-Sardinians a total of 2,000 to 3,000 men, out of the 3,000 to 4,000 who took part. The French, for their part, lost 1,000 to 1,500 of their 8,000 to 10,000 soldiers. Once again, the suddenness of Bonaparte's movements meant that his troops were outnumbered at the scene of the fighting, despite the fact that the enemy's army was much larger than his own.

Battle of Dego

The Dego site comprised several mamelons. The highest (480 meters), Magliani [44.45415, 8.32376], to the northeast, was crowned by a redoubt. The others (including Cua , the site of Dego castle , halfway between the village and Magliani) were covered with entrenchments.

The French had to seize the position if they were to complete the separation of the Austrian and Austro-Sardinian armies and build on their previous successes. Bonaparte was eager to secure possession of the position as quickly as possible.

After his defeat at Montenotte, Argenteau withdrew to Pareto, 17 kilometers to the north. There, he found a message from General Mathias Rukavina von Boynograd , urging him to rescue the seriously exposed fortress of Dego. Argenteau passed on the request to the General-in-Chief, Jean-Pierre de Beaulieu, while at the same time stating in the same letter that he was far too badly off to provide effective assistance.

Beaulieu nevertheless expressly instructed him to hold Dego for a few more days, thus covering the road to Acqui. The order was accompanied by the dispatch of three battalions from Spigno [Spigno Monferrato]. Beaulieu also ordered General Colli, who was on the Ceva side, to challenge the French left flank.

Obeying his superiors, Argenteau dispatched Josef Philipp Vukassovich (Josip Filip Vukasović) and five battalions to Dego's aid on the night of the 13th/14th. Their orders were to rush from Sassello via Pontinvrea (14 kilometers east of Dego) to attack the enemy's right flank.

April 14th

On April 14th, Bonaparte himself led the assault on Dego, at the head of the Masséna and Laharpe divisions. The town's entrenchments were defended by four battalions (then seven when Spigno's appeared) and eighteen artillery pieces. The French fought enthusiastically, galvanized by the news of Provera's capture.

They went into battle in five columns. Generals Jean-Jacques Causse , Jean-Baptiste Cervoni and Adjutant General Pierre François Joseph (or Xavier) Boyer commanded those of the Laharpe division. General Jean Jacques Bernardin Colaud de La Salcette and Adjutant General Jean Charles Monnier led those of the Masséna division. The latter accompanied Monnier.

The movements of all these units were perfectly coordinated and reached their objectives simultaneously. Causse and Cervoni took the redoubt, while Masséna turned the right.

The false news of Masséna's retreat the previous day kept Argenteau immobile until around two o'clock in the afternoon. Only then, hearing the cannonade, did he march on the town at the head of the two battalions available at Pareto and Malvicinno. Those stationed at Mioglia (19 kilometers to the northeast, via Pontinvrea) were ordered to follow suit.

Time was running out. The troops sent in during the night from Spigno probably intervened too late to restore the situation (the exact time of their arrival is not known). As for Argenteau himself, he arrived at the battle site only to see the village fall to the French. Threatened by Boyer's column and the skirmishers preceding Masséna's, he immediately retreated. Mioglia's battalions did not appear until even later.

All these Austrians retreated during the night towards Acqui via Spigno, trailed by several hundred French.

The Dego garrison was all but wiped out. The Austrian account of the battle itself states that, of the seven battalions engaged in the fight, little or nothing could be saved, not even their eighteen cannons (Napoleon, in his memoirs, will count some thirty).

April 15th

At dawn on the 15th, Vukassovich finally arrived on the outskirts of Dego . As a result of a clumsy drafting error in the orders he had received, he had not set out until the day of the 14th, when the cannon had begun to thunder in the village.

He knew even before his arrival, having learned of it during his march, that he was intervening at the wrong time and that the French had already taken over the square. However, despite having learned from prisoners taken along the way that no less than 20,000 enemy soldiers were stationed there, the Austrian general decided to attack.

In fact, immediately after taking the village, Bonaparte sent the Laharpe division and the Claude Victor Perrin brigade towards Ceva, to reinforce Augereau, who had been advancing on General Colli since he had finished with Provera. Believing the Austrians to be out of the fight for the time being, the French general-in-chief intended to consolidate his left. As a result, only the Masséna division remained in Dego on the morning of the 15th, a maximum of 6,000 men.

Vukassovich's chosen route took him north of Dego , close to the road from Spigno, where the right of the French vanguard was positioned. Overwhelmed by drunkenness, fatigue and sleep, the French vanguard was unable to resist such an unexpected attack, and disbanded. Neither the soldiers nor their leaders had anticipated the attack, and all feared they were up against the entire opposing army.

Taking advantage of the surprise, the Austrians reached the entrenchments protecting the village and seized them, recovering the cannons taken from their comrades the previous day.

Masséna (hastily leaving the bed of a complaisant peasant woman, according to legend) managed to rally some of his fleeing soldiers, but was unable to dislodge Vukassovich from his conquest. Bonaparte, who also interpreted this offensive as Beaulieu's return in force with all his troops, recalled Laharpe and Victor and hurried back to Masséna.

As soon as he arrived, at around 1 p.m., the French general-in-chief ordered a new attack, organized in much the same way as the previous day. His soldiers once again had to climb the Magliani slopes under heavy fire. General Causse lost his life.

The Austrians defended themselves stubbornly and bravely. For a moment, they even managed to rout one of the opposing columns and left the redoubt in pursuit. The Victor brigade soon re-established the situation at this point.

Unfortunately for Vukassovich, there was not a single Austro-Sardinian battalion within a radius of twenty-five kilometers to respond to his requests for help. The lack of support, combined with the risk of encirclement posed by the movements of the French columns, finally forced him to withdraw through Spigno towards Acqui. The Austrians also lost half their forces in the difficult retreat.

Results and aftermath

The total loss suffered by Beaulieu during these four days of fighting cannot be estimated at less than 10,000 men and perhaps forty cannons.

This result was achieved mainly by the Masséna and Laharpe divisions, the Victor brigade and a small amount of cavalry, for a total of just over 20,000 soldiers and less than thirty cannons. It was therefore the fruit of combinations conceived by the French general-in-chief, and brilliantly executed by his subordinates and their troops.

This strategy of successive engagements against fractions of the opposing army was a complete success. A pitched battle against the Austro-Sardinians, with their 30,000 men and 140 artillery pieces, could only have led to the opposite conclusion.

Following these successes, Bonaparte, who had now cut the enemy army in two, made a change of front to attack the Sardinians at Colli.

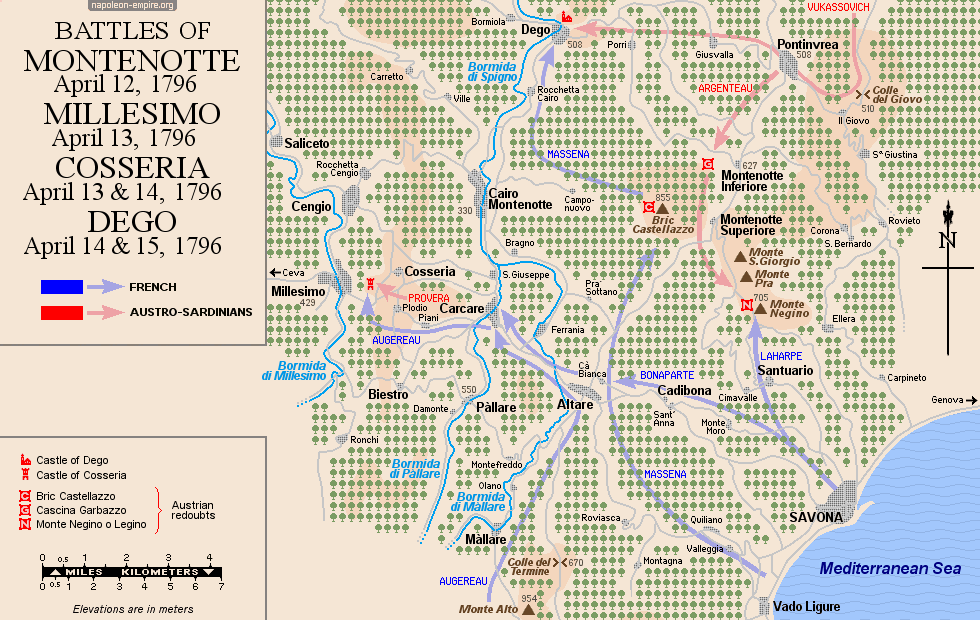

Map of the battles of Montenotte, Millesimo, Cosseria and Dego

During the first operations of the Italian Campaign, Napoleon Bonaparte's headquarters were successively:

- Albenga (Palazzo Rolandi Ricci) , from April 5;

- in Carcare (Casa Ferrero) during the Millesimo, Dego and Cosseria operations;

- at Millesimo on the evening of the battle of April 13.

Map of the battle of Montenotte

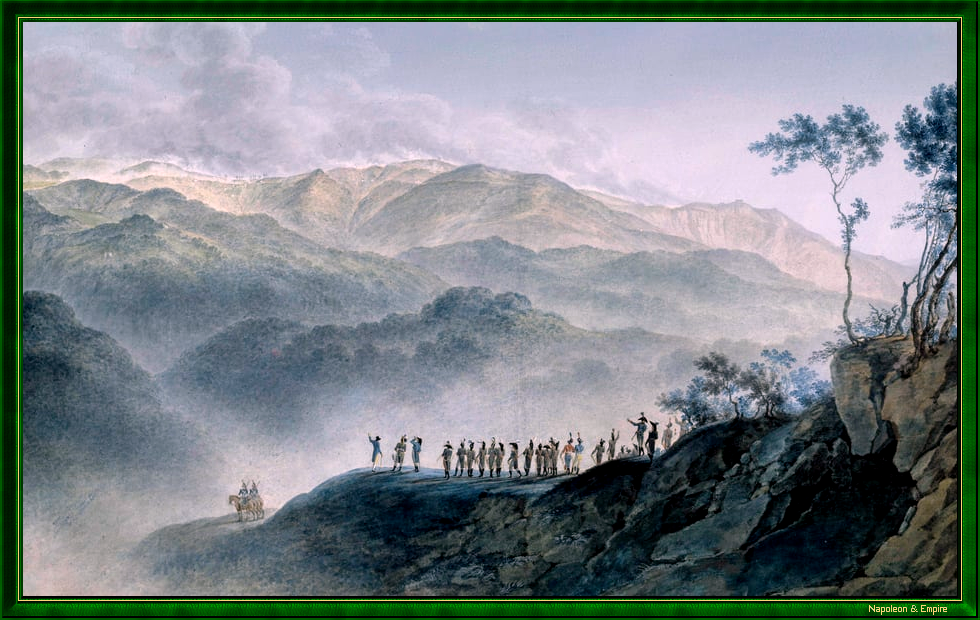

Picture - "Generals Massena and Laharpe looking at the battle from Montenotte heights". Painted by Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti (after J. Parent).

Napoleon states in his Memoirs that it was at Dego that he first noticed the future Marshal Jean Lannes.

Display the Map of the First campaign in Italy (1796-97)

Display the Map of the First campaign in Italy (1796-97)

Photos Credits

Photos by Lionel A. Bouchon.Photos by Marie-Albe Grau.

Photos by Floriane Grau.

Photos by Michèle Grau-Ghelardi.

Photos by Didier Grau.

Photos made by people outside the Napoleon & Empire association.